FOUR-WHEEL BRAKES FOR HEAVIER VEHICLES.

Page 30

Page 31

Page 32

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Notes on Some Tests Carried Out Recently with Rubury-Alford and Alder Brakes and the Devvandre Servo Device.

THERE is no doubt 'whatever in our minds that, sooner or later—and.for the sake of safety, we hope sooner— every type of motor vehicle will be equipped with brakes acting on all wheels, except, possibly, in the case of the multi-wheeler, where it would no doubt be sufficient to brake on four wheels only.

Brakes acting only on the rear wheels present the great disadvantage that they give the minimum efficiency just when the maximum is required, and it is easy to understand why this should occur. The power of braking is necessarily limited by the adhesion between the wheel and the road. Once slip occurs between them the braking power is reduced, although, possibly, not so much as some people would be inclined to think. Now, in descending an incline, a considerable proportion of the weight of the vehicle is thrown forward upon the front wheels, and by imposing a check upon the vehicle by the rear wheels only this tendency is merely accentuated, so that the greater the amount of braking when descending hills, the more is the braking efficiency impaired and the easier it is for the rear wheels to lock. This action is so marked that whereas in the earlier days it was considered „essential when employing front-wheel brakes to let most of the power be applied to the rear wheels, now the reverse is the case, and often a considerably higher percentage of the total braking power may be applied to the front wheels.

In considering the addition of frontwheel brakes to a vehicle, it most be remembered that spreading the braking effort over four wheels does not necessarily increase the total braking power, unless friction in the connections can be reduced to a negligible quantity or the power of application considerably increased, but it would certainly not be an advance towards perfection if it were necessary to employ a servo device merely• to overcome faults caused by bad design and where a servo device is employedjust as great care should be taken in the avoidance of unnecessary friction in the connections as when the operation is solely by manual power.

There is no doubt that many makers C40

'of otherwise excellent vehicles still have a great deal to learn about braking. In few makes is consideration given to the 'effect of axle twist on the braking power; and there are still instances, where the pull on the brakes is affected by the load on the springs.

Up to a point, the more simple the gear the better. In some cases where Rubury-Alford and Alder frOnt-wheel brakes have been fitted by Clayton Wagons, Ltd., Abbey Works, Lincoln, the number of cross-shafts has been reduced from three to one, this being situ ated close to the rear wheels to allow for the radial movement of the axle and the differences in spring camber, loaded and unloaded. It is not always possible to utilize one cross-shaft only, this depending greatly •on the lay-out of the chassis and its wheelbase.

As an example of what losses can actually occur, in one instance it Was discovered that in order to transfer the line of the connections from the inside of the frame to the exterior a short shaft had been introduced which was pulled one way at the inner end by the connection ftom the pedal, and at the other end in the opposite direction by the reaction of the brake, thus forming a couple tending to turn the shaft bodily and causing a loss in efficiency of some 30 per cent.

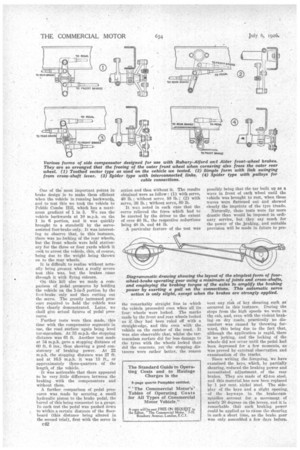

One of our illustrations shows what is perhaps the simplest and best form of brake lay-out, using a minimum of joints and cross-shafts, and this can he

used either with or without side compensation between the front and rear brakes. The principle is so to arrange the operating earns and their levers that -at the rear these are below the axle centres and at the front above them. In this way, as each axle tends to. turn under the braking torque, the braking load is amplified, this in itself giving a partial servo action.

With the ordinary form of two-wheel braking, the driver of a heavy vehicle, and particularly one capable of fairly high speeds, is at a great disadvantage as compared with the one whose vehicle is equipped with reliable four-wheel brakes. ' Even in traffic driving, where the speeds are comparatively slow, the difference is again veil marked, and it is quite a common sight to see (and hear !) vehicles rammed from the back because they, having four-wheel brakes, can pull up rapidly whilst the following two-wheeled braked vehicles cannot do so.

The Rubury-Alford and Alder frontwheel brakes, to which we have before alluded, have already proved their excellence on light classes of vehicle and are rapidly coming to the fore in connection with heavier models. One of the points in their design is that in cornering the outer front wheel is released just short of the skidding point, so that there is no fear of both wheels being held from rotating and thus causing front-wheel skid. We referred at length to this property in an article entitled "Fourwheel-brake Control," which appeared In the issue of The Commercial Motor dated January 19th.

As a result of the increasing interest in the subject, Clayton Wagons, Ltd., invited us to make some tests with these brakes as fitted to a Vulcan lorry, the total weight of which with load was 5 tons 2 cwt. 3 qrs. 14 lb., of which the Weight on the front axle absorbed 1 ton 12 ewt., including two persons, consequently that on the rear axle was 3 tons 10 cwt. 3 qrs. 14 lb. This vehicle had, in addition, a Dewandre vacuum servo device equipped with a tap so that it could be put out of action when desired. The brake gear was also so arranged that it could be used either with or without side compensation between the front and rear wheels. With out compensation, the total, leverage from the pedal to the point of contact of the cams was 72.6-1, and arranged so that it gave considerably heavier braking on the front wheels than on the rear. With the side compensators, the total leverage was 74.6-1, the braking, in this instance, being 53 per cent. on the front wheels and 47 per cent. on those at the rear, although it must, of course, be remembered that these figures cannot be arbitrarily fixed as they are affected by the proportion of the weight thrown on the wheels as previously explained, and by the braking torque on the axles.

