"0

Page 62

Page 63

Page 64

Page 67

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

'e more, and how, much it is!"

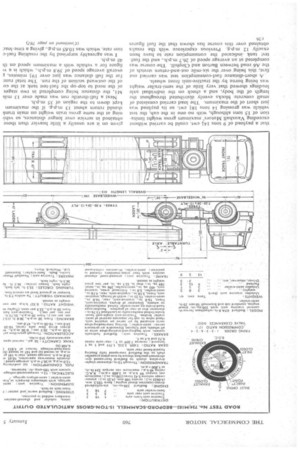

ON November3, 1961, we forecast that the enlarged version of the Bedford 300-cu.-in. diesel engine, which at that time had become available in the SB passenger chassis, would probably be offered as optional equipment in various Bedford goods models, and on December 8, 1961, we were able to confirm this news, Shortly after the official announcement that this new unit would be available in 7and 71-ton load-carriers and in 10and 12-ton tractive units, a 10-ton prime mover powered by the new 330 engine was offered to me for test in conjunction with a Scammelf 10-ton 25-ft. semi-trailer.

Tested at a gross train weight of 15 •tons 2 cwt., this Bedford-Scammell articulated outfit put up a good average performance for this class of vehicle whilst, because the prime mover was from the TK range, driving conditions and the general standard of comfort and safety were far above average. Unfortunately, I had not. previously tested one of these TK 10-ton tractive units powered by the original 300-cu.-in. engine, so cannot make direct comparisons between the performance of that engine and the new enlarged version.

However, tests made in 1960 with two Bedford S-types converted to six-wheelers and running at approximately 15 tons gross weight show that the performance of this latest articulated outfit at the same weight is very nearly the same as the average of the two performances realized by the two six-wheelers. Therefore, allowing for the fact that. for some inexplicable reason, some TK models have been shown to be very slightly less economical weight-for-weight and engine-for-engine than preceding S-type vehicles, it is clear that use of this larger engine does not involve any sacrifice in fuel saving, whilst the extra engine power should have a decidedly, advantageous effect on vehicle liveliness.

The 330-cu.-in. engine differs mainly from the earlier 300-cu.-in. unit in its 10 per cent. greater cylinder capacity. made possible by the use of Laystall Cromard thin-wall cylinder liners, by which means the displacement has been increased from 4.927 litres to 5.42 litres. In addition to giving the increase in cylinder capacity, these Cromard liners will, of course, show greatly increased bore life, which means not only longer operational intervals between liner

c14

but also low oil consumption over longer periods. the introduction of these new liners various other :tat alterations were made to the engine, including af shorter, but larger-diameter, cylinder-head studs tilled types of gasket, all with the object of improvet life, whilst the maximum governed speed when with no load applied has been increased from ).m. to 3,000 r.p.m., the comparable gross power of the two engines at these speeds being 97 b.h.p. .5 b.h.p.

very simply, the Bedford engineers have been able a an extra 10 b.h.p. (net) at 2,600 r.p.m. (99 b.h.p. d with 89 b.h.p.) and an additional 24 lb.-ft. torque for an extra cost to the customer of a mere £10. torque figures of the two engines are 210 lb.-ft. lb,-ft_ and the torque peak of the 330 occurs at rm. compared with 1,400 r.p.m. in the case of the Lne. Furthermore, the torque of the 330 between and 2,450 r.p.m. is greater than the maximum .gure of the smaller engine.

ew 330 engine is available as optional equipment in I J6L normal-control 7-tormers, KFS, KFL and irward-control 7-tonners, and the KFA forward10-ton tractive unit. Further to this, the engine has been adopted as standard equipment in KGL and KGT forward-control 74-tonners, the K(3A forward-control 12-ton tractive unit and the SB passenger chassis. The 300-cu.-in. engine remains in production for the time being. but, if, as seems likely, the majority of future orders are for the larger engine where this is an option, the 300 unit might eventually be dropped.

The use of Laystall Cromard liners was at the same time applied to the 200-cu.-in. engine so that there now is a 220-cu.-in. (3.61-litre) engine available as optional equipment in lighter Bedfords, thus enabling Vauxhall's to offer more-powerful diesel engines of their own make in all Bedford vehicles of from 3 tons capacity upwards.

Use of the new engine in the 10-ton tractive unit has not involved any other modifications to the vehicle specification. The same 12-in.-diameter clutch and four-speed wide-ratio synchromesh gearbox are retained, and there is the same choice of singleor two-speed axles, the single-speed unit having a ratio of 6.8 to 1, whilst the two-speed equipment give S ratios of 6.4 and 8.72 to 1.

Air-pressure Servo

Standard tyres are 7.50-20 (12-ply) and the hydraulic braking system, the total frictional area of which is 493 sq. in., is air-pressure boosted in the case of dieselengined models, and vacuum-boosted when a petrol engine is fitted, although for ease of inter-working a vacuumhydraulic system is available on diesel models. In all cases the hand-brake acts on a Lockheed 13.76-in. diameter disc located at the rear of the gearbox, lighter Bedford TKs having a drum transmission brake.

