COMING DOWN THE MOUNTAIN

Page 30

Page 32

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

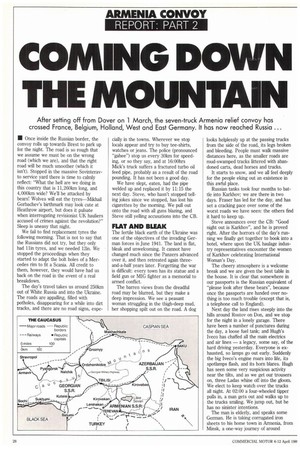

After setting off from Dover on 1 March, the seven-truck Armenia relief convoy has crossed France, Belgium, Holland, West and East Germany. It has now reached Russia ...

• Once inside the Russian border, the convoy rolls up towards Brest to park up for the night. The road is so rough that we assume we must be on the wrong road (which we are), and that the right road will be much smoother (which it isn't). Stopped in the massive Sovinteravto service yard there is time to calmly reflect: "What the hell are we doing in this country that is 11,260km long, and 4,000km wide? We'll be attacked by bears! Wolves will eat the tyres—Mikhail Gorbachev's birthmark may look cute at Heathrow airport, but does it pulsate when interrogating revisionist UK hauliers accused of crimes against the revolution?" Sleep is uneasy that night.

We fail to find replacement tyres the following morning. That is not to say that the Russians did not try, but they only had 11in tyres, and we needed 12in. We stopped the proceedings when they started to adapt the bolt holes of a Mercedes rim to fit a Scania. All credit to them, however, they would have had us back on the road in the event of a real breakdown.

The day's travel takes us around 250krn out of White Russia and into the Ukraine. The roads are appalling, filled with potholes, disappearing for a while into dirt tracks, and there are no road signs, espe cially in the towns. Wherever we stop locals appear and try to buy tee-shirts, watches or jeans. The police (pronounced "gahee") stop us every 30km for speeding, or so they say, and at 16:00hrs Mick's truck suffers a fractured turbo oil feed pipe, probably as a result of the road pounding. It has not been a good day.

We have slept, eaten, had the pipe welded up and replaced it by 11:15 the next day. Steve, who hasn't stopped telling jokes since we stopped, has lost his cigarettes by the morning. We pull out onto the road with all guns blazing, and Steve still yelling accusations into the CB.

FIAT AND BLEAK

The fertile black earth of the Ukraine was one of the objectives of the invading German forces in June 1941. The land is flat, bleak and unwelcoming. It cannot have changed much since the Panzers advanced over it, and then retreated again threeand-a-half years later. Forgetting the war is difficult: every town has its statue and a field gun or MIG fighter as a memorial to armed conflict.

The barren views from the dreadful road may be blurred, but they make a deep impression. We see a peasant woman struggling in the thigh-deep mud, her shopping spilt out on the road. A dog looks helplessly up at the passing trucks from the side of the road,, its legs broken and bleeding. People must walk massive distances here, as the smaller roads are mud-swamped tracks littered with abandoned carts, dead horses and trucks.

It starts to snow, and we all feel deeply for the people eking out an existence in this awful place.

Russian tanks took four months to battle into Karkhov; we are there in two days. Fraser has led for the day, and has set a cracking pace over some of the worst roads we have seen: the others find it hard to keep up.

Steve announces over the CB: "Good night out is Karkhov", and he is proved right. After the horrors of the day's running we finally get together to book into a hotel, where upon the UK haulage industry representatives encounter the women of Karkhov celebrating International Woman's Day.

The cheery atmosphere is a welcome break and we are given the best table in the house. It is clear that somewhere in our passports is the Russian equivalent of "please look after these bears", because once the passports are handed over nothing is too much trouble (except that is, a telephone call to England).

Next day the land rises steeply into the hills around Rostov on Don, and we stop for the night in a lonely garage. There have been a number of punctures during the day, a loose fuel tank; and Hugh's Iveco has chaffed all the main electrics and air lines — a legacy, some say, of the hard driving yesterday. Everyone is exhausted, so lamps go out early. Suddenly the big Iveco's engine roars into life, its spotlamps flash, and its horn blares. Hugh has seen some very suspicious activity near the tilts, and as we get our trousers on, three Ladas whine off into the gloom. We elect to keep watch over the trucks all night. At 02:00 a four-wheeled tipper pulls in, a man gets out and walks up to the trucks smiling. We jump out, but he has no sinister intentions.

The man is elderly, and speaks some German. He is taking corrugated iron sheets to his home town in Armenia, from Minsk, a one-way journey of around 3,300km, which he is doing in three hits. His eyes are full of tears when he tells us of the devastation, and so are ours when he clasps our hands in thanks. We look at the pristine truck from which he works. "Primitive?" he asks, and it is. We give him food and cigarettes; he gives us information on the road ahead. "Gangsters have guns here," is his less-thanreassuring parting shot.

The run down from Rostov to the Black Sea port of Novorossijsk is marked by lousy diesel fuel, blocked fuel filters, flat countryside and the appearance of "nodding donkey" oil-well pumps as we near the coast. By now the trucks are creating quite a stir when they get to town. Trying to sleep is a bit like catching 40 winks in the pits at Silverstone, so noisy are the stopping cars and shouting. We get totally lost in Krasnodar, someone sees a coffin in the road, Mark loses a mudguard, we discover coffee and vodka is not a bad drink, and Steve loses his cigarettes again. At Novorossijsk the hills start.

