rhe county councils and co-ordination

Page 52

Page 53

Page 54

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Ls now about nine months since the inty Council began to exercise the rers acquired under Section 203 of 1972 Local Government Act. These lers are quite explicit; each county ncil is given "the duty" to promote provision of a co-ordinated and :lent system of public passenger tsport to meet the needs of the nty and, for that purpose to promote co-ordination, amalgamation and rganization of road passenger trans: undertakings in the county as Dar to the county council to be rable.

he metropolitan county councils the Passenger Transport Execu; to exercise the responsibilities of ion 203, reinforced of course by wider powers under the 1968 isport Act. In the shire counties e has been no benefit of a profesal executive directed towards public sport. Fq.ced with what amounts to rtually new area of concern, the nty Councils have had to deter their own organizational oach. What has been done differs one county to another. In the first the departmental structures are dentical. Some authorities have set directorate of transportation and fling and clearly public transport -eadily form part of such a depart's responsibilities. In the majority :ases . though, more traditional rtmental structures have been ned. A number of councils have recognized their new powers by appointing a Public Transport Coordination Officer, but his status, duties, responsibilities and authority can vary widely according to which county council employs him. In many cases he is responsible to the county surveyor, but in others he reports to the county planning officer and there are some attached to the county secretary or located within the chief executive's office. Furthermore there is a fair scattering of skills. Whilst in several cases men have been drawn from bus or rail management, there are a number of transportation engineers, town planners, etc, who have been recruited to these posts. Indeed it is interesting that while some councils have appointed at least one person from the public transport industry, others have not done so.

It is also noticeable that the committee structures and political organizations to deal with public transport matters differ widely between the various councils.

Co-ordination task All this variety represents not only differing attitudes towards a county council's role of co-ordinating public transport but also the widely diverse problems that public transport presents for each of the councils.

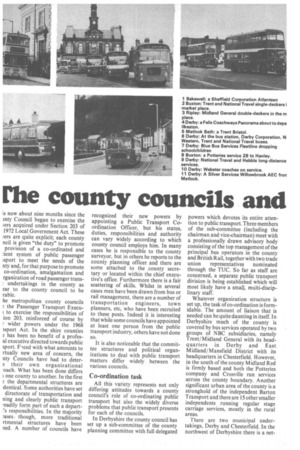

In Derbyshire the county council has set up a sub-committee of the county planning committee with full delegated powers which devotes its entire attention to public transport. Three members of the sub-committee (including the chairman and vice-chairman) meet with a professionally drawn advisory body consisting of the top management of the principal bus operators in the county and British Rail, together with twO trade union representatives nominated through the TUC. So far as staff are concerned, a separate public transport division is being established which will most likely have a smals1, multi-disciplinary staff.

Whatever organization structure is set up, the task of co-ordination is formidable. The amount of liaison that is needed can be quite daunting in itself. In Derbyshire much of the county is covered by bus services operated by two groups of NBC subsidiaries, namely Trent/ Midland General with its headquarters in Derby and East Midland/Mansfield District with its headquarters in Chesterfield. However, in the south of the county Midland Red is firmly based and both the Potteries company and Crosville run services across the county boundary. Another significant urban area of the county is a stronghold of the independent Barton Transport and there are 15 other smaller independents running regular stage carriage services, mostly in the rural areas.

There are two municipal undertakings, Derby and Chesterfield. In the northwest of Derbyshire there is a net work of services operated by Greater Manchester PTE, and the South Yorkshire PTE run services across the northern boundary of the county. In all, some 25 individual concerns providing bus services. To these may be added two divisions of British Rail. Also to this list there should be added the profusion of bus and coach companies who operate school and works contracts.

However, the operators are not the only people with whom liaison takes place. There are nine district councils in Derbyshire, and apart from the two who operate their own bus undertakings there is among the others a very keen interest in local bus services. The district councils want to be consulted and to be able to put up their own ideas. The Peak Park Planning Board also has certain powers and interests both in bus and rail services. Even parish councils are beginning to write to county headquarters with their particular problems on the local bus and train services. Also, in a county like Derbyshire little can be achieved without a very close working relationshipvith neighbouring county councils — four non-metropolitan councils abut Derbyshire.

The list does not end with the operators and the local authorities; links also exist with the Transport Users Consultative Committees and other consumer bodies. Finally, in Derbyshire's case the county falls within four Traffic Commissioners' areas. Altogether nearly 50 different bodies are involved in the county's interest in public transport.

In many respects the new powers of the county councils could not have come at a worse time. Inevitably they are seen in some quarters as an extra commitment which is going to take up resources at a time when local government spending is restricted to a level which makes it almost impossible to maintain existing services, let alone venture into new fields. The effect of inflation is having an equally marked impact on the viability of bus services. There is a real danger that the role of the county councils will be seen merely as a means of providing subsidies for an ever-increasing number of loss-making services.

