PAUNICIPAI

Page 68

Page 69

Page 70

Page 71

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

MEDIOCRITII

• When Leyland Daf announced a new set of engines for its 400 Series vans (we mustn't call them Sherpas anymore), there was never any doubt that we would get both the naturally-aspirated and the turbocharged versions for test. The most impressive vehicle in the range, and the first on the test fleet, was the blown longwheelbase, high-roof van with rear air suspension. We liked its healthy power output and good handling (CM 22-28 June). With more attention to the details we felt that Leyland Daf had a winner on their hands.

But what of its humble stablemates — the unblown, steel-suspended, cooking members of the 400 Series family? You know, the sort of van you regularly see at the side of a country road, engaged in essential maintenance with a brace of somnolent council workers. The unglamourous version; or to the more uncharit )le, the boring one. Well here it is. This eek's roadtest is of the naturally;pirated, long-wheelbase chassis-cab veron of the Leyland Daf 400 Series, and it well to remember that this is probably le most important vehicle in the range. This, after all, is the vehicle that will ll in the largest numbers, to British Rail aintenance gangs, to local authorities, to ilders: in short, to owners who decide tat they would rather have the lower fuel Hs and slower journeys than the power id prestige of the turbo version.

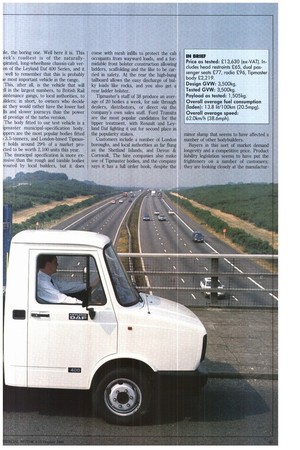

The body fitted to our test vehicle is a ipmaster municipal-specification body. ippers are the most popular bodies fitted 3.5-tonners, and London-based TipmasT holds around 29% of a market procted to be worth 2,100 units this year. The municipal specification is more exnisive than the rough and tumble bodies voured by local builders, but it does come with mesh infills to protect the cab occupants from wayward loads, and a formidable front bolster construction allowing ladders, scaffolding and the like to be carried in safety. At the rear the high-hung tailboard allows the easy discharge of bulky loads like rocks, and you also get a rear ladder bolster.

Tipmaster's staff of 38 produce an average of 20 bodies a week, for sale through dealers, distributors, or direct via the company's own sales staff. Ford Transits are the most popular candidates for the tipper treatment, with Renault and Leyland Daf fighting it out for second place in the popularity stakes.

Customers include a number of London boroughs, and local authorities as far flung as the Shetland Islands, and Devon & Cornwall. The hire companies also make use of Tipmaster bodies, and the company says it has a full order book, despite the minor slump that seems to have affected a number of other bodybuilders.

Buyers in this sort of market demand longevity and a competitive price. Product liability legislation seems to have put the frighteners on a number of customers; they are looking closely at the manufactur ers' recommendations for the size an style of a body before deciding on a par ticular product.

Booming or not, Tipmaster has had t( take notice of these demands from its cus tomers. It is a bank stockist for a numbe of manufacturers, and offers a three-yea warranty on all its bodies. "Small tipper are the most abused vehicles on the mar ket," says Tipmaster's Kevin Ibrahim who works closely with several manufac turers on their recommendations for tir per dimensions and styles.

The steel body on our test vehicle OM es with a small electro-hydraulic powere front-end rain and dropsides. There ar over-centre clips for the sides: the re2 tailgate is secured by locking pins to all°, its complete removal. We had no prot lems with body distortion when fully-lade (which has affected other tipper bodies w have tested) and found the construction I be of a high standard throughout. TI: front-end bolster is no doubt useful f( carrying ladders, but we would prefer be without the large square constructic on the top, which caught on overhangir branches. The rudimentary wheel arch( proved up to the job, although for off-rox. work we think a beefier constructi( would be preferable.

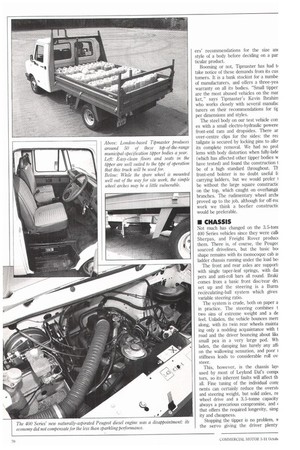

• CHASSIS

Not much has changed on the 3.5-toni 400 Series vehicles since they were cal Sherpas, and Freight Rover produc( them. There is, of course, the Peugec sourced drivelines, but the basic bo( shape remains with its monocoque cab a: ladder chassis running under the load be

The front and rear axles are support, with single taper-leaf springs, with dai pers and anti-roll bars all round. Braid: comes from a basic front disc/rear dn set up and the steering is a Bunn recirculating-ball system which gives variable steering ratio.

