Dennis Maxim/Pitt

Page 52

Page 53

Page 54

Page 57

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

30-ton-gross ark

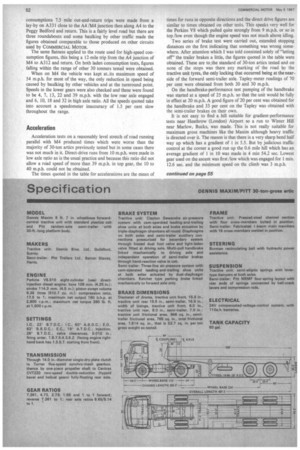

By A J. P. Wilding, AMIMechE, MIRTE WHEN the Dennis Maxim was introduced at the 1964 Commercial Motor Show the tractive unit model was designed for operation at 32 tons gross train weight. But because Dennis considered that the Cummins V8 power unit fitted at that time did not give enough power to match this figure, the chassis was derated to 26 tons. Now a Perkins V8.510 is used in the model and following a programme of proving tests which are said to have shown that a higher gross weight is practical, Dennis uprated the chassis to 30 tons g.t.w. only two weeks ago.

Following a full road test of the latest version of the Maxim coupled to a Pitt semi-trailer and running at just over the 30 tons g.t.w. limit, 1 have some reservations on whether there is enough power available. The Maxim performed at an acceptable level on the test but this was mainly over relatively flat roads and it was noticeable that the slightest adverse gradient pulled the speed down. And even where the road was virtually flat it required a long distance to get up to 40 m.p.h. from a standstill.

Even so the acceleration times recorded were reasonable, a great help here being well-spaced gear ratios which in conjunction with a two-speed axle gave 10 distinct forward gears. Much of the credit for the acceptable performance must go to the transmission set-up for at 30 tons gross the power-to-weight ratio of the Maxim is only 5.31 b.h.p. per ton when basing this on the 160 b.h.p. maximum net output of the Perkins V8.

The Maxim is the first vehicle that has been tested with the Perkins V8 and this unit was found to have a number of good characteristics. One of the most important was an excellent torque "back-up". Maximum net torque of 380 lb. ft. is produced at 1,500 r.p.m. but even at speeds as low as 1,000 r.p.m. there was a good pull-away despite the 30 tons weight. Fuel consumption at 7.5 m.p.g. for trunk-road running and 6.8 m.p.g. for a high-speed motorway journey was comparable to that obtained on a number of 30-ton-artic tests; lower than some of the better figures obtained but it is usual to find much worse economy when the power-toweight ratio is down.

The Maxim design is very good on paper—generally confirmed on the test—and this is particularly true of the brakes. One feature I like is that the secondary system is a complete duplication of the service brakes. Good figures for brake tests were obtained and there was a good "feel" on normal driving. Power steering made light work of driving the artic and the overall impression was of a much lighter outfit.

The standard transmission used by Dennis in the Maxim is now the Turner T5 C 4001 five-speed synchromesh gearbox which is based on American Clark design. It is mounted as a unit with the Perkins engine, the drive to the box being through a 14 in. singleplate clutch which is operated by a direct mechanical linkage. The rear axle in the test vehicle was from the range of American Rockwell-Standard designs now manufactured under licence by Centrax Ltd., of Newton Abbot.

The two-speed driving head has hypoid-bevel primary reduction and from the bevel-wheel shaft the drive is taken to the differential carrier by single-helical gearing. There are two pairs of helical gears, one for each of the axle ratios and the particular ratio is selected by a dog clutch on the bevel-wheel shaft. Dennis use an air-operated engagement system which was found to be foolproof on the test.

On the test vehicle Clayton Dewandre light-laden valve equipment was fitted to reduce the effort at the driving axle brakes under empty or part load conditions. The equipment on the Dennis was of an experimental nature, the sensing unit being connected to dual regulating valves, one for the main and one for the secondary system.

To my mind the layout used by Dennis should be copied by all manufacturers. The usual practice is to have outer axle braking for the secondary system and while it is preferable to omit the driving axle brakes rather than those on the other axle on the grounds of stability, improved stability is not the real reason: it is usually cheapness.

