BEDFORD M 9.3-TON 'GROSS 4X4 TRUCK

Page 58

Page 59

Page 60

Page 63

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

by Tony Wilding, MIMechE, MIRTE

WHEN the Bedford R-type 4 x 4 was tested by CM in 1962 various bits came adrift—such as the front bumper—and there was a transmission shaft failure when the vehicle was put through a severe appraisal exercise. Its successor, the Bedford M 4 x 4, which has just been announced by Vauxhall Motors, was put through the same type of test and, except for a small gearbox problem not associated with rough-road running, came through with flying colours.

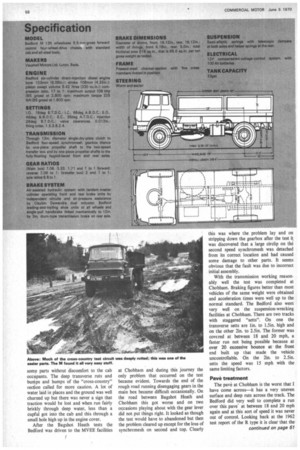

The test tracks of the Military Vehicles and Engineering Establishment (the new name for the FVRDE) were used for the main part of the test and the Bedford accepted a considerable amount of punishment without a murmur. The suspension of the new model proved to be particularly well designed and the 4 x 4 took the gradients of the Bagshot Heath Alpine circuit which go up to 1 in 2.75 with no trouble at all and managed a restart up the 1 in 3 slope at Chobham.

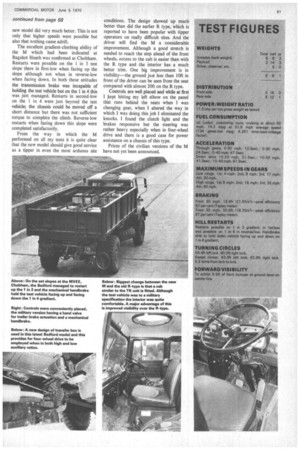

Braking and acceleration checks at the latter test site produced first-class results and on a 13.8 mile fuel consumption run on A30 the commendable figure of 14.2 mpg was returned when running at up to 40 mph. On the cross-country journey from Luton to Bagshot Heath which measured 49 miles and included heavy commuter traffic and winding, hilly roads, the test vehicle which was loaded to a gross weight of 9 tons 8.25 cwt. used fuel at the rate of 9.4 mpg when averaging just under 30 mph.

Differences Although tested with its military specification, the Bedford M will be available for civilian use in very much the same form, Most of the differences between the two types are confined to the electrical and fuel systems and the fitting of additional equipment such as a winch, trailer brake connection, hooks and so on, and apart from adding to the kerb weight these would not affect the sort of results obtained on this road.test.

The main difference between the new M and the old R type is the use cf a cab similar to the well-known Bedford TK unit. In its basic design concept the M follows the pattern of the R type. It has similar axles but increased in width and with stronger casings and the same main gearbox. For civilian use the chassis will be available with either the Bedford 330 Cu. in. diesel producing 107 bhp or the 300 Cu. in. 133 bhp petrol. For military application the 330 cu. in: multi-fuel engine will also be available. This is based on the diesel and was the actual unit fitted in the test vehicle. Gross output to the BS AU141 standard is 108 bhp at 2,800 rpm but this figure cannot be related directly to the other two quoted as AU141 figures are not available for them.

The four-speed synchromesh gearbox in the model drives through a single propeller

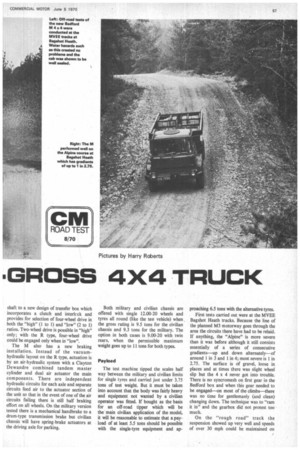

shaft to a new design of transfer box which incorporates a clutch and interlcck and provides for selection of four-wheel drive in both the "high" (1 to 1) and "low" (2 to 1) ratios. Two-wheel drive is possible in "high" only; with the R type, four-wheel drive could be engaged only when in "low".

The M also has a new braking installation. Instead of the vacuumhydraulic layout on the R type, actuation is by an air-hydraulic system with a Clayton Dewandre combined tandem master cylinder and dual air actuator the main components. There are independent hydraulic circuits for each axle and separate circuits feed air to the actuator section of the unit so that in the event of one of the air circuits failing there is still half braking effort on all wheels. On the military version tested there is a mechanical handbrake to a drum-type transmission brake but civilian chassis will have spring-brake actuators at the driving axle for parking. Both military and civilian chassis are offered with single 12.00-20 wheels and tyres all round (like the test vehicle) when , the gross rating is 9.5 tons for the civilian chassis and 9.3 tons for the military. The option in both cases is 9.00-20 with twin rears, when the permissible maximum weight goes up to 11 tons for both types.

