Ford DT1400 20-ton-gross 6 x 4 tipper

Page 87

Page 88

Page 89

Page 90

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

by A. J. P. Wilding,

IVIIMechE, MIRTE THERE was a time when a tipper was produced in the most basic form—minimum specification, minimum standards for the driver and minimum price. But not so now. Much more attention is paid by manufacturers to the design of chassis offered as the basis for tippers, cab-interior quality is not always pared down because "the driver does not go as far from base as a long-distance man" and operators appear more willing to pay a higher price for a tipper that should do its job that much better.

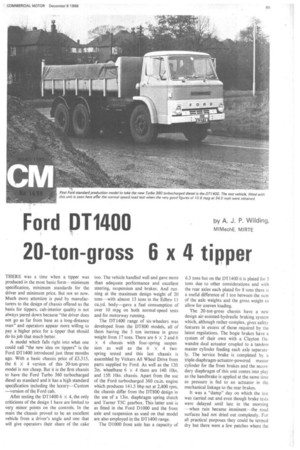

A model which falls right into what one could call "the new idea on tippers" is the Ford DT1400 introduced just three months ago. With a basic chassis price of £3,315, the 6 x 4 version of this 20-ton-gross model is not cheap. But it is the first chassis to have the Ford Turbo 360 turbocharged diesel as standard and it has a high standard specification including the luxury—Custom —version of the Ford cab.

After testing the DT1400 6 x 4, the only criticisms of the design I have are limited to very Minor points on the controls. In the main the chassis proved to be an excellent vehicle from a driver's angle and one that will give operators their share of the cake too. The vehicle handled well and gave more than adequate performance and excellent steering, suspension and brakes. And running at the maximum design weight of 20 tons—with almost 13 tins in the Edbro 11 cu.yd. body—gave a fuel consumption of over 10 mpg on both normal-speed tests and for motorway running.

The DT1400 range of six-wheelers was developed from the DT800 models, all of them having the 3 ton increase in gross weight from 17 tons. There are 6 X 2 and 6 X 4 chassis with four-spring suspension as well as the 6 X 4 twospring tested and this last chassis is assembled by Vickers All Wheel Drive from parts supplied by Ford. As well as the 1211 2in. wheelbase 6 x 4 there are 1411 10in. and 15ft 10in. chassis. Apart from the use of the Ford turbocharged 360 cu.in. engine which produces 141.5 bhp net at 2,400 rpm, the chassis differ from the DT800 design in the use of a 13in. diaphragm spring clutch and Turner T5C gearbox. This latter unit is as fitted in the Ford D1000 and the front axle and suspension as used on that model are also employed in the DT1400 range.

The D1000 front axle has a capacity of 6.3 tons but on the DT1400 it is plated for 5 tons due to other considerations and with the rear axles each plated for 8 tons there is a useful difference of 1 ton between the sum of the axle weights and the gross weight to allow for uneven loading.

The 20-ton-gross chassis have a new design air-assisted-hydraulic braking system which, although rather complex, gives safety features in excess of those required by the latest regulations. The bogie brakes have a system of their own with a Clayton Dewandre dual actuator coupled to a tandem master cylinder feeding each axle separately. The service brake is completed by a triple-diaphragm-actuator-powered master cylinder for the front brakes and the secondary diaphragm of this unit comes into play as the handbrake is applied at the same time as pressure is fed to an actuator in the mechanical linkage to the rear brakes.

It was a "damp" day on which the test was carried out and even though brake tests were delayed until late in the morning —when rain became imminent—the road surfaces had not dried out completely. For all practical purposes they could be termed dry but there were a few patches where the tarmac was still slightly damp. This was shown up by inconsistent locking of the rear wheels; on one stop the offside rear locked for 23ft, on another maximum pressure stop the wheels on the offside forward-axle locked for 12ft and on another the nearside forward axle wheels locked for oft. On only one stop did all the bogie wheels lock—for about 10ft—and the road was clearly wet• at that point. There were no marks at all from the front wheels which shows that the condition did not have any serious effect on the figures obtained.

The stopping distances on my test were equal or better to figures quoted by Ford for its dryiroad tests and they were well up to the standard expected. A little more effort at the front wheels would seem to be possible without any unacceptable side effects and this would give even shorter stopping distances. Maximum decelerations as recorded by Tapley meter were 76 from 20 mph and 69 per cent from 30 mph and the handbrake—secondary system—gave a retardation of 42 per cent with no wheel locking.

Acceleration tests produced very good figures for through-the-gear runs. On these, the vehicle was started in second gear with low ratio in the rear axles engaged and each main ratio split in the progression through the gearbox. At first, the axle-change worked perfectly but with the heavy work on the transmission during the acceleration runs, the standard reduced and even though similar techniques were employed there were occasional mis-changes at the axles. These required repeat tests to be made to get the figures quoted in the table but on normal driving, the change mechanism for the two-speed axles worked well.

Direct-drive acceleration tests were made first of all with the low-9.04 to 1—ratio in the axles engaged as this is the normal practice. But as maximum speed in fifth /low was only 37 mph, the tests were repeated in fifth /high (6.5 to I). Even though the engine speed in the latter case was fractionally below idling speed at IQ mph, the vehicle pulled away reasonably. In the circumstances the times were quite good. They Were better than I anticipated as one does not expect a turbocharged engine to do very much at such low engine speeds. It was very noticeable on these tests that after about 1,200 rpm the power build-up was quite dramatic. This confirmed that the best normal driving practice with this vehicle—and for that matter for any with a turbocharged engine—is to keep the engine rpm near the top end of the scale. In the case of the Ford found it best to keep the engine in the band above 1,800 rpm for maximum performance.