For if it is dangerous to lock the driving wheels, then why are these included in the service brake system? It must be better to have brakes on all the wheels for the secondary system—less effort need be applied if felt desirable because a lower efficiency is required. And to answer those who say that a duplicate layout would need two light-laden valves at the driving axle there is the example of the equipment fitted on the Maxim.

With the advent of secondary systems, current maximum gross tractive units rarely have a hand valve in the cab for independent operation of the semi-trailer brakes. The Dennis has one of these which I would say is rather superfluous and I would suggest that this equipment be dispensed with and the money spent on changing from a purely mechanical multi-pull handbrake to an air-assisted single-pull type; the handbrake was the only thing about the Maxim that made one think of the "good old days".

The semi-trailer supplied for the test was from the latest Pitt range, being fitted with that company's NRMF four-spring suspension system. This has the rear ends of the springs on each side connected through bell-crank levers and rods in compression to provide no-hop characteristics. The suspension performed %cry well and the semi-trailer which has fabricated I-beam main members appeared to be robustly constructed.

One very good point about the design is that by having the platform deck flush with the tops of the main members loading height is at a minimum. And another good feature is that the unit is fairly light, having a kerb weight of only 3 tons 16.75 cwt.

Lightness was, in fact, an interesting feature of the whole outfit for with the Maxim weighing only 4 tons 14.25 cwt. a payload of almost 21.5 tons was possible. Even with a longer semi-trailer33 ft. would have been possible—a payload of over 21 tons could have been carried which is about the maximum figure paacticable with most 32 tons gross five-axle artics employing one of the lightest three-axle tractive units available.

All laden tests were carried out at the weight of 30 tons 3.5 cwt. and most of the running was in the area around M4 between Heathrow (London) Airport and Slough. For normal-road fuel

consumptions 7.5 mile out-and-return trips were made from a lay-by on A331 close to the A4 /M4 junction then along A4 to the Peggy Bedford and return. This is a fairly level road but there are three roundabouts and some baulking by other traffic made the figures obtained comparable to those produced on other circuits used by COMMERCIAL MOTOR.

The same flatness applied to the route used for high-speed consumption figures, this being a 12-mile trip from the A4 junction of M4 to A312 and return. On both laden consumption tests, figures falling within the range of other 30 tonners tested were obtained.

When on M4 the vehicle was kept at. its maximum speed of 54 m.p.h. for most of the way, the only reduction in speed being caused by baulking by other vehicles and at the turnround point. Speeds in the lower gears were also checked and these were found to be 4, 7, 13, 22 and 39 m.p.h. with the low rear axle engaged and 6, 10, 18 and 32 in high axle ratio. All the speeds quoted take into account a speedometer inaccuracy of 1.5 per cent slow throughout the range.

Acceleration Acceleration tests on a reasonably level stretch of road running parallel with M4 produced times which were worse than the majority of 30-ton artics previously tested but in some cases there was not much in it. Direct-drive runs from 10 m.p.h. were made in low axle ratio as is the usual practice and because this ratio did not allow a road speed of more than 39 m.p.h. in top gear, the 10 to 40 m.p.h. could not be obtained.

The times quoted in the table for accelerations are the mean of times for runs in opposite directions and the direct drive figures are similar to times obtained on other tests. This speaks very well for the Perkins V8 which pulled quite strongly from 9 m.p.h. or so in top /low even though the engine speed was not much above idling.

Two series of brake test were carried out, extended stopping distances on the first indicating that something was wrong somewhere. After attention which I was told consisted solely of "letting off" the trailer brakes a little, the figures quoted in the table were obtained. These are to,the standard of 30-ton artics tested and on none of the stops was there any marking of the road by the tractive unit tyres, the only locking that occurred being at the nearside of the forward semi-trailer axle. Tapley-meter readings of 70 per cent were obtained from both 20 and 30 m.p.h.

