The FUTURE of the

Page 126

Page 127

Page 128

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

TRANSMISSION

Are We at the Threshhold of a Period of Rapid Development ? Promising Types of Mechanism which are Undergoing Experiment at the Present Time.

• ONSISTENT readers of The Commercial Motor

will scarcely need to be reminded that we have always kept closely in touch with transmission developments, and have advocated any change likely to increase the efficiency, safety or convenience of commercial vehicles. There are, of course, many sides to this problem; for the driver it is the difficulty of changing gear with rapidity and silence that constitutes the chief fault of the orthodox sliding-type gearbox; to the maintenance engineer the damage done by careless gear changing is most prominent. Then there is the chassis designer, who is hampered in many ways by being limited to the use of three or four forward speeds ; for example, he has to submit to using a relatively low topgear ratio, which means that on a level main road the engine of, say,

a long-distance coach or express van is turning at a much higher speed than is really necessary from the point of view of power output.

On passenger vehicles the noise so often produced by indirect gears is a strong argument in favour Of a better system, particularly for the much-used third speed, which is brought into action on many long hills for minutes at a time. In any case, the emission of noise by a mechanism indicates the presence of power losses and the occurrence of wear.

Against these disadvantages it is only fair to remark upon the fact that the orthodox gearbox, owing to the way it has been improved year by year for nearly three decades, has become an extraordinarily reliable piece of mechanism, and one which withstands harsh treatment surprisingly well. Consequently, inventors who set out to produce anything so revolutionary as an infinitely variable and automatic system for conveying power, are up against very strong competition and what may be termed " vested interests." As a natnral result the tendency during the past year or so has been to concentrate upon modifications or additions to the orthodox 'gearbox such as are calculated to rectify its faults without necessarily involving sweeping changes of design.

Using Gears with Helical Teeth.

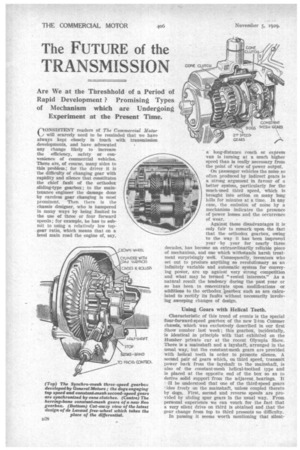

Characteristic of this trend of events is the special four-forward-speed gearbox of the new 2-ton Commer chassis, which was exclusively described in our first Show number last week.; this gearbox, incidentally, is identical in principle with that exhibited on the Humber private car at the recent Olympia Show. There is a mainshaft and a layshaft, arranged in the usual way, but the constant-mesh gears are provided with helical teeth in order to promote silence. A second pair of gears which, on third speed, transmit power back from the •layshaft to the mainshaft, is also of the constant-mesh helical-toothed type and is placed at the opposite end of the box so as to derive solid support from the adjacent bearings. It

ill be understood that one of the third-speed gears *rides freely on the mainshaft, unless coupled thereto by dogs. First, second and reverse speeds are provided by sliding spur gears in the usual way. From personal experience we can vouch for the fact that a very silent drive on third is obtained and that the -gear change from top to third presents no difficulty.

In passing it seems worth mentioning that silent third gearboxes of a similar • type are also used on private cars by the Riley concern, the M.G. Car Co., and PanhardLevassor. Similar in conception is the new Reo gearbox, affording three forward speeds with top direct and second speed through constant-mesh gears which have herring-bone teeth specially designed to give silent running. Here, again, sliding dogs are used to select the ratio required.

Quite different in conception are the American " twin-top " gearboxes used on a number of 1930-type private cars, but not, so far, developed for commercial work. The Graham-Paige is a typical example, and we reproduce a drawing showing the gears and shafts. It will be noticed that top gear is direct and that the third speed is obtained through a special system of internal gears (A and B) which provide a reduction of about 11 to I. These gears run extremely silently, and a study, of the illustration will show that the selection by clogs (C and D) is so arranged as to give a very easy gear change, owing to the fact that there is only a small difference in the rotational speeds of the parts to be coupled together.

" Overdrive " to reduce Engine Speed.

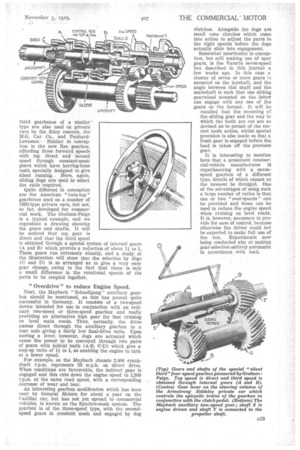

Next, the Maybach " Schnellgang " auxiliary gearbox should be mentioned, as. this has proved quite successful in Germany. It consists of a two-speed device intended for use in conjunction with an ordinary two-speed or three-speed gearbox and really providing an alternative high gear for fast cruising on level main roads. Thus, normally, the drive passes direct through the auxiliary gearbox to a rear axle giving a fairly low final-drive ratio. Upon moving a lever, however, dogs are actuated which cause the power to be conveyed through two pairs of gears with helical teeth (A-B, C-D) which give a step-up ratio of 11 to 1, so enabling the engine to turn at a lower speed.

For example, on the Maybach chassis 2,400 crankshaft r.p.ra. represents 53 m.p.h. on direct drive. When conditions are favourable, the indirect gear is engaged and this cuts down the engine speed to 1,500 r.p.m. at the same road speed, with a corresponding decrease of wear and tear.

