Fast, Luxurious, Economical Travel

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

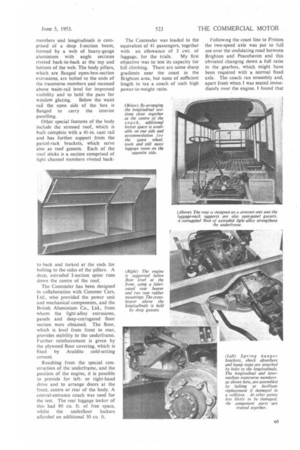

Chassisless Coach with Standard Power and Transmission Units is Lighter than Orthodox Design and Provides Higher Performance : Longitudinal Members are Arranged for Capacious Luggage Lockers at the Sides and Rear

By Laurence J. Cotton

M.I.R.T.E.

WEIGHING only 41 tons when ready for the road, the Harrington Contender 41seater coach, 30 ft. long and 8 ft. wide, has exceptional performance and, with its comfortable seats and smooth suspension, the passenger is afforded fast, luxurious travel.

Although putting the engine below floor level has enabled 40 or more passengers to be carried on longdistance coaches, the space occupied by an amidship-mounted power unit usually restricts the size and number of luggage lockers. The Harrington product escapes this criticism, because, with the engine below floor level ahead of the front axle and chassisless construction, up to 110 Cu. ft. of luggage can be accommodated in lockers at the sides and rear, whilst the parcels racks afford an additional 40 Cu. ft. for small packages, coats and hats.

There are main members in the integrally constructed underframe for mounting the engine, transmission and springs, but in its general conception the Harrington is a chassisless vehicle, with longitudinal stiffness provided by the floor, sides and roof of the body. The underframe longitudinals are sectioned by six transverse members, of varying depth, placed to coincide with the main body pillars.

Spacing of the longitudinals is controlled by the position of the engine mounting points, brake servo motor, propeller-shaft support bearings, side luggage lockers and rearspring hanger brackets.

The Commer six-cylindered petrol engine, which develops 109 b.h.p. at o2 3,000 r.p.m., is installed horizontally and employs standard bearers and mounting arrangements. At the front, the standard tubular steel bearer is retained, this and a fabricated rear bearer being bolted to the longitudinals ahead of the axle. In effect, the front axle of the Harrington coach is set farther back in comparison with the Avenger, .enabling the power unit to be mounted lower and providing room for a forward entrance, if required.

The clutch and gearbox are conventionally attached to the engine, with the gear selector and handbrake lever remotely mounted on a bracket supported from the cylinder

block casting. A three-piece propeller shaft is used. This has Layrub

couplings immediately behind the gearbox and at the axle.

An Eaton two-speed axle with electrical shift was supplied on the test vehicle, but a single-ratio axle is also available. The Harrington coaches operated by B.O.A.C. have a fixed ratio of 6.0 to I.

Conventional brackets a r e employed for attaching the springs, steering box and shock absorbers to the underfrarne, and for the brake servo, which is supported within the longitudinals near the front axle. With a detachable front panel and floor traps over the engine and running units, exceptional accessibility is afforded for inspection, adjustment or the replacement of parts.

Each of the six transverse members and longitudinals is comprised of a deep I-section beam, formed by a web of heavy-gauge aluminium with angle sections riveted back-to-back at the top and bottom of the web. The body pillars, which are flanged open-box-section extrusions, are bolted to the ends of the transverse members and recessed above waist-rail level for improved visibility and to hold the pans for window glazing. Below the waist rail the open side of the box is flanged to carry the interior panelling.

Other special features of the body include the stressed roof, which is built complete with a 4I-in, cant rail and has further support from the parcel-rack brackets, which serve also as roof gussets. Each of the roof sticks is a section comprised of light channel members riveted back to-back and forked at the ends for bolting to the sides of the pillars. A deep, extruded Lsection spine runs down the centre of the roof.

The Contender has been designed in collaboration with Commer Cars, Ltd., who provided the power unit and mechanical components, and the British Aluminium Co., Ltd., from whom the light-alloy extrusions, panels and deep-corrugated floor section were obtained. The floor, which is level from front to rear, provides stability to the underframe. Further reinforcement is given by the plywood floor covering, which is fixed by Araldite cold-setting cement.