Staggering claims

Many County Councils are naturally reluctant to see services withdrawn or even reduced to any extent before they have had an opportunity to consider their new role objectively and at least arrive at some interim policies. The contrast in terms of financial support is nonetheless quite staggering. In Derbyshire the total grants estimated for rural bus subsidies in the current financial year amount to £12,000 of which the County Council pays only £3,000. The initial claims for supporting rural services next year have alrady reached £430,000, and to this amount there can be added further substantial claims for other loss-making services. This has naturally given rise to a great deal of questioning as to why the sums ha, become so large so quickly. Faced wi similar claims some county councils a fearful that all that will happen is th each year they will pour their scar funds into escalating subsidies witho making any progress towari improving public transport.

However, one National B subsidiary is already making it clear th without aid from central governthei measures will have to be taken to restc financial viability. Cuts in services have to be made on the basis of level cost and thus, unless the county cou cils do provide substantial financial su port, major changes are foreseen in t scale of peak period operations, esr cially in respect of services that mair carry schoolchildren.

Both British Rail and the h operators have indicated a willingni to try new services and new id( provided that the county count underwrite the costs. While this perfectly justifiable attitude there i; danger that the initiative of the tra port operators to introduce their a innovations and experiments could IA be lost. At times it is difficult to kn whether the councils will be able to ex cise any effective role under th Section 203 powers without a finam involvement. The powers amalgamate and re-organize bus und takings are explicitly stated, but remains to be seen whether the word: the Act have any effective force. he independent operators tend to v the 'county councils with some ;e of suspicion and the general ression is that, while grants are led, interference in any form is ainly not. The PTEs of course esseny work to the policies of their metrotan county councils and generally view has developed that where ices cross their county boundary I it is up to the shire counties to rmine what is to be done in respect le service provided and the fares to charged. Quite opposite policies d be passed in respect of the same ice on either side of a county -Wary!

le of the most difficult problems to ye is the interface between muniand company operations. As a equence of both the recent revision earlier revisions to council bound,' residents of the same borough can tying totally different fares accordD whether they are lucky enough or o be served by the local council's In some cases company fares are st double those of the municipal rtaking. This may reflect in part the support provided by the district cils towards the costs of their own services; a support from which , ratepayers do not benefit. Howthis is by no means the only factor t is an issue which can highlight the ing objectives and attitudes of the kinds of operator. By contrast, is the problem of the municipal ;ervices that operate into neighng district council areas at the ise of the parent council rates. The rural areas of course present their own particular problems, and at times it is difficult to know where the public transport co-ordination task sfarts or ends. Many of the issues relate to the ability of people to reach doctors' surgeries, clinics, hospitals, the post office etc. Conventional bus services are not always the answer and the problem can lead into the whole realm of social service facilities, hospital transport and car schemes, most of which may not be strictly regarded as public transport.

In Derbyshire all the bus operators have highlighted the carriage of schoolchildren as a major issue. In the rural and urban areas alike it is the school movement which determines the peak period operation and the size of fleet that is maintained. In particular, the manner in which school contract buses are organized can have vital repercussions on stage carriage services. Also if in the future emphasis is to be placed on peak period costs then school buses will prove to be much more expensive than they are now. The county councils cannot afford to ignore this issue if co-ordination is to be realistically pursued.

The main aim of Section 203 of the 1972 Local Government Act was to bring some order into transportation as a whole, to ensure that a balanced approach was achieved whereby both public transport and highways could be approached on equal terms. The abolition of the old grant systems and the introduction of the yearly submission of a Transport Plan and Programme has provided the basic tool for the job. How it is used will depend perhaps on the degree to which the county councils have the will to give priority to public transport requirements.

Certainly it seems likely that current and immediate issues are to dominate the overall task of co-ordination. The, workload to be handled will not be readily controlled by the county councils as such issues are likely to be raised not only by the public transport operators but by the district Councils, parish councils, pressure groups, consumer groups and members of the public. The manner in which the councils are able to deal with these matters may well set the context in which longer term policies can be set in the county structure plans.

It has to be recognized that the bus business in particular is a labourintensive industry. The policies of county councils can only be carried out if the manpower is available and against a background of favourable industrial agreements. One of the dangers is that county counciis will not be adequately aware of the way in which buses are scheduled and run and the constraints that management must work within.

In the final analysis the question will he, does the new way provide better public transport for the community and better value for money? The difficulties of making the legislation effective are all too apparent; what is initially needed is a sense of partnership and purpose with a common will to succeed on the part of both the local authorities and the managements of the bus and rail undertakings. If this is secured then progress can be made.