Japan Missed Export Target

Page 45

Page 46

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

by Yoshio Ono and Hikari Endo

JAPAN'S motor industry had a 1953 export target of 10 per cent. of total output. Although some headway was made, this figure was not reached. The reason was that exported vehicles could not compete on price. Steel is expensive in Japan because it has to be imported. Japanese vehicles even failed to sell substantially in Formosa, one of the steadiest markets for the country's products,

Last year, some of the principal manufacturers concluded agreements with overseas concerns to assemble vehicles in Japan. Shin-Mitsubishi began to build Willys-Overland Jeeps. The amount of assembly work done, however, fell far short of expectations, because of strikes and factory reorganizations.

Production of Japanese-designed models rose steadily throughout the year and a monthly record was estab , lished in December, when 61 per cent. more vehicles were made than in the corresponding month of 1952. Because of lack of money, the Japanese Forces have not yet placed big orders for special-type vehicles.

A tendency to install engines of higher power developed. Units of 95 b.h,p., instead of 85 bp, were designed for Nissan models. Datsu replaced 20 b.h.p. engines in their small goods vehicles with 25 b.h.p. units, whilst Toyopet substituted 45 b.h.p_ engines for 27 b.h.p. units in their light lorries.

The Fuso 110 b.h.p, engine was outmoded by a 130 b.h.p. product, At the same time as these larger engines were introduced into various vehicles, the carrying capacity was correspondingly up-rated.

Competition in pr ice between Japanese manufacturers became keener, beginning when the cost of Toyopet lorries was cut from 950,000 yen (about £942) by 150,000 yen (approximately £149). Soon afterwards, Nissan, Ohta and other companies reduced their prices, stating that it was made possible by internal economies.

However, it was observed that the reductions were really the disgorging of some part of the undertakings' excess profits. Imported vehicles offered greater competition last year because they could be brought into the country without licences.

From January-October, 1953, 17,789 lorries were made. Petrol-vehicle production by respective manufacturers was as follows: Toyota 5,638; Nissan 5,452; Isuzu 1,805; Hino 36; and Fuso 15. Isuzu made 3,081 oilers, Mina 632, Minsei 611, Fuso 344 and Nissan 175.

Bus production totalled 3,611. Oilengined models predominated, of which Isuzu made 1,482, Hino 748, Fuso 406, Nissan 214 and Minsei 140. Toyota made 402 petrol buses, Nissan 183, Isuzu 35 and Fuso one.

In the light-delivery class. Toyota produced 3,709 vehicles, Nissan 2,949, Ohta 1,465 and Prince 1,197.

On August 31, 1953, 492,281 commercial vehicles were registered in Japan, broken down as follows:— Heavy and medium lorries, 148,418; light goods vehicles, 54,708; threewheelers, 258,909: haulage tractors, 531; haulage trailers, 2,455; buses, 26,632; passenger transport tractors, 327; and passenger transport trailers, 301.

The Japanese road passenger transport industry celebrated its 50th anniversary last year.

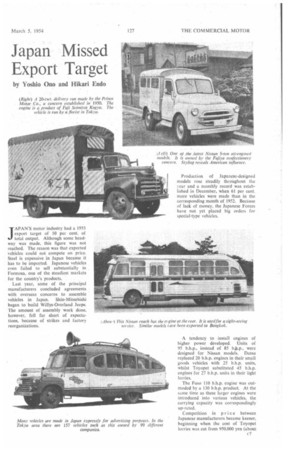

The bodybuilding industry flourished and many vehicles for advertising were built to special designs. There are 157 such vehicles in the Tokyo area.

A double-deck bus based on an Isuzu oil-engined chassis was built for advertising purposes by the Kongo Seisakusho concern of Tokyo. It was possibly the first double-decker to be made in the country. With the exception of those used by British Overseas Airways Corporation, such vehicles are rare in Japan.