The system is crude, both on paper a in practice. The steering combines t two sins of extreme weight and a de feel. Unladen, the vehicle bounces men along, with its twin rear wheels mainta ing only a nodding acquaintance with t road and the driver bouncing about like small pea in a very large pod. Wh laden, the damping has barely any aff( on the wallowing sensation, and poor stiffness leads to considerable roll ov steer.

This, however, is the chassis lay( used by most of Leyland Des comp( tors, so its inherent faults will affect th all. Fine tuning of the individual comi nents can certainly reduce the overst( and steering weight, but solid axles, re wheel drive and a 3.5-tonne capacity always a precarious compromise, and that offers the required longevity, simp ity and cheapness.

Stopping the tipper is no problem, v the servo giving the driver plenty ssistance. The rear axle load limiting deice was not the most effective we have ome across, howeVer, as the rear axle snded to lock up when the vehicle was inning unladen.

1 PERFORMANCE

he naturally-aspirated Peugeot engine ives away 17.7kW (23.7hp) to the blown ersion — and it shows. Fully-laden opration is hard work, much of it in third or )urth gear on A-roads. The cab's poor srodynamics restricts motorway speeds, tile the lack of power restricts acceleraon. On the motorway, small hills will ipidly eat into the vehicle's speed, espeally if it is left to lug in fifth gear.

So the tipper is slow on the open road, at what is the vehicle going to be used tr? Most of its time will be spent on -tort journeys, and standing still while sing laboriously filled with rubble by and. Clearly, performance will not be a tajor factor.

Unfortunately the engine is noisy as ell, which is less forgiveable. Revving trough the gears to try to get a bit more )eed only produces the unedifying sound ' a hard-pressed diesel engine.

When this is combined with the test shicle's diesel-smelling cab, it did about ; much good to our tester's digestion as atching a cigarette stubbed out into the yolk of a fried egg.

Neither do the gear ratios help much when urging the little truck up the road. There is a large gap between third and fourth gears, which is too much for the engine to cope with under normal conditions. There is also the matter of the Peugeot-sourced gearbox, which replaces the 77mm Land Rover gearbox used on the old models with the Land Rover diesel engine. We liked that gearbox. It was a bit notchy, and needed rough edges knocked off, but the change quality was good.

At the Peugeot-engined 400 Series launch in March this year, Leyland Daf light-heartedly called the Peugeot gearbox installation "an interesting case of AngloFrench relations". There was clearly some breakdown in the entente cordiale, as what the 400 Series has ended up with is a rubbery horror of a gearbox. The change quality is similar to that of early Renault 5s. And once lost in the process of changing gear, finding a way out becomes a fumbling embarassment of graunches, grates and gasps.

The tipper's fuel economy of 13.81itl 100km (20.5mpg) is only slightly better than the turbo version's 14.01it/100km (20.3mpg), and significantly worse than the Land Rover-engined Sherpa van's 12.51it/100km (22.7mpg). Of course the tipper has the aerodynamics of the National Gallery extension, but one is tempted to ask, what price progress? Especially when the naturally-aspirated Peugeot unit is only marginally quieter than the raucous Land Rover engine.

• INTERIOR

As mentioned, the cab reeked of diesel. We searched for the source, but it remained a mystery, although we did notice that when the vehicle was stationary with the engine running, the cab cooling air was heated on its convoluted journey over the engine to the face-level vents.

The Manhattan skyline profile of the fascia looks just like that of the smaller 200 Series Leyland Daf vans. There is no locking glove box in the cab, although a large tray in front of the passenger seat suffices to tame the wayward impulses of the drivers' impedimenta.

Our test tipper was fitted with an extra passenger seat, which leaves little room in the cab when occupied, but the seats are comfortable and the practical trim coverings should be easy to brush clean. The floors are finished in hard rubber, which should also be simple to sweep out. The instruments and switches will be familiar to Maestro drivers. They are easy to read and use, and we particularly like the adjustable delay on the wiper switch.