One of the objects of the tests was to ascertain the differences obtained by using ordinary braking gear and side compensated brake gear, whilst another was to study the action and benefits obtained from the servo device, but owing to the necessity for concluding by a certain time it was not possible to make adequate trials of the gear with the serve out of action and without the brake control actually passing through the servo mechanism, but we 'hope shortly to have a further opportunity for making these.

We thought that a good locality for

the tests would be the Surrey fills, particularly as on the way we would be able to note the control of the vehicle in traffic, which was unusually interesting to us as we had not previously travelled on a comparatively heavy vehicle using the Dewandre servo. On several occasions in the thick of London traffic we observed that the servo device came into action without apparently any hesitation, and yet with a smoothness of operatiou which was really surprising.

The first test was carried out on the new Dorking road, which has a concrete surface with expansion ships about 3 ins, wide placed askew across the road. The Vulcan was run down a bill with a gradient of approximately 1 in 20 at a speed of 38.5 m.p.h. At an observed point the four-wheel 'brakes were applied and the stopping distance measured, this proving to be 101 ft., or about six lengths of the vehicle. — A very interesting action of tile . wheels are here observed. As they locked at every expansion strip and were released immediately after it, the locking and releasing causing such an abrasive action on the tyres that powdered rubber was left in front of each strip. The brakes were, in this instance, non-compensated. Without alteration, the vehicle was then tried on a level tarmacadam road, and the following results obtained: at 22 m.p.h. the stopping distance was 26 ft., with wheels locked; at 16.5 m.p.h., the stopping distance was 15 ft. 6 ins., with no locking of wheels, and at 11 m.p.h. the stopping distance was 13 ft.

Sonic of these figures were not so good as had been obtained previously, and, upon investigation, it was discovered that the Woodruff keys holding the operating levers to the camshafts of the rear brakes had partially .sheared. The slack was taken up in the hope that they would last out the test, and a continuation was made again by running on a level tar-macadam road, and the following results obtained: 35 m.p.h., stopping distance 73 ft.; 28.5 m.p.h., stopping distance 47 ft.; 27.5 m.p.h., stopping distance 39 ft.; 11 m.p.h., stopping.distance 7 ft.

One of the most important points in brake design is to make them efficient when the vehicle is running backwards, and to test this we took the vehicle to Pebble Combo Hill, which has a maximum gradient of 1 in 5. We ran the vehicle backwards at 10 m.p.h. on the 1 in 6 portion, and it was quickly brought to a standstill by the servoassisted foot-brake only. It was interesting to observe that, in this instance, there was no lockino.' of the rear wheels, but the front wheels were held stationary for the three or four yards which it look to arrest the vehicle, this, of course, being due to the weight being thrown on to the rear wheels.

It is difficult to realize without actually being present what a really severe test this was, but the brakes came through it with flying colours.

On this hill also we made a comparison of pedal pressures by holding the vehicle on the 1-in-5 portion by the ft,-it-brake only and then cutting out the servo. The greatly increased pressure required to hold the vehicle was then clearly demonstrated. Later, we shall give actual figures of pedal pressures.

Further tests were then made, this time with the compensator segments in use, the road surface again being level tar-macadam. At 33 m.p.h. the stopping distance was 61. ft. Another test made at 34 m.p.h. gave a stopping distance of 60 ft. 6 ins., thus showing a good consistency of braking power. At 22 m.p.h. the stopping distance was 27 ft. and at 16.5 m.p.h. it was 13 ft., or approximately three-quarters of the length. of the vehicle. It was noticeable that there appeared to be very little difference between the braking with the compensators and without them.

A further comparison of pedal pressures was made by securing a small hydraulic piston to the brake pedal, the 1-art-el of this being connected to a gauge. In each test the pedal was pushed down to within a certain distance of the floorboard (this distance being altered in the second trial), first with the servo in c42 action and then without it. The results obtained were as follow : (1) with servo, 40 lb. ; without servo, 88 lb.; (2) with servo, 36 lb.; without servo, 80 lb. It wal noted in each case that the -servo relieved the force which had to be exerted by the driver to the extent of over 40 lb., the respective reductions being 48 lb. and 44 lb.

A particular feature of the test was the remarkably straight line in which the vehicle proceeded even when all its four wheels were locked. The marks Inaae by the front and rear wheels looked as if they had been ruled oft with a straight-edge, and this even with the vehicle on the camber of the road. It was also observable that, whilst the tarmacadam surface did far less damage to the tyres with the wheels locked than did the concrete, yet the stopping distances were rather better, the reason possibly being that the tar built up as a ware in front of each wheel until the ehiele was brought to rest, when these waves were flattened out and showed clearly the imprints of the tyre treads. Naturally, these tests were far more drastic than would be imposed in ordinary service, but they say much for the power of the _braking, and suitable provision will be made in future to pre

vent any risk of key shearing such as. occurred in this instance. During the stops from the high speeds we were in the cab, and, even with the violent braking on dry roads, practically no discomfort was caused by 'throwing forward, this being due to the fact that, although the application is rapid, there is no jerking, and the locking of the wheels did not occur until the pedal had been depressed for a few moments, as was proved by external observation and examination of the tracks.

Since writing the foregoing, we have examined the keys, which, by partially shearing, reduced the braking power and necessitated adjustment, of the rear brakes. They are made of 42-ton steel, and this material has now been replaced by. 1 per cent, nickel steel. The sideplay of the keys and a slight opening.. of the keyways in the brake-cam spindles account for a movement of Alea.rly 20 degrees on the levers, and it is remarkable that such bralang power could be applied as to cause the shearing in such a short time, as the brake gear was only assembled a few days before.