Speeds in the gears were checked in between the acceleration tests and the maxima were 4, 11,20, 31 and 37 with low axle ratios engaged and 6, 16, 28, 42 and 50 in high. It will be seen from these maximum speeds that the proper gear change sequence when splitting each ratio is to engage low then high axle ratio with successive main box ratios up to 4th /low. The next highest gear is then 5th /low followed by 4th /high and 5th /high. This sequence at the top end of the box works quite well in practice in that the majority of changes when on the run can be made without relying on a full knowledge of the particular technique required to make an axle-ratio change.

Fuel consumptions were checked on the usual six-mile out-and-return stretch of A6 south of Luton and the 16.1 mile return run between A6 and A4147 junctions of Ml. The figures were very good for a vehicle grossing 20 tons particularly with the low axle ratios as employed on the test vehicle. The motorway test included about 0.7 mile of normal road at the southern end used to make the turn to get back on the motorway. So it will be seen that to average 42.8 mph, the six-wheeler was close to its maximum of 50 mph for most of the journey. Surprisingly, this part of MI had relatively light traffic at the time of the test and there were no hold-ups due to baulking by other vehicles. Minimum speed on the southern run was 35 mph on the hill just after A5, and 31 mph on the gradient just after the same junction on the northern leg. The only gear change was a drop to 4th/high for the gradient after A5 on the northern stretch and on downhill gradients the speed went up to 54 mph on overrun.

Results of the hill-performance checks can be seen in the Ole and here the Ford also did well, particularly on the fade check when the brake efficiency only dropped three points—to 73 per cent—after this fairly severe test.

On most vehicles with five-speed transmission, first is normally rather awkward to engage being usually intended for use only in special circumstances—as a crawler gear for instance. In common with others, first on the Turner is over to the extreme left of the gate and then back. I found engagement of this ratio fairly easy on the hill climb although there is constant mesh as against syncromesh for the rest of the box. But disengagement and selection of second while still climbing was less easy; extra

effort was needed to disengage and in the process I found it easy to "clout" the reverse gears and then difficult to find the slot for second. This will normally mean that a driver will hang on to first longer than absolutely necessary to ensure making a good change into second but the same must happen to most boxes with the same layout.

One of the more interesting aspects of this test is that it is the first of a standard British vehicle fitted with a turbocharged engine. This type of engine is going to become much more common in this country in the future and the results prove that there are definite advantages in extra performance without worsening of fuel consumption. There is also the advantage of a lower noise level than would be the case for a naturally-aspirated diesel of comparable output. The Ford had a very low level of noise in the cab and normal conversation was hardly affected. But then the Ford cab is a well designed unit and like other chassis from the same company that I have tested has had a lot of attention paid to insulation.

Ford also gives a lot of importance to driver comfort and easy control and as with other Ford heavies, the 6 x 4 gets high marks in these respects. The driver's seat has a suspension-type support which eases out all of the bumps and any vibration due to rough road surfaces although the suspension of the chassis is well designed and no jarring shocks reached the cab support.

The power steering on the chassis was found to be a very good design with light action and still enough "feel", but there was a fault in that the steering occasionally "stuck" on a full right-hand lock and the wheel needed a push round before the castor action would take over and bring the steering back. Adjustment of stops may have helped to cure this as the right-hand turning circle was 2.6ft less than the left-hand.

Like most heavy-truck synchromesh gearboxes there was some heaviness in engaging the gears and the synchromesh could be beaten on 2nd and 3rd. When a lot of gear changing was being carried out in the acceleration tests, roughness of the gearchange knob was notable; there were also some rather sharp edges on the bracket holding the axle-change knob.

The test vehicle had the optional air windscreen wipers and the dash-mounted knob controlling these also had a sharp edge which was unfortunate because a considerable amount of effort and a tight grip was needed to turn the knob in an anticlockwise direction to bring the wipers to the "park" position.

Handbrake control

On previous Fords that I have tested I have not been happy with the handbrake control and the DT1400 has the single-pull umbrella type unit currently used by Ford on its heavy models. Application was easy but I found it difficult to release the handbrake completely without three or four attempts at it. A special technique seemed to be required and although I felt I was getting there at times I never really mastered it in the time I was with the vehicle. I was told after the test that some adjustment had been made but this may have been due to my abuse of the mechanism.

The brakes of the DT1400 must give the driver confidence. They are very responsive and the efficiency is equally good and the hydraulically operated clutch was reasonably light. The test vehicle had the optional "Western" mirrors and these gave a good view to the rear although I would not say the nearside view was perfect; I like to see the bottom of the rear tyres in that corn

ponent. It struck me once again that British manufacturers are "stuck on" flat glasses for mirrors but I have yet to find a driver who does not prefer convex. Well-designed mirrors of this type would do as good a job as Ford's Western-type without all the brackets needed.

The driver could not wish for a better standard of cab interior than that given by the Ford Custom design but enough praise has been given it in previous road test reports of Fords. The cab is well instrumented and all controls are within easy reach. Access is easy although I would still like a grab handle on the driver's forward door pillar.

Time did not allow for the Ford to be put through its paces in off-the-road conditions but I would not anticipate any problems with the vehicle particularly as the double drive rear bogie has differential lock. When restarts were made on the 1 in 6.5 gradient at Bison, the road surface was greasy but there was no sign of any loss of adhesion that would have made using the differential lock necessary.

As already stated the basic price of the Ford DT1400 as tested is £3,315. Options fitted to the test chassis included 10.00-20 tyres (£32), air operated wipers (£8), Western mirrors (£10) and tachometer (£10). With the cost of the two-speed axles at £135 this brought the list price of the vehicle tested to £3,510.