THAT NLV VEHICLE.. • 46 E VERY Commercial Motor Show must

Page 76

Page 77

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

give hauliers something to think about. Some operators have more cause for consideration than others—for example, those whose vehicles are approaching or May actually have reached the stage at which their replacement will be an economy. Many of them will find the position somewhat difficult, and whatever consideration they do give to it will be of a doleful turn, something on these line. "I wish to goodness I'd dcine as S.T.R. had so often advised and put on one side my 'depreciation money.' I should have had enough by now to purchase a new vehicle and hardly feel the outlay." Alterna-. tively, with, perhaps, a little less regret, but with some apprehension as to the future and the extra cost involved: " I can get a few pounds for my old bus and get hold of £20 or £30 to put to it, which I hope will be sufficient for the first payment on a new ' Whatsit.' That should put me on my feet again, for a little while at any rate." Now there are two problems involved in this: depreciation and hire-purchase interest. Both of these, I know, puzzle a good many hauliers; I nearly always have requests for information about them at meetings. Both

of depreciation of his vehicle. Suppose that vehicle

was a 4-5-tonner, bought about three years ago. (There are many hauliers in this position.) He must dispose of that vehicle to-day. Indeed, the wonder is that, he has not done so before. In the first place, its weight unladen is probably in the neighbourhood of 4 tons and its legal speed limit is 20 m.p.h. Until this month, he has not been unduly perturbed about the factor. of speed. Most of his work is short-distance haulage; but, in any case, whenever the opportunity has arisen, he has " chanced his arm," travelled at speeds up to and around 30 m.p.h. and, so far, has been lucky. Now he has had to put a " 20 " disc on the back of the vehicle, and this rather alarms him. He feels that the chances of his being caught when he exceeds 20 m.p.h. are now considerably increased, and he knows very well that there is not sufficient margin in his rates to allow him to spend much in fines and costs, quite apart from the fact that there is the risk of losing his licencek if it be too frequently endorsed. There is another thing, too, of which he has really been aware for some time. The_petrol-consumption rate of this vehicle is about 6-7 m.p.g.; that of the more

of them are important and especially so at the present juncture, for

the reasons given above. I will deal with depreciation in this article and hire-purchase in the next. I have another problem, also arising out of the Show and the purchase of new vehicles, and that, I hope, will be my theme for the " Problems" article in the subsequent issue.

Take first the case of the man who, at the Show, wishes that he had followed my advice and put on one side the money due on account D52

modern lightweight vehicles operated by his competitors' is 1041 m.p.g., in each Case with a payload of 5 tons. He has been contenting himself with this figure for some time, taking the view that his competitors have been putting up a bluff about the performance of their vehicles. Recently he has had incontrovertible evidence that they are right. What with that factor and 3 ao now the likelihood that he will have to keep to 20 m.p.h., he has

FIG.3 come to the conclusion that the pur chase of an up-to-date vehicle cannot much longer be delayed. He has realized that, to a large extent, his comparatively excessive petrol consumption and high Cost of operation are due in part to the fact that he is carrying so much dead weight and in part to the improved efficiency of modern vehicles. He has decided that the Show is a convenient opportunity to go into the matter thoroughly and make a change.

The question arises: suppose he had been wise and followed my advice as regards saving the amounts debited for depreciation, would he now have sufficient, in that depreciation fund, to enable him to buy a new lorry without having to find additional capital? The answer is not quite so easy to give as I should like it to be. It depends upon circumstances, and these, quite often, are of a nature to make that answer negative.

I have already suggested that his work is mainly short-distance haulage, in which ca ae it is probable that his annual mileage is moderate. Suppose that it aver

ages 14,000. The appropriate allocation of depreciation in respect of a vehicle of the size and age mentioned is a small fraction over 1d. per mile. On the basis of 14,000 miles per annum, he would have saved only £175, and that sum is obviously insufficient.

Little Sale . . .

There is still something else. There is what is often called the residual value of his vehicle, which, being translated, means the amount that he is likely to receive for it in part exchange when he buys a new vehicle. In cases of fhk kind, that amount is small. Indeed, vehicles of the type in question have little sale to-day. Even the most complacent commercial-vehicle dealer is not likely to allow more than £30 or £35. That sum, with the £175 which the operator might have saved, brings the total to only £205 or £210, as against an outlay of about MOO.

What is wrong? Why, supposing this fellow has religiously set aside his depreciation allowance, is he not in a position to purchase, with the sum so saved, plus a part-exchange allowance, a vehicle to replace his old one? Clearly, the depreciation allowance must be inadequate, but how and why? The answer is that this depreciation allowance is an average one, applying, strictly speaking, only when conditions of use are average, and 14,000 miles per annum is so far below the average that some correction must be made on that account.

What I want to do, to-day, is to put forward sorrn figures which will help hauliers whose conditions of operation are not average, so that when another show comes around two years from now, they will not find themselves in the position of having made insufficient provision for depreciation.

. Out of Date

The plain fact is that this haulier would have been comfortably placed had there been no material improvdment in the design, type and size of the vehicle used. There is plenty of life in his vehicle as yet. It is unfortunately out of date, especially in respect of unladen weight for pay-11;0, and that has proved to be his undoing.

He cannot, with his old vehicle, compete on level terms with his contemporaries operating new-type vehicles. His machine has become obsolete and his depreciation account rendered insufficient, because no provision is made for obsolescence. If his annual mileage had been double the actual figure and about average, everything would have been in order.

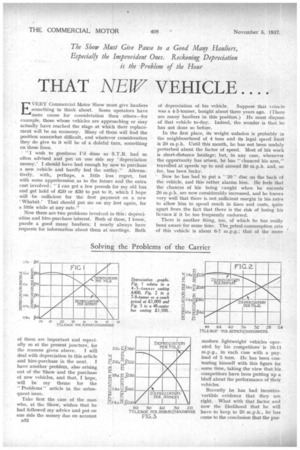

The following is a method of making provision for obsolescence . in the case of vehicles which do not cover sufficient annual mileage for the depreciation calculated on a mileage basis to equate the actual fall in market .value : The method is what mathematicians would call empirical, that is to say it is a rule bred of experience and not seeming to have any mathematical basis. I take, first of all, an average annual mileage for each type of vehicle, a figure which con forms with expectation of life according to the average

depreciation figures recommended in The Commercial Motor Tables of, Operating Cost. If the mileage

covered by the vehicle be less than that figure, a definite percentage for obsolescence must be added to that depreciation figure.

The accompanying table gives the essential information. For lightweight chassis, including the majority weighing under 21 tons unladen, the figure is 24,000 miles per annum. For more substantial vehicles, for loads of 7-8 tons and upwards, which have the advantage that they are not subject to overloading and only moderately to overspeeding, 48,000 miles per annum is the average, which figure also applies to coaches.

. . . 60,000 Miles a Year

For buses, an annual mileage of 60,000 is taken. Where the average is taken as 24,000 miles, add 5 per cent, to the normal figure for depreciation for every 1,000 miles less than that average. Where it is 48,000, add 5 per cent, for evoy 2,000 miles below the average. Where it is 60,000 add 5 per cent, for every 3,000 miles below the average.

What all this really means is that there is a certain minimum figure for depreciation plus obsolescence, that is to say, there is a minimum amount which must be set aside on that account and that figure can be arrived at by the method outlined in this article.