An interesting gearbox modification which has been used by General Motors for about a year on the Cadillac car, but has not yet spread to commercial vehicles, is known as the Synchro-mesh system. The gearbox is of the three-speed type, with the secondspeed gears in constant mesh and engaged by dog clutches. Alongside the dogs are small cone clutches which come into action to adjust the parts to the right speeds before the dogs actually slide into engagement.

Somewhat unorthodox in conception, but still making use of spur gears, is the Varatio seven-speed box described in this journal a few weeks ago. In this case a cluster of seven or more gears LI mounted on the layshaft, and the angle between this shaft and the mainshaft is such that one sliding gearwheel mounted on the latter can engage with any one of the gears on the former. It will be recalled that the mounting ol!

the sliding gear and the way in which the teeth are cut are so devised as to permit of the cor rect tooth action, whilst special provision is also made so that a fresh gear is engaged before the load is taken off the previous gear.

It is interesting to mention here that a prominent commercial-vehicle manufacturer 0 experimenting with a sevenspeed gearbox of a different type, details of which cannot at the moment be divulged. One of the advantages of using such a large number of ratios is that one or two "over-speeds" can be provided and these can be used to reduce the engine speed when cruising on level road, It is, however, necessary to provide for ease of control, because otherwise the driver could not be expected to make full use of the box. Experiments now being conducted aim at making gear selection entirely automatic in accordance with load,

Next in logical sequence come devices auxiliary to the ordinary gearbox, for the purpose of simplifying gear changing and presenting certain special advantages. The most important of these is undoubtedly the free wheel, which, despite its relatively slow progress, has gained many strong adherents. A point which appeals particularly to engineers operating fleets of vehicles mainly used in heavy traffic, is that as the free wheel cuts out reversals of stress on the over-run and shocks due to bad gear-changing, the cost of maintenance work on the transmission is very greatly reduced. The amount a coasting which the free wheel permits varies in accordance with conditions, but can at any rate be expected to produce a reduction in petrol consumption of the order of 15 per cent.

Examples of the Free-wheel Device.

A number of free wheels is available, of which three well-known examples are the Iiumfrey-Sandberg, the de. Lavaud and the Millam. The first-named and last-named fit between the gearbox and the propeller shaft, whereas the de Lavaud takes the place of the ordinary differential and presents the additional advantage that it will not allow one wheel to spin ineffectively. The Millam device, incidentally, embodies a sprag which effectively prevents the vehicle from running backwards downhill and which, therefore, facilitates restarting on a gradient.

The free wheel, by permitting coasting to occur, naturally throws somewhat more work and responsibility upon the braking system than is usual. Furthermore, unless the idling jet be carefully set the engine may stop during a coasting period. Consequently, a free wheel and a vacuum servo motor for brake application do not make a happy combination.

In addition to these mechanical devices, all of which employ rollers gripped between metal surfaces, there is the Clayton-Currin coaster clutch, which will be shown at Olympia in a re-designed form. This consists of a friction clutch, auxiliary to the main clutch, the parts of which are normally held in an operative position by a spring. Acting against the spring is a diaphragm operated by engine suction, so that when the throttle is closed the depression in the inlet pipe disengages the clutch. Should the engine stop during coasting it is automatically re-started. This clutch is now incorporated in the gearbox in such a way as to be operative for coasting purposes only when top gear is engaged, but its action in permitting ease of changing is retained for the other gears.

Dog Clutches in the Transmission Line.

Yet another scheme for easy gear-changing consists of using a species of dog clutch in the transmission line behind the gearbox, interconnecting this mechanism with the main clutch so that both are thrown out simultaneously when the pedal is depressed. Provision must be made to synchronize the speeds of the dogs for quiet re-engagement; in the Salerni coupling, for example, a floating ring is utilized for this purpose.

This review of the subject would be incomplete without reference to epicyclic and electrical systems, which, incidentally, are combined in an entirely new device which we shall shortly be able to describe. In epicyclic gearing, as is well known, changes of ratio can be effected simply by alternatively braking and freeing various trains of gears, and, furthermore, the parts can be arranged to run with a high degree of silence.

The Wilson gearbox, which has been used on certain Armstrong Siddeley private cars with such success for over a year, is an excellent example of a clever use of the epicyclic principle. Then there is the Trojan system which has proved very successful for light vans. Another epicyclic gear is the Cotal, in which, instead of employing friction brakes, the gears are controlled by electro magnets. The gear lever, therefore, simply constitutes an electrical switch.

The Tilling-Stevens petrol-electric system is, of course, well known, and has for long given excellent results in practice, but it has the disadvantages weight and bulk which limit its application to the large and powerful class of chassis.

Finally, there are the infinitely variable gears such as the de Lavaud, in which a smash plate of variable angle is employed, the R.A..V.S., utilizing friction discs in a new manner, the Constantinesco inertia gear, the Thomas power unit combined with a system of variable cranks and so forth. So far these have not progressed very far beyond the experimental stage, although certain of them have shown what an excellent performance can be attained by applying devices of this character to the petrol engine.

Summing up, the tendency at the moment would appear to be towards a more extended use of devices and modifications which tend to remove the worst faults of the orthodox gearbox without any vital changes in principle. At the same time more revolutionary ideas are still being worked upon and it may well be that in due course some of them will come to fruition. Developments may be hastened by the more extensive use of engines of the Diesel type, for which a fairly constant speed is desirable.