UNRESOLVED QUESTIONS ON AMBULANCE DESIGN

Page 91

Page 92

Page 93

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

No change likely in use of dual-purpose types to provide basic service

by Ashley Taylor AMIRTE Assoc Inst T

MUN CI AL AND UTILMES

OVER the past few months there have been seemingly endless discussions on ambulance design, all springing from the almostin-confidence Ogle Report, which, although it runs to some 80 pages, in the opinion of many experts has failed to produce even the hoped-for answers about the emergency vehicle To give the matter its proper orientation, however, account must be taken of the fact that Ogle Design produced their report at the request of the GLC and the National Research Development Corporation. In Greater London there is wider economic use for what has come to be termed the emergency ambulance than under any other authority. However, something that fills the bill there may well not fit the pattern elsewhere.

My own feeling is that considering its scope the Ogle Report has had a disproportionate amount of publicity which may account for the idea in some people's minds that it publication foreshadows some general change in the pattern of British ambulances. Assuming the design to be acceptable for emergency services (and by no means everybody will agree with that) there still must be applied the same sort of economic principles as those governing general transport operations, different though the circumstances may be. Over the greater part of the country, territorial coverage must be the primary consideration and the expensive specialist vehicle does not fit particularly well into this scheme of things.

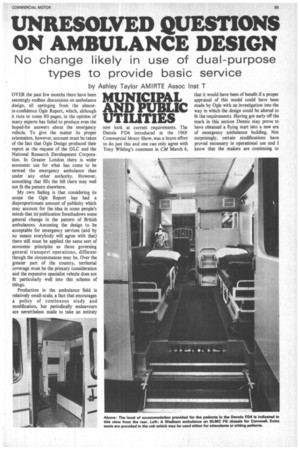

Production in the ambulance field is relatively small-scale, a fact that encourages a policy of continuous study and modification, but periodically endeavours are nevertheless made to take an entirely new look at current requirements. The Dennis FD4 introduced at the 1968 Commercial Motor Show, was a brave effort to do just this and one can only agree with Tony Wilding's comment in CM March 6, that it would have been of benefit if a proper appraisal of this model could have been made by Ogle with an investigation into the way in which the design could be altered to fit the requirements. Having got early off the mark in this section Dennis may prove to have obtained a flying start into a new era of emergency ambulance building. Not surprisingly, certain modifications have proved necessary in operational use and I know that the makers are continuing to obtain information from the counties of Surrey and Rutland on the subject. They have also made extensive inquiries among ambulance officers generally. Apart from analysing reports from these sources Dennis engineers have taken note of the Ogle study and the subsequent comments by health authorities and their officers.

In certain sections of the medical field there is deep concern over matters of equipment as well as over the general design of ambulances, but the bleak fact is that the emergency ambulance, as compared with the "treatment" ambulance, is not required in any great numbers. The home demand for what is strictly an emergency ambulance must be under 100 a year which, as there are few overseas sales for such vehicles, means a pretty expensive job. There are other good reasons why authorities prefer something more adaptable. Mr. W. H. Maycock, county ambulance officer for Cornwall, commented to me recently that it is essential in a rural county for each ambulance to be designed and equipped to deal with either an accident or emergency, or for taking one or more patients to hospital for treatment. Cornwall would, he said, find it virtually impossible to operate a two-tier service, one to deal with accidents and emergencies and another to convey other types of stretcher patients, because in practice the latter unit would more often than not be out on the road and nearer the incident than the former which if available would be standing in its garage, probably some considerable distance away. Cornwall's main treatment centres are at Plymouth and Truro so that cases frequently involve round trips of 50 miles or more.

Some of the various considerations that must influence the choice of specifications can be appreciated by examining the situation in Cornwall, with its narrow country roads and small seaside resorts. Here length and width of the vehicle are particularly important and a good turning circle is necessary. The BMC LD5W has proved satisfactory in this respect and, with a Wadhams purpose-built body, is stated to have filled all requirements. For replacements the county has chosen the BMC LDM with automatic gearbox. They have found that for emergency work the flashing blue lamp, while effective at night, is only partially successful by day, especially if conditions are sunny, so greater use is being made of the two-tone horn. In

summer, traffic conditions in the county are liable. to be difficult. Where congestion is holding up transport of an emergency

nature . the driver will use his telecommunications equipment to contact ambulance control who in turn will notify the police who will send out an escort car.

Land-Rovers in Lance

In Lancashire, a county of a completely different nature, the system is similarly single-tier. Details in the 1968 report of the service, the latest available at the time of writing, show a total of 300 ambulances of which nearly half are dual-purpose, mainly eight seats capable of adaptation to one stretcher /two seats. For the rest there are 118 with one fixed stretcher with loading gear, plus a seat for six that is adaptable for a second stretcher; then there are 33 with two bed units that are adaptable for two carry-in stretchers or 12 sitting cases, also two multi-purpose Land-Rover ambulances In a considerable number of cases Fernoflex cots or special trolleys are carried. With a fleet thus constituted there are available large sitting case ambulances for the urban areas and small units for rural use where filling the bigger type to capacity would involve longer rounds than desirable from the patients' point of view. When contemplating emergency vehicles, Mr. A. Orton, Lanes 'county ambulance organizer, told me, there is a tendency in many people's minds to assume that their main function is to deal with road accidents but the Lancashire report shows how far this is from being a fact. Among 62,736 cases handled by the emergency section in 1968 only 9,314 arose on the road, 24,000 were sudden illness and maternity cases, the remainder arising at home, in factories or collieries, in various public places and so on. In this county emergency-class calls represent only about 6 per cent of the total ambulance journeys. (There is, incidentally, nothing exceptional about this percentage as to the best of my knowledge the highest figure in the country is less than 10 per cent.) With 59,843 emergency journeys in Lanes in 1968 the average time taken to reach the case was 7.6min. which clearly shows the advantage of a good vehicle location network. In this connection ambulance officers have stressed to me that in many instances the gravity of a case cannot be known until experienced personnel arrive on the scene so that the adaptable type close to the spot has decided advantages over a specialist design that may have to be brought from a distance.

