IT'S 1 THE BAG

Page 48

Page 49

Page 50

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

• If lorry manufacturers are to be believed, most of the road haulage industry's problems can easily be solved. Tractive units are generally available in 4x 2 and 6x2 forms; some even offer a 6x4 version. All the operator needs to do is to select his type of operation, and find well-designed, durable product to fit those particular needs.

Experienced operators will tell you that this is all guff. Each type of truck has its own advantages — and disadvantages.A 4 x2 tractor, for example, will be light, with a useful turning circle, but attracts a higher tax bill, not to mention higher tyre costs and the possibility of overloading the drive axle. A 6x4 tractor has excellent traction, but it is more complicated, heavier, and less manoeuvrable.

So is a 6x2 twin-steer the answer? Nick Downing feels it is, at least for his type of general haulage operation, except that he needs to lift the second axle on occasion to get increased traction when hauling logs out of the woods.

Most UK-specification positive twinsteers are able to dump the air in their second steering axles, but they don't lift completely clear of the ground.

This means that when the going gets really sticky, the second steering axle is still taking a small amount of the weight — and more importantly, the hardworking drive axle is not getting the benefit of the second steered axle's transfer weight as it would if there were a true lift capadty.

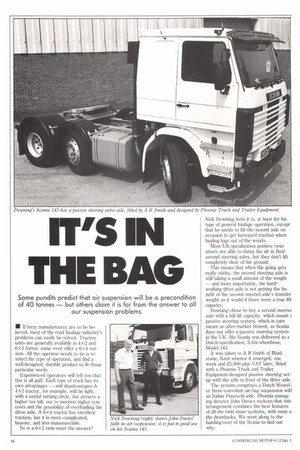

Downing chose to buy a second steered axle with a full lift capacity, which meant 2 passive steering system, which in turn meant an after-market fitment, as Scania does not offer a passive steering system in the UK. His Scania was delivered as a Dutch-specification, 3.8m-wheelbase, Model 143.

It was taken to A R Smith of Maidstone, Kent whence it emerged, one week and 25,800 plus VAT later, fitted with a Phoenix Truck and Trailer Equipment-designed passive steering setup with the axle in front of the drive axle.

The system comprises a Dutch Weweler three-convolute-air-bag suspension witl an Italian Fiaceschi axle. Phoenix managing director John Davies reckons that this arrangement combines the best features of all the twin-steer systems, with none o the drawbacks. We went along to the handing-over of the Scania to find out why. Davies has worked exclusively with air suspensions for over seven years, after a lifetime in the industry. He feels that air suspension should be simple and directacting in design, combining a decent amount of wheel travel with good braking and quick air transfer.

Armed with this philosophy, and a warehouse full of Europe's finest air suspension equipment Davies supplies a number of conversion parts to second-axle fitters, acts as an unofficial guru to the baffled and, most importantly, thinks about and designs second-axle installations.

Downing's Scalia represents the acme of Davies thoughts on passive twin-steer systems. He claims that it avoids a number of the pitfalls that he has seen some other converters and other manufacturers fall into.

Taking the Fiaceshi axle first, it is cast with a double cant to clear the propshaft and the chassis rails. Davies reckons that some twin-steers have so little wheel movement that there is a danger of axlechassis contact (and as we went to press we had two phone calls from operators complaining of similar problems with brand new manufacturer's conversions).

The problem arises mainly because the axles are almost straight, giving little more than 50mm of wheel travel before hitting the chassis. The axle retains its strength with careful attention to the curves, and it does away with the lack of wheel travel,

TRAILING ARMS

Fiachesi uses trailing arms, which feature statutory EC strops to hold the axle in case of U-bolts failure. At the end of the axle are king-pins which are mounted just in front of the stub axles.

This means that the wheel is tracking behind the king-pin the whole time, so with help from the axle damper there will be little axle shimmy, even if the wheel catches a kerb at speed.

The only time the Scania's extra axle needs to be lifted is when the going gets very sticky to give extra traction, and when reversing (this is done automatically when reverse gear is selected). The wheels will self-centre when the axle is lifted, although the rubber bushes in the track-rod ends that do the work take their time over it. Another feature of the lift device is that the air from the standard Scania drive-axle air bag is used to fill the second-steer wdebags when the wheels are lowered. This means that the load transfer to the second axle is very quick indeed, without loss of traction.

The Scania's system allows around 16° of wheel rotation on the extra axle. This, says Davies, eliminates tyre scrub. We found that the extra axle wheels continued to roll without scrub even when the Seama was turned so hard that the trailer bogie locked solid on the tarmac.

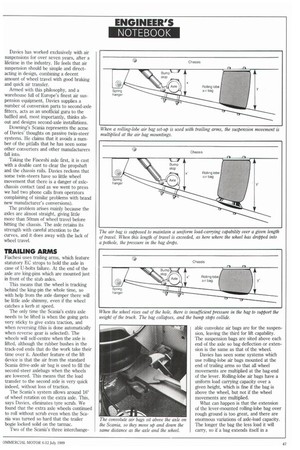

Two of the Scania's three interchange able convolute air bags are for the suspension, leaving the third for lift capability. The suspension bags are sited above each end of the axle so bag deflection or extension is the same as that of the wheel.