On the map, the road between the suburbs of Novarossijsk, and Sochi looks dead straight. In fact, it tortuously climbs each peak of the Caucasus Mountains with blind turns, poor surfaces and suicidal drivers. On the second day of this it rains: Steve, with his slick tyres, and Peter, in a 6x 2 tractive unit, have real problems. Trying to avoid high revs and wheelspin, Peter comes to a halt on one hill — only by dumping the air in the Dafs second steering axle and carefully letting in the clutch does he make slipping, scrabbling progress up the hill.

By this time no one had had a shower for four days, and morale is starting to slip. We seem to be carefully missing a hotel each night when we stop. Night driving is almost impossible, and the convoy is making around 350km per day. Mark is getting particularly familiar with the Scania's cab tilt mechanism, changing fuel filters, pumps, bleeding diesel, and generally trying to find out where all his turbocharged, intercooled power has gone. Mick decides we will stop in Tbilisi.

LANDSLIP DAMAGE

The Georgian military road runs through a gorge between the major and the lesser Caucasus. Landslip damage is very bad, and the trucks' passage makes the road edges crack and fall several hundred metres into the gorge. It feels good when we finally make it into Tbilisi, and even better when we are directed to the best hotel in the capital of Georgia. Imagine seven Georgian hauliers parking up in Hyde Park and changing their fuel filters there before adjourning for a night in the Dorchester, and you'll be somewhere near the truth.

Monday is Yerevan day, We have showered (no bath plugs in Russia), eaten (more beetroot soup), and are ready to dodge the pigs, sheep and cows on the road between Tbilisi and the capital of Armenia. We fill up with fuel at the dirtiest garage yet, where the savvy attendant wants everything bar the truck's gearboxes as a "souvenir", and start towards the lesser Caucasus.

The road goes through Azerbaijan and on in to Armenia. The tension that exists between these two republics is well known, and is the first internal Soviet border we have seen with guards, guns and tanks. It is now very warm and, in shirtsleeves, we start to climb the Diligan pass up to Lake Servan, one of the highest mountain lakes in the world.

The climb starts at 150m and ends at 2,134m, with over 40 hairpin bends along the way from the mountain valley to the snow line. It starts with a flat fast run higher and higher, and then the hairpins start. Engines roar and a glance backward reveals the wide valley; look forward and there are snow-covered peaks. Never mind the Scania splitter or the ZF detent, just get that gear! The drivers are shouting encouragement to their steeds, water temperatures rise, the turbos are glowing red. One hairpin leads to another, tyres scrabble for grip, two trucks heel over onto two wheels and slam down on all four exiting the corner. . .

Suddenly its over. We are at the top. Our ears pop as we look at the breathtaking view ahead. Lake Servan is frozen and looks like a white blanket on the ground; snowy peaks merge with overcast sky.

After a short break we make our way down the other side of the mountain into Yerevan, passing through shanty towns where men sit drinking and smoking while their women struggle under monstrous loads. The road slopes down sharply now, and the people are obviously well aware what the convoy is all about. Oncoming truck drivers climb half out of their cabs to salute us, horns hoot, and bystanders wave. The convoy shatters the mountain silence with racing engines, air brakes and clattering exhausts.

On the outskirts of Yerevan a friendly local picks us up and leads us to the central Lenin Square. The trucks battle through the hysterical driving of the ring road and into Lenin Square to park along side Red Army tanks. People ignore the protesting police and soldiers, to come over and greet us.

It would be nice to leave the trucks there under the expressionless statue of Lenin, engines ticking as they cool, and small drops of oil appearing on the hallowed tarmac. Drivers clutching mugs of tea, smoking, telling their own story to anyone who will listen. In fact, there is a sour twist to the story the following morning, when the drivers are impatient to tip their loads and be on their way. A Red Cross worker joins us for the meal, and tells us bluntly that the whole trip has been a waste of time. "The people in the villages are throwing our clothes away; we are burying drugs because we cannot use them before they are out of date," he says, adding; "Back in December the International Red Cross were saying: 'Don't send any more stuff, we need money."

SUPPLY COCK-UPS

It seems the Red Cross will have to beg people to store our goods. We go over to the main office to see what's going on. The place is strewn with old telex messages telling of major supply cock-ups before Christmas last year. "We had Swiss rescue dogs fighting British rescue dogs — it was chaos," one man says.

When the consignees arrive they direct the trucks to a seemingly derelict but functioning rubber factory. As the first truck (Steve's) starts to be unloaded, a deputation from the Armenian Committee for Cultural Relations with Armenians Abroad, arrives. The unloaded blankets have barely touched the floor before they are hurriedly loaded aboard four-wheel trucks and on their way to the earthquake area. Hugh's truck, containing toys and food, is sent off to unload at a hospital. It appears we are wanted after all.

The loads were needed and the Red Cross was wrong. On arrival back in England the Aid Armenia charity was furious. It had arranged for the loads to be relevent to the needs of the area, and this was not the first run up it had had with the International Red Cross.

The convoy achieved its 5,3341on objective proving that modern Western trucks can survive the rigours of a run to Armenia, and more pertinently to the industrial areas of South East Ukraine. Eurotrux hopes to run driver-accompanied freight down to the Ukraine and beyond.

As for the drivers, they all claimed it was just another job; but their obvious disappointment when told the convoy was not needed belied this cool facade. It makes a change to report trucks bringing immediate, tangible benefits to people in desperate need. The drivers displayed a level of skill, initiative and downright guts that was far, far above the call of duty. The run has left this reporter with memories that will last a lifetime.

Dby Andrew English