Payload The test machine tipped the scales half way between the military and civilian limits for single tyres and carried just under 3.75 tons of test weight. But it must be taken into account that the body was fairly heavy and equipment not wanted by a civilian operator was fitted. If bought as the basis for an off-road tipper which will be the main civilian application of the model, it will be reasonable to estimate that a payload of at least 5.5 tons should be possible with the single-tyre equipment and ap proaching 6.5 tons with the alternative tyres.

First tests carried out were at the MVEE Bagshot Heath tracks. Because the line of the planned M3 motorway goes through the area the circuits there have had to be relaid. If anything, the "Alpine" is more severe than it was before although it still consists essentially of a series of consecutive gradients—up and down alternately—of around 1 in 3 and 1 in 4; most severe is 1 in 2.75. The surface is of gravel, loose in places and at times there was slight wheel slip but the 4 x 4 never got into trouble. There is no syncromesh on first gear in the Bedford box and when this gear needed to be engaged—on most of the climbs—there was no time for gentlemanly (and clean) changing down. The technique was to "ram it in" and the gearbox did not protest too • much.

On the "rough road" track the suspension showed up very well and speeds of over 30 mph could be maintained on some parts without discomfort to the cab occupants. The deep transverse ruts and bunips and humps of the "cross-country" secfion called for more caution. A lot of water laid in places and the ground was well churned up but there was never a sign that traction would be lost and when run fairly briskly through deep water, less than a cupful got into the cab and this through a small hole high up in the engine cover.

After the Bagshot Heath tests the Bedford was driven to the MVEE facilities at Chobham and during this journey the only problem that occurred on the test became evident. Towards the end of the rough road running disengaging gears in the main box became difficult occasionally. On the road between Bagshot Heath and Chobham this got worse and on two oecasions playing about with the gear lever did not put things right. It looked as though the test would have to abandoned but then the problem cleared up except for the loss of synchromesh on second and top. Clearly this was where the problem lay and on stripping down the gearbox after the test was discovered that a large circlip on the second speed synchromesh was detached from its correct location and had caused some damage to other parts. It seems obvious that the fault was due to incorrect initial assembly.

With the transmission working reasonably well the test was completed at Chobham. Braking figures better than most vehicles of the same weight were obtained and acceleration times were well up to the normal standard. The Bedford also went very well on the suspension-wrecking facilities at Chobham. There are two tracks with staggered "setts". On one the transverse setts are lin. to 1.51n. high and on the other 2in. to 2.5in. The former was coy( red at between 18 and 20 mph, a faster run not being possible because at over 20 excessive bounce at the front end built up that made the vehicle uncontrollable. On the 2in. to 2.5in. setts the speed was 15 mph with the same limiting factors.

Pave treatment The pave at Chobham is the worst that I have come across—it has a very uneven surface and deep ruts across the track. The Bedford did very well to complete a run over this pave' at between 18 and 20 mph again and at this sort of speed it was never out of control. Looking back at the 1962 test report of the R type it is clear that the new model did very much better. This is not only that higher speeds were possible but also that nothing came adrift.

The excellent gradient-climbing ability of the M which had been indicated at Bagshot Heath was confirmed at Chobham. Restarts were possible on the 1 in 3 test slope there in first-low when facing up the slope although not when in reverse-low when facing down. In both these attitudes the transmission brake was incapable of holding the test vehicle but on the I in 4 this was just managed. Restarts in second-low on the 1 in 4 were just beyond the test vehicle; the chassis could be moved off a short distance but there was not sufficient torque to complete the climb. Reverse-low restarts when facing down this slope were completed satisfactorily.

From the way in which the M performed on all my tests it is quite clear that the new model should give good service as a tipper in even the most arduous site conditions. The design showed up much better than did the earlier R type, which is reported to have been popular with tipper operators on really difficult sites. And the driver will find the M a considerable improvement. Although a good stretch is needed to reach the step ahead of the front wheels, access to the cab is easier than with the R type and the interior has a much better trim. One big improvement is in visibility—the ground just less than 10ft in front of the driver can be seen from the seat compared with almost 20ft on the R type.

Controls are well placed and while at first I kept hitting my left elbow on the panel that runs behind the seats when I was changing gear, when I altered the way in which I was doing this job I eliminated the knocks. I found the clutch light and the brakes responsive but the steering was rather heavy especially when in four-wheel drive and there is a good case for power assistance on a chassis of this type.

Prices of the civilian versions of the M have not yet been announced.