Resulting from the special construction of the underframe, and the position of the engine, it is possible to provide for leftor right-hand drive and to arrange doors at the front, centre or rear of the body. A central-entrance coach was used for the test. The rear luggage locker of this had 80 Cu. ft. of free space, whilst the underfloor lockers afforded an additional 30 Cuft. The Contender was loaded to the equivalent of 41 passengers, together with an allowance of 3 cwt. of luggage, for the trials. My first objective was to test its capacity for hill climbing. There are some sharp gradients near the coast in the Brighton area, but none of sufficient length to tax a coach of such high power-to-weight ratio. Following the coast line to Friston the two-speed axle was put to full use over the undulating road between Brighton and Peacehaven and this obviated changing down a full ratio in the gearbox, which might have been required with a normal fixed axle. The coach ran smoothly and, apart from when I was seated immediately over the engine. I found that

the design was commendable for

quiet operation. At the front the fan noise is noticeable at high engine speed, but the usual gearbox whine in the indirect ratios is not so pronounced.

In a vehicle built expressly for coach work it is preferable for the passengers to be seated fairly high, so that they can see over the hedges so typical of the British countryside. The arrangement of the Contender coach is ideal for passenger visibility, in addition to providing good seat positions with adequate leg room. The narrow pillars are well spaced to prevent blind spots and the depth and width of the windows afford an unrestricted view.

I took control at Friston and headed the coach inland towards Polegate and Alfriston, in readiness for the first hill climb. Driving a coach of 8-ft. width through narrow winding country roads required care, and I appreciated the general handling characteristics and liveliness of the vehicle.

Caution was again required when negotiating Alfriston, where, in addition to a narrow thoroughfare, D4

there were parked vehicles and overhanging signs. Many operators have criticized the " stepped" screen of the Contender Mark I model because of its bus-like appearance, but its value is appreciated when negotiating confined spaces. The near-view screen should also be advantageous for driving in fog.

Easy Start on 1 in 6

The test hill at Alfriston was about half a mile long, with an average gradient of 1 in 9 and a major section of 1 in 61 where second gear was used in the first non-stop climb. In a subsequent trial, when starting from rest at the severest point, the coach moved off quite smoothly in high first gear with a part throttle opening. There was no overheating, the water temperature rising . from 175-185 degrees F. in two climbs and the engine-oil temperature was moderate. The ambient reading was 62 degrees F.

A consumption test was made over a 20-mile out-and-return course on the London road, 'and here the Contender showed its form by making a fuel return of 11.82 m.p.g. at an average speed of just over 33 m.p.h. Almost 12 m.p.g. for a 41seater petrol-engined coach operating a fast schedule is unusually economical and this is one of the major, advantages derived from reduced running weight. Other advantages lie in its high acceleration rate and the reduction of wear of the brake friction material.

Apart from using axles suitable for an 8-ft. wide body, the brake equipment and gear ratios are identical to those of the Commer Avenger, which is known for its high performance. With the reduced weight of the Contender, the braking effort was more notable, and forceful application of the lever or pedal caused wheel locking.

Stopping distances of 33 ft. from 20 m.p.h. and 68 ft. from 30 m.p.h., although good, are hardly indicative of the true retardation rate, which could not be assessed because of the limit imposed by road adhesion. A sharp application of the hand brake sent the Tapley drum spinning smartly, to register 50 per cent., which must be a record for any commercial vehicle. The brake tests were conducted on the Marine Parade at Brighton where, because of the unusual degree of retardation, all trials had to be made on the crown of the road in order to reduce the tendency to wheel locking.

From rest to 30 m.p.h. in 20 see. is acknowledged as exceptional acceleration for a 40-seater coach, yet this standard was well exceeded by the Harrington product in both high and low ratios of the axle. In low ratio it took 16.6 sec. and with the higher ratio in use it occupied 18.2 sec. I was satisfied in all respects that the Contender has the requisite performance and comfort for luxury travel and would be an economical acquisition where a petrol-engined fleet is operated. No special effort is required in operating its controls and the steering is pleasantly light.