Lt.-Corn._ J. W. Thornycroft

Page 24

Page 25

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

afety Demands Taxation by Gross U7eght

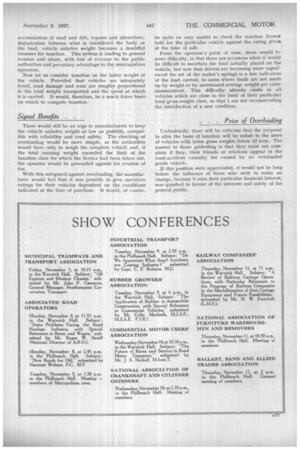

SH01.51,D taxation be levied on the basis of vehicle Unladen weight, or on gross laden weight? This question is becoming an increasingly nreportant matter, and must, in the near future, be dealt with by the Chancellor of the Exchequer.

The basis of taxation on unladen weight was decided on as being the simplest to operate, and was not objected to at the tithe by users or manufacturers because the amount of taxation was relatively small and did not differ greatly between the various classifications. For example, for a vehicle exceeding 5 tons unladen weight, a tax of a million vehicles and some 200,000 operators, especially when it costs less, owing to the regulations and scheme of taxation, to operate overloaded and relatively unsafe machines? The accompanying table explains why this is the case. It will be seen that Vehicle B can carry legally only ton more useful load than Vehicle A, and then only at 10 m.p.h. lower speed, at an additional annual tax of £20 and at a higher interest on capital charge. Vehicle B is safe; A is a menace to the public unless maintained in first-class condition, which is rarely the case, owing to the only £48 was paid in 1929, against the present figure of £110 for a vehicle with a gross weight laden of 22 tons. In the early stages, the greater taxation on the heavier vehicles increased the incentive to manufacturers to reduce tare weight and was beneficial to the user and the road authorities. Now, however, the evasion-of-tax urge, plus the restriction of speed to 20 m.p.h. in the case of vehicles over 2-i tons, has had the effect of encouraging users to disregard manufacturers' ratings. and creating unwise competition between makers in rating the capacities of their chassis for a greater load than those of their rivals, particularly within the 2i-ton taxation class.

Small Safety Margin .

Neither of these tendencies can be in the public interest, as vehicles are now being operated with little, if any, margin of safety. Agreed that there is now a large number of examiners to check these unsatisfactory tendencies, but how can 150 officials compete with half growing policy of running a vehicle to death in three years or less.

Another aspect of this problem is the suitability of domestic types for the export market. The urge to reduce weight necessitates lightweight, high-revolution, " racehorse " design in power units. These are not suitable for export markets, where efficient maintenance equipment and personnel are not available.

In Wartime

A reserve of vehicles of suitable type in commercial use, which can be impressed for war service, is another important matter. Here, again, the small high-speed lightweight power unit and chassis with minimum-size tyre equipment would not be the most suitable. Difficulty in deciding what should be included in the chassis unladen weight is a further problem. There is a definition in the Finance Act, but how it is interpreted by the operator is another matter. As a result of the accumulation of mud and dirt, repairs and alterations, demarcation between what is considered the body or the load, vehicle unladen weight becomes a doubtful measure for taxation. This system is leading to general evasion and abuse, with loss of revenue to the public authorities and pecuniary advantage to the unscrupulous operators, Now let us consider taxation on the laden weight of the vehicle. Provided that vehicles are adequately tyred, road damage and wear are roughly proportional to the total weight transported and the speed at which it is carried. It would, therefore, be a much fairer basis on which to compute taxation.

Signal Benefits .

There would still be an urge to manufacturers to keep the vehicle unladen weight as low as possible, compatible with reliability and road safety. The checking of overloading would be more simple, as the authorities would have only to weigh the complete vehicle and, if the total running weight exceeded the limit of the taxation class for which the licence had been taken out, the operator would be proceeded against for evasion of tax..

With this safeguard against overloading, the manufacturer would feel that it was possible to give operators ratings for their vehicles dependent on the conditions. indicated at the time of purchase. It would, of course. be quite an easy matter to check the taxation licence held for the particular vehicle against the rating given at the time of sale.

From the operator's point of view, there would bc some difficulty, in that there are occasions when if be difficult to ascertain the load actually placed on the vehicle, but now that drivers are becoming more experienced the set of the maker's springs is a fair indication of the load carried, in cases where loads are not made up by weight or by ascertained average weight per cubic measurement. This difficulty already exists in all vehicles which are close to the limit of their particular total gross-weight class, so that I am not recommending the introduction of a new condition.

. Price of Overloading

Undoubtedly there will be criticism that the proposal to alter the basis of taxation will be unfair to the users of vehicles with laden gross weights below 12 tons. The answer to those protesting is that they must not complain if they, their friends or relations appear in the road-accident casualty list caused by an overloaded goods vehicle.

If this position were appreciated, it would not be long before the influence of those who wish to make no change, because it suits their particular financial interest, was quashed in favour of the interests and safety of the general public.