Davies has seen some systems which use rolling-lobe air bags mounted at the end of trailing arms so that all wheel movements are multiplied at the bag-end of the lever. Rolling-lobe air bags have a uniform load carrying capacity over a given height, which is fine if the bag is above the wheel, but not if the wheel movements are multiplied.

What can happen is that the extension of the lever-mounted rolling-lobe bag over rough ground is too great, and there are enormous variations of axle-load capacity. The longer the bag the less load it will carry, so if a bag extends itself in a pothole it will carry less load. Thus, when it gets back onto level ground, there is little load-carrying capacity available, and the suspension could bottom out.

This problem can be exacerbated by the restrictor valves in the system that are used to match drive-axle rolling-lobe bags with those on the second-steer axle. These valves are there to ensure that the extra steer axle never takes too much of the load: if it did the drive axle could spin (which is often the case), and/or the axle loadings could be illegal.

The restrictor valves prevent the free passage of air from one bag to the other, which means when the over-extended bag needs air to carry the truck's weight after it has returned to level ground, that air is slow in coming.

The convolute bags on Downing's Scania are matched to the rolling lobe bag in the standard Scania drive-axle air suspension. There is no restriction in the circuit, and Davies can map out the entire range of weights in the two axle's bags; if the drive axle is carrying two tonnes, the steer axle will carry one; if the drive axle is carrying seven tonnes, the steer axle will carry three, and so on. All this simply by selecting the right bags for the job.

As the convolute bags have a variable load carrying capacity, they give a greater roll resistance than the rolling-lobe type bag with its constant load capacity. This is because with a convolute air bag, the more the vehicle rolls, the more the bag tries to resist that roil.

The other advantage that comes from the location of the convolute bags above the axle is that the axle conversion entails little air consumption.

The legislation covering the matching of the air bags, and hence load carrying characteristics, is ambiguous. Three-axle tractive units with second-axle steering need have no compensation between the two axles, but simple add-on axles must have compensation. Passive steering systems are not specifically mentioned in the Construction and Use Regulations, but Davies does match the air bags use "because you get better braking, and no flat spots on the tyres".

STEERING AXLE

The brakes on the extra axle are full steering-axle brakes with narrow (220 x 140mm) shoes, cast-alloy shoes, one-piece back plates, needle-roller anchor pins and asbestos-free linings. "It is a narrow shoe geared to the other brake chamber sizes," says Davies, who warns that the alternative method of down-rating a wider drive-axle shoe often results in braking problems with badlyglazed drums.

He is very concerned about the braking performance on some third-axle conversions, especially the load sensing, which he feels should be simple but is often over-complicated and ineffective. The axle has a double cant so that it clears the greater wheel travel.

A pneumatic common-line load-sensing valve on the Scania means that the load is sensed on the second axle as well as the drive axle. This is in line with European conversion practice, but is not common in the UK. Davies says that he showed a European-type system at the first Type Approval for an add-on air suspension with a steel sprung drive axle in the UK, but was rebuffed. He says some people don't really understand what is happening to the brakes in such a set up.

"They don't know what the problem is," he says. "If the leading extra axle goes over a road hump, the wheels go up and let air out of the bag. When the bag drops there is no air pressure in it." Then if there is only mechanical brake sensing on the drive-axle steel suspension, "the air-suspended axle will lock up, and put a flat spot on the tyre".

Even if two rolling-lobe air bags are used on the drive axle and second steer axle, the load sensing can be inaccurate. Davies thinks that even if he used his common-line sensing system on such a braking set up there would be problems. The reason for this is that without matched air-bag characteristics, the two sets of rolling-lobe bags will have different loadcarrying characteristics at different heights, for the reasons already discussed. If the bags are at different heights over rough ground, the load will be different for each set of bags.

Common-line pressure sensing here would mean that the braking pressure would only suit one axle, with a risk of flat-spotting the tyres again.

PARTLY LOADED

Of course, this would only be where the vehicle is partly loaded, but if an airsuspended triaxle trailer has been loaded to 38 tonnes, then coupled to a three-axle tractor, then these problems can arise. What Davies is doing in part is finding out some of the problems that can occur when axle weights are increased without an overall weight increase.

He has endless stories of what he calls "nasties", most of which could be avoided by thinking clearly about the problem and applying a simple solution. The Scania was certainly a pleasant truck to drive. It didn't roll, despite its full load; the air suspension worked well, and the whole system seemed foolproof.

Davies clearly has a point. He has a lined notebook full of neat drawings and explanations; he does a lot of thinking about the subject, and it shows. He points to the mistakes other people have made. "This was all right in the early days with 'Klondike' 38-tormers," he says, "but the market has moved on to product liability now. It worries me because a whole section of the industry could suffer: one big accident, and we're all in trouble." 0 by Andrew English