• Keeping trucks for eight years and up to 650,000km

Page 42

Page 43

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

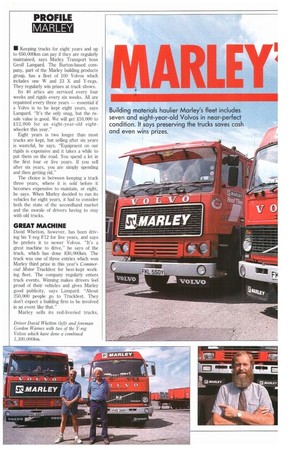

can pay if they are regularly maintained, says Marley Transport boss Geoff Lampard, The Burton-based company, part of the Marley building products group, has a fleet of 100 Volvos which includes one W and 23 X and Y-regs. They regularly win prizes at truck shows.

its 40 artics are serviced every four weeks and rigids every six weeks. All are repainted every three years — essential if a Volvo is to be kept eight years, says Lampard. "It's the only snag, but the resale value is good. We will get £10,000 to £12,000 for an eight-year-old eightwheeler this year."

Eight years is two longer than most trucks are kept, but selling after six years is wasteful, he says. "Equipment on our rigids is expensive and it takes a while to put them on the road. You spend a lot in the first four or five years. if you sell after six years, you are simply spending and then getting rid."

The choice is between keeping a truck three years, where it is sold before it becomes expensive to maintain, or eight, he says. When Marley decided to run its vehicles for eight years, it had to consider both the state of the secondhand market and the morale of drivers having to stay with old trucks.

GREAT MACHINE

David Whetton, however, has been driving his Y-reg E12 for five years, and says he prefers it to newer Volvos. It's a great machine to drive," he says of the truck, which has done 830,000km. The truck was one of three entries which won Marley third prize in this year's Commercial Motor Truckfest for best-kept working fleet. The company regularly enters truck events. Winning makes drivers feel proud of their vehicles and gives Marley good publicity, says Lampard. "About 250,000 people go to Truckfest. They don't expect a building firm to be involved in an event like that."

Marley sells its red-liveried trucks, Driver David Whetton (left) and foreman Gordon Warnes with two of the Y-reg Volvos which have done a combined 1,300,000km.

to its own subcontractors, when the truction industry is peaking. High in.t rates and the chance that Volvo will

uce a new model in 1990 also influ when it buys and sells, as does the bility that bigger trucks could be • legal before 1998.

rley Transport is an autonomous diary of Marley — a multi-national limited company making a range of g products. It has to tender for y contracts along with outside trans port companies, and has deals with three Marley companies which make roof tiles, paving and prefab garages. It has 11 depots, all based at Marley manufacturing sites, and carries products between factories and customers.

It can draw on 300 extra subcontractors during busy periods and regularly uses about 70, all of whom drive their own trucks. It also does some third-party work for non-Marley companies, but this only accounts for E1 million of its £11 million turnover. Most of it is done as backloads.

Marley Transport is highly vulnerable to the .ups and downs of the building trade,

says Lampard, who joined the company as a clerk 25 years ago. However, as a specialist, it is guaranteed most work and has fewer competitors. "We're the only ones to be making money. General hauliers are finding it hard," he says.

The company's clout is clear in its dealings with owner-operator subcontractors which depend on Marley for work. "We can change the rates we pay casuals," says Lampard. "If one rings at 4.30pm, desperate for a return load, the chances are he'll take it for a lower rate. You have to be commercially sharp."

GOOD MONEY

Marley's own drivers earn good money, he says. They are paid by the load rather than the hour, and arrange their own working week. This is an incentive to the driver to start at the time that suits each particular job. If a load has to go from Burton to Glasgow, a driver might start at 4.30am and deliver in time to complete another job before finishing, he explains.

However, Marley is strict with drivers who speed in a bid to complete a job more quickly. The knack with experienced employees is to know which roads to take and when traffic will be lightest, says Lampard. The company also prefers to use its own drivers, rather than subcontractors, on some deliveries.

The company runs its own driving competition every two years, which 48% of employees enter. They can only take part if they have had an accident-free 12 months. It follows the national Lorry Driver of the Year format. All employees enter LDoY and the best scorers qualify for Marley's own final.

"The idea is to encourage safe driving," says Lampard. "We were having a lot of petty accidents. Nobody goes out to have an accident, so we can't just eliminate them. But there is some carelessness — backing into bricks and the like. We could have tackled it by penalties, but we don't believe in doing it that way,"

Instead, Marley approached the problem in a positive way, he says. All drivers like to be appreciated and have fun, so a competition was devised to encourage them. Finalists, their wives and other drivers spend the weekend in a hotel. Two winners get a trip to Sweden, cow-tesy of Volvo, and Hiab also has a prize.

Marley Transport has been around for as long as its parent — 65 years — but has only been in its present form since the early 1980s. Most of its trucks are fitted with cranes. The rigids have either midmounted roll-loader or detachable ones. There is one ERF and an L-reg AEC Matador on its fleet, although the AEC is kept only for show purposes.

Although Lampard is proud of his veteran trucks, he does not like the image of Marley as a company running old crocks. "We have a mixed age fleet," he explains.

by Murdo Morrison