Effective usage of an ambulance varies from station to station. For this reason a "roundabout" plan is being followed in some places. This involves interchange of vehicles between stations where use is of varying intensity, the object being to achieve some equality of wear and tear over the entire fleet in the course of the rated vehicle life. This is a further argument in favour of a high degree of vehicle homogeneity.

There are in Britain over 140 authorities who purchase ambulances, among them, of course, being quite a number with definite emergency vehicle needs. In addition, some have regular need for transfer ambulances by which means patients are moved from one hospital to another. With the progress of medical science ever more advanced techniques are being employed but, since such 'equipment is expensive and the number of centres at which it can be installed is limited, movement of patients from hospital to hospital is necessary with fair frequency. Since the chances are that medical centres of the kind mentioned will be located in cities, and delays must be kept to a minimum, a good power-to-weight ratio and a high degree of manoeuvrability will be sought in the transfer unit. For these reasons the single-stretcher design based on conversions of the larger private cars finds favour. A few years ago forecasts were made that such units would be employed for motorway duties but the general experience has been that such requirements are best met by the general service, especially since more than one patient at a time is often involved. Whilst accidents are fewer on motorways, because of the higher speeds multiple casualties are much more likely.

Helicopters are sometimes used for the long-distance movement of patients in need of treatment that is to be procured at only a few places in the country but circumstances often necessitate road travel and the larger authorities will sometimes have a comfortable high-speed ambulance, capable of perhaps 100 mph, reserved for such duties.

The total of ambulances in operation in Great Britain may be taken as something under 7,000, not all of them attached to the official services since a number are the responsibility of voluntary bodies and industrial undertakings. Thus the gross annual purchases are not great. In view of the number of essential variations required to meet particular local conditions it is obvious that scope for anything in the nature of large-scale production is virtually non-existent, even allowing for a certain amount of overseas business. This latter is strictly limited and, to the best of my knowledge, Denmark has been the only European country to employ the typical British ambulance in the immediate past. Demands from abroad are largely concerned with utilitarian stretcher or cross-country designs. The versatile dual-purpose model is, of course, substantially an outcome of the National Health Sevice for which there is little call overseas. In many places outside Britain the provision of ambulances is in the hands of private contractors to whom the user must ultimately pay. This gives rise to the use of single-stretcher forms of the kind described earlier and it may mean greater potential for this class from the bodybuilders' point of view. Incidentally, one correspondent quotes the Ogle Report as saying that 70 per cent of the ambulance services in the United States are operated by undertakers, a statement that for obvious reasons has an ominous ring! However, perhaps it is not so alarming if one assumes that since American undertakers have apparently uprated themselves into morticians the term in question was meant to imply contractors.

Front-wheel possibilities

A good deal of hard thinking regarding future prospects is at present in progress among ambulance building specialists and will be interesting to see what is produced in time for next September's Commercial Motor Show. There have been some discussions on the general possibilities for ambulance work of a front-wheel-drive chassis, a feature to which the Ogle Report is committed. Reviewing the report, Tony Wilding said "a number of European front-wheel-drive vans are quoted as providing possibilities for conversion to ambulances. These are the Fiat 238. Citroen HY1500 Lancia Jolly and Alfa Romeo F12. But none of these has an engine or interior width big enough to meet the requirements quoted. And other European designs which could possibly be more suitable—such as the Hanomag F25/F35 range and the Saviem SB2 Trafic /Alfa Romeo F20—are not mentioned."

With bodybuilding as such there is no difficulty but a real problem that can be foreseen in relation to the general run of ambulances is that certain chassis which have been used for this purpose for a period of years are going out and the replacement models make a somewhat less suitable base for the job. With the choice narrowing there is, at the moment, some difficulty in seeing precisely what the future will hold. In this connection, by far the most important feature must be the suspension, for the elimination, or reduction, of road shocks is a vital matter. Variable suspension that will adjust to meet the different loadings involved with one stretcher, two stretchers, or different numbers of sitting patients, is most desirable.

I believe that this September most ambulance builders will not stick their necks out very far. The number of vehicles involved, as has already been emphasized, is such that they are likely to look for practical encouragement from prospective purchasers before launching any fundamen tal changes. While some few authorities may feel justified in trying out the occasional new emergency-type ambulance, despite its higher costs, stern economic considerations will rule out any wide-scale pioneering of fresh vehicles for the general service.

Within the scope of the emergency ambulance itelf what the bodybuilder can usefully incorporate is governed almost entirely by what the medical profession wishes to employ. Facilities must be available to enable first aid to be given and the patient sustained during the journey. Generally speaking, the object must be to transfer the sufferer as quickly as possible to hospital for further attention. In some cases more advanced equipment is essential, particularly for hospital board vehicles which may need to deal with cases of coronary thrombosis where the patient might be killed by being moved before receiving attention. By the use of a mobile coronary care unit, with a heart-care specialist in attendance, the heart movement may be stabilized before transfer to hospital. Similarly, ambulances equipped for surgery may be employed to deal with accidents where victims are trapped and an amputation must be performed on the spot.

Certain dimensional changes may prove necessary because space must be found to accommodate desired equipment but beyond this the matter of design is largely bound up with questions of transportation to which well-established rules must always apply.