IN1 MIX There are good arguments for building a complete

Page 45

Page 44

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

truck in-house — and for buying in proprietary components. CM has been talking to both camps.

Thirty years ago buying a British truck was a bit like paying a visit to the Pick'n'Mix counter at Woolworths: hauliers were able to select "component trucks" from a wide range of proprietary engines, gearboxes, axles and cabs.

There were exceptions of course — Leyland, AEC and Bedford all built their own engines — but most British heavy truck makers relied on bespoke drivelines, often based on the legendary Gardner diesel.

But in the late sixties and early seventies a new breed of imports started coming on to the market from the likes of Volvo and Scania.

Their cabs and drivelines were all built in-house. Before long the term "integrated driveline" was firmly entrenched in the language of British operators, and nowadays over 70% of all new sales go to manufacturers who build their own major driveline components.

So is the traditional UK component truck a dying breed? Bob Sculfor certainly doesn't think so. As managing director of Seddon Atkinson he sees the market for bespoke trucks as customerled: not a niche market developed by manufacturers anxious to hawk their wares.

"Last year," says Sculfor, over 17% of all heavy trucks sold in the UK were component trucks using drivelines from specialist suppliers like Cummins, Perkins, Eaton and ZE. In the sector for articulated tractors it was over 19%."

The argument for bespoke drivelines is the same now as it was in the sixties: selecting from a range of proprietary engines allows the truck maker to meet a wide variety of operator requirements.

"If there is a rapid move away from a power norm in any sector then the bespoke builder can react quicker than an in-house manufacturer by changing supplier," says Sculfor. Last year Seddon Atkinson spent 2.3.6m on engines from Cummins and Perkins with 80% of the budget going to Cummins; in 1992 it expects to double that figure.

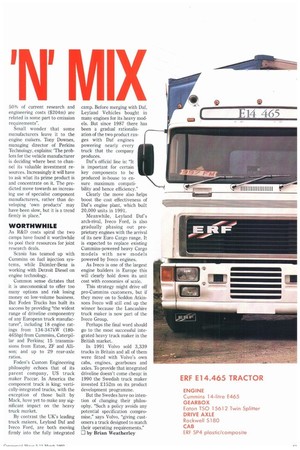

ERF is the biggest component truck maker in the UK. Its philosophy is straightforward: "We concentrate all our resources on the things that differentiate ERF, which is fundamentally the cab and vehicle engineering — putting the best components together to get the best productive vehicle," says marketing director Rod England. "The big advantage to ERF is that we don't have massive capital or resources tied-up in manufacturing plants and components. It also allows us the flexibility to choose, so if something goes out of fashion, or becomes unreliable, we don't have a vested interest in a massive amount of capacity that says you've got to keep using that."

WINNING

Last year ERF took over 13% of the artic market selling 1,039 vehicles. In a good year it takes up to 5,000 engines from Cummins and Perkins, with Cummins winning 80% of the business.

While buying-in has obvious financial advantages, the company acknowledges: "The downside is you pay a little bit more for the components, but that gets offset by the lack of R&D on components and you spend your R&D where it counts — on putting the bits together wisely," says England.

Cummins is the world's largest manufacturer of diesel engines over 150kW (200hp). It estimates that "in the region of 50% of current research and engineering costs ($204m) are related in some part to emission requirements".

Small wonder that some manufacturers leave it to the engine makers. Tony Downes, managing director of Perkins Technology, explains: The problem for the vehicle manufacturer is deciding where best to channel its valuable investment resources. Increasingly it will have to ask what its prime product is and concentrate on it. The predicted move towards an increasing use of specialist component manufacturers, rather than developing 'own products' may have been slow, but it is a trend firmly in place."

WORTHWHILE

As R&D costs spiral the two camps have found it worthwhile to pool their resources for joint research deals, Scania has teamed up with Cummins on fuel injection systems, while Daimler-Benz is working with Detroit Diesel on engine technology.

Common sense dictates that it is uneconomical to offer too many options and risk losing money on low-volume business. But Foden Trucks has built its success by providing the widest range of driveline componentry of any European truck manufacturer", including 18 engine ratings from 134-347kW (180465hp) from Cummins, Caterpillar and Perkins; 15 transmissions from Eaton, ZF and Allison; and up to 29 rear-axle ratios.

Foden's Custom Engineering philosophy echoes that of its parent company, US truck maker Paccar. In America the component truck is king; vertically-integrated trucks, with the exception of those built by Mack, have yet to make any significant impact on the heavy truck market.

By contrast the UK's leading truck makers, Leyland Daf and Iveco Ford, are both moving firmly into the fully integrated camp. Before merging with Daf, Leyland Vehicles bought in many engines for its heavy models. But since 1987 there has been a gradual rationalisation of the two product ran ges with Daf engines powering nearly every truck that the company produces.

Daf's official line is: "It is important for certain key components to be produced in-house to en sure maximum compatibility and hence efficiency."

Clearly the move also helps boost the cost effectiveness of Daf's engine plant, which built 20,000 units in 1991.

Meanwhile, Leyland Daf's arch-rival, Iveco Ford, is also gradually phasing out proprietary engines with the arrival of its new Euro Cargo range. It is expected to replace existing Cummins-powered heavy Cargo models with new models powered by Iveco engines.

As Iveco is one of the largest engine builders in Europe this will clearly hold down its unit cost with economies of scale.

This strategy might drive off pro-Cummins customers, but if they move on to Seddon Atkinsons Iveco will still end up the winner because the Lancashire truck maker is now part of the Iveco Group.

Perhaps the final word should go to the most successful integrated heavy truck maker in the British market, In 1991 Volvo sold 3,339 trucks in Britain and all of them were fitted with Volvo's own cabs, engines, gearboxes and axles. To provide that integrated driveline doesn't come cheap: in 1990 the Swedish truck maker invested E152m on its product development programme.

But the Swedes have no intention of changing their philosophy. "Such a policy avoids any potential specification compromise," says Volvo, "giving customers a truck designed to match their operating requirements." 0 by Brian Weatherley