On the handbrake-performance test pumping of the handbrake was started at a speed of 25 m.p.h. so that the unit would be fully in effect at 20 m.p.h. A good figure of 20 per cent was obtained for the handbrake and 33 per cent on the Tapley was obtained with the semi-trailer brakes on their own.

It is not easy to find a hill suitable for gradient-performance tests near Heathrow (London) Airport so a run to Winter Hill near Marlow, Bucks, was made. This is not really suitable for maximum gross machines like the Maxim although heavy traffic is directed over it. The reason is that there is a very sharp bend half way up which has a gradient of 1 in 5.5. But by judicious traffic control at the corner a good run up the 0.6 mile hill which has an average gradient of 1 in 10 was made in 4 min 54.2 sec. Lowest gear used on the ascent was first /low which was engaged for 1 min. 12.6 sec. and the minimum speed on the climb was 3 m.p.h.

The rise in engine coolant temperature could not be checked directly as the Maxim has an expansion tank in its system but in an ambient temperature of 13°C (55°F) the dash-mounted gauge showed a temperature rise froM 78°C (172°F) to 88°C (190°F).

To assess brake fade a run down the hill was made with top / high engaged and the service brake applied to restrict speed to 20 m.p.h. After a run lasting 1 min. 44.3 sec. a maximum pressure stop from 20 m.p.h. produced a Tapley meter reading of 72 per cent—more than the cold-drum figure!

Just past the steepest section—the sharp bend—Winter Hill has a gradient of 1 in 7. Here stop-and-restart tests were made. The handbrake held the outfit easily on the slope both facing up and facing down and when facing up a restart in first /high was possible. When facing down the hill however, a reverse thigh restart up the 1 in 7 gradient was not possible even though the main-box ratio is the same as first but a reverse /low was accomplished easily.

Factors that helped in making a smoother ascent of the hill were easy and straightforward ratio-change layouts in the Turner gear box and the Centrax axle. Selection of the forward ratios was positive although the synchromesh was a little heavy when engaging second and fourth.

From a handling point of view the Maxim was excellent. The steering was light yet had enough "feel" to allow an initial tendency to over-correct to be quickly overcome. As I have already said the brakes also had a good "feel" on normal driving with a light pedal and minimum delay in application and the accelerator was found to be well placed and the clutch not unduly heavy.

These factors add to the high standard of comfort and trim of the Maxim cab in making driving the vehicle a pleasant experience. The design is actually surprising in the number of fittings that are standard which would normally be options. These include an electric clock, cigarette lighter and ashtrays. A console in front of the steering column contains a good selection of instruments and warning lights. There is an ammeter, oil pressure gauge and air pressure gauges for the main and secondary brake systems and all four are complemented by warning lights and the last two by buzzers as well. There is also a fuel gauge, water temperature gauge and a rev, counter in addition to the speedometer, and the console also includes a button for the standard electrically operated windscreen washers.

The cab itself is double skinned in reinforced plastics with the interior roof and rear panel colour-impregnated. The insides of the doors are covered in the same material as the seats and the dash is plastic-covered and well padded. Two interior lights and two sun visors are standard and the floor and engine cowl are rubber-covered. A panel above the windscreen contains four switches and a socket for an extension lead from the vehicle electrics and one of the switches is for a "hitch" light behind the cab.

Self-cancelling flashers are standard and the warning light for these is also above the windscreen which is not the best place for it. The self-cancelling switch was not always working correctly during the test and it was not difficult to overlook the flashing light which is placed out of the normal line of vision. With so much to appreciate in a commercial vehicle cab it is somewhat churlish to find fault but I did not like the drop-type windows nor the rather primitive-looking heater controls mounted on the dash. I felt both were out of character with the design.

Visibility from the driving seat is very good and so is the heating equipment; ventilation is helped by hinged quarter lights. Access to the cab is easy and there has been a recent improvement in this respect and now the doors open through a 15° greater arc than originally.

List price of the Dennis Maxim tractive unit as tested, including all the fittings and spare wheel and carrier but excluding the loadsensing equipment in the brake system, is £3,898. The Pitt semitrailer is listed at £1,630.