Why Not

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

ROADS ABOVE IE RAILWAYS?

NTO one who has even a superticial knowledge of the road transport of goods and passengers can but believe that the future holds vast possibilities of traffic increase. Every day more and more vehicles —private and commercial—are being brought into service, and the rate of increase is far more likely to rise than to fall. Upon its development depends, to a great ex tent, the national welfare, and we have still a very long way to go before we reach the proportion of vehicles to population which exists in the United States.

The main problem is, however, how our roads can be made ade quately to cope with the traffic likely to exist in the near future. Already there is distressing con gestion in many busy centres of population, and the authorities are finding the work of superintending this traffic increasingly difficult. In the smaller towns and rural areas there is hardly likely to be con siderable congestion for some years to come, and the trunk roads which have already been built, and are likely to be constructed, in the future, will probably be able to meet our early needs in this direction.

The great diffieulty is to obtain access to these main arteries of . traffic, and this is where a vehicle, whether it be private or commercial, has often to waste so much time.

For instance, once a vehicle is on the Great West Road it can keep up a very fair average speed, but to reach this road from, say, the offices of this journal it has to tra verse many busy, and often congested, thoroughfares. This, during certain times of the day, may occupy possibly an hour, although the distance is only nine miles.

To extend such a road much farther into the centre would in volve an enormous expenditure, the destruction of a huge amount of valuable property and the rebuild ing of a number of bridges. The

same remarks apply to practically any other trunk road, and the prob lem is how such a drastic procedure can be avoided. It is certain that something must be done—and that quite soon.

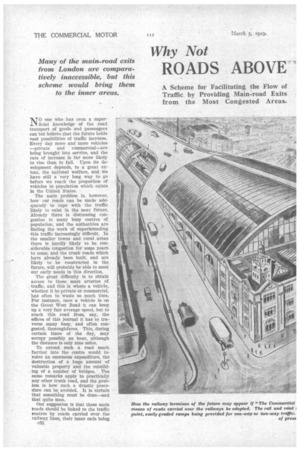

Our suggestion is that these main roads should be linked to the traffic centres by roads carried over the railway lines, their inner ends being c32 at the railway termini. The idea may seem somewhat revolutionary, and we are quite prepared to admit that there aremany difficulties in the way of its execution, but difficulties exist to be surmounted. The railway companies would, no doubt, object violently. Some critics also may suggest that the cost would be so enormous as to rule out the possibility of such roads, but after a close study of the question we do not believe that the expenditure would need to be nearly so great as might at first be thought. Other cities have elevated railways, so why should we not have elevated roads? The only reasonable place for such roads is over the railway, where practically all the difficulties as regards property and the use of the area covered have been fought out in years gone by. Such roads would merely be making use of space which might be referred to as being "in the air,"

The engineering problems in a task of this nature may be of .considerable magnitude, but are not such as would be likely to appal men who have achieved other feats Which at one time would have been regarded as well nigh impossible.

Consider what a wonderful vista of possibilities the carrying out of such a scheme would bring to our vision! Imagine beingable to run straight on to a trunk road at, say, St. Pancras, Charing Cross or Liverpool Street.

The scheme need not necessarilY he confined to the Metropolis. The arguments are almost equal in weight when considered in respect of others amongst our important cities, where the traffic is nearly as great as in London.

So far we have alluded to such over-the-railway roads as being useful links with the trunk roads, but, later on, as conditions justify and as finance permits, these links .might themselves be extended into trunk roads penetrating as far as the railways.

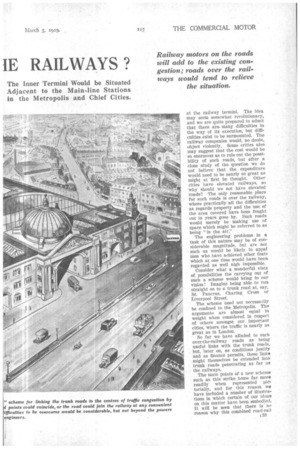

The main points of a new scheme such as this strike home far more readily when represented pictorially, and for this reason we have included a number of illustrations in which certain of our ideas on this matter have been embodied. It will be seen that there is no reason why this combined road-rail system should be inartistic or unharmonious,—in fact, the inner termini could easily be made quite pleasing. The ramps shown in our view of an important station could be utilized either for one-way or two-way traffic, according to the conditions. As depicted, vehicles are seen travelling in both directions.

Wheie tunnels are encountered there would be the option of raising the road over the tunnel or leaving the railway track for a short distance and rejoining where it emerged into the open. The latter procedure would only be necessary where the tunnel penetrated

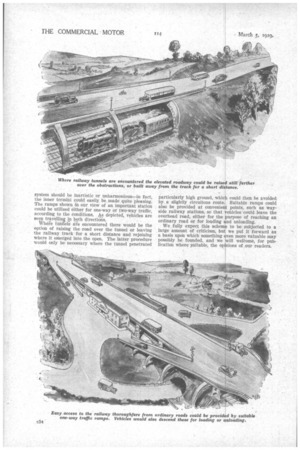

particularly high ground, which could then be avoided by a slightly circuitous route. Suitable ramps could also be provided at convenient points, such as wayside railway stations, so that vehicles could leave the overhead road, either for the purpose of reaching an ordinary road or for loading and unloading.

We fully expect this scheme to be subjected to a large amount of criticism, but we put it forward as a basis upon which something ven more valuable may possibly be founded, and we welcome, for pubilea ti on where suitable, the op mons of our readers.