The tractive unit has a wheelbase of 8 ft., and the chassisframe side members are 0.22-in.-thick pressings with a maximum depth of 8.44 in. and 2.5-in, flanges. The model is suitable for use with all types of automatic or fifth-wheel coupling gear and listed optional equipment includes fivespeed constant-mesh gearbox, heavy-duty clutch, three-piece wheels, and 8.25-20 (14-ply) or 9.00-20 (12-ply) tyres. Unlike TK load carriers, the tractive units do not have flashing direction indicators as standard equipment, but these can be fitted and, indeed, were on the test vehicle.

The semi-trailer provided for my test was the one with which the tractive unit will be operating when it joins the Bedford demonstration fleet shortly. It was a standard Scarnmell 25-ft.-long 10-ton unit with double-drop-side body and 9,00-20 (12-ply) tyre equipment.

Its unladen weight was 2 tons 5+ cwt. and as the kerb weight of the tractive unit was 3 tons 4cwt. this meant c25

that a payload of 9 tons 141 cwt. could be carried without exceeding Vauxhall Motors' maximum gross weight limitation of 15 tons although, with no one in the cab, the test vehicle was grossing 14 tons 181 cwt. so its payload was just short of the maximum. The load carried consisted of small concrete blocks evenly distributed throughout the length of the body, and a check on the individual axle loadings showed that very little of the semi-trailer weight was being borne by the tractive-unit front wheels.

A Shortdistance-fuel-consutnption test was carried out first,this being over thesix-mile out-and-return stretch of the A6'road•between Barton and Clophill. The course was completed at an average speed of 26.7 m.p.h., and the fueltest tank ,indicated the consumption rate to have been exactly 12 m.p.g. Previous experience with the results obtained over this course has shown that the fuel figures

c26 given on it are usually a little heavier than those obtained in service over longer distances, so vehit fling at the same gross train weight on main trunl should return about 13 m.p.g. if the maximum kept down to the region of 35 m.p.h.

Next a full-throttle run was made over 13 milf MI, the distance being completed in two stages of the need to top-up the fuel-test tank at the co of the outward section of the run. The total rum: for the full distance was just over 19; minutes, overall average speed of 39.8 m.p.h., which is a vi figure for a vehicle with a maximum speed on th 48 m.p.h.

I was agreeably surprised by the resulting fuel-c tion rate, which was 10.65 m.p.g., giving a time-loae

f 6,408. The outfit handled in a very stable fashion mum speed and was generally quiet, although a amount of propeller-shaft vibration could be heard t 50 m.p.h. when over-running on down grades. fuel-consumption rates show that the TK tractive auld definitely be an economical proposition to on long-distance trunking runs in this country, parif maximum use can be made of the-growing netmotorways. Although by no means over-powered, outfit has a useful maximum speed and a sufficiently read of gear ratios to enable speed to be kept up areas.

wing these fuel runs braking tests were conducted, ie revealed a certain amount of braking unbalance the tractive unit and the semi-trailer, as braking no means smooth when stopping from both 20 Lnd 30 m.p.h. and it was obvious that the semirakes were not doing their fair share of the work, theless, despite considerable bucking of the tractive h time the brakes were applied, quite reasonable distances were obtained, the outfit coming to rest / m.p.h. in almost 12 ft. less than the distance by an S-type tractive unit tested in conjunction carnmell 10-ton semi-trailer in August, 1956. When from each speed all the wheels of the tractive unit accompanied by a slight pulling to the right, but as was dry there was no danger of the outfit jack

dation figures were then taken with the tractive-unit ake from 20 m.p.h. and sharp application of this :stilted in an average maximum Tapley meter read3.5 per cent., which I consider to be an excellent 3nly slight judder was noticed, and that merely for few feet before coming to rest.

th most current articulated vehicles, the semi-trailer can be applied separately by means of a hand In the cab. Use of this control alone from 20 m.p.h. in retardation-meter readings averaging 17.5 per e relatively low value of this figure serving to submy opinion that the semi-trailer brakes of the test vere not quite as powerful as they might have been, ame stretch of level, concrete-surfaced road was r acceleration tests. Low axle ratio was used aut these tests, second, third and top gears being ing the standing-start tests. Although not spectacuacceleration times recorded were quite adequate: celeration can be obtained with vehicles with bigger but these cost more initially. Engine and transsmoothness was most marked during the direct Fast Climb :r power tests were made on the 4-mi1e-long Bison average gradient of which is 1 in 104. A fast climb gradient indicated the advantage of the additional

I this 330 engine, the ascent taking only 54 minutes, less than 4 minute more than that required by a ned TK 7-tonner tested in 1960, at a gross weight Rader 101 tons.

ainimum speed recorded during the climb was 5 and the lowest gear-ratio combination used was tigh, this being needed for 1 minute 57 seconds. of the TK's remote cooling-system header tank, no naperatures could be taken to check engine-cooling but the instrument-panel temperature-gauge ardly rose at all during the ascent. Leek for fade resistance I coasted the Bedford II down Bison Hill in neutral, engaging top gear ying full throttle whilst still keeping the foot-brake applied hard on the lower slopes of the hill where the gradient is not so severe. This descent lasted 2 minutes 24 seconds, and a full-pressure stop at the bottom of the hill produced a Tapley-meter reading of 60 per cent., indicating a reduction in maximum efficiency through fade of only 13.5 per cent.

Thus, fade resistance was shown to be good, the tractiveunit brakes still being powerful enough to lock all the wheels despite voluminous quantities of smoke issuing from all the tractive-unit brakes and from the off-side semi-trailer brakes also..

During this descent I noticed that I was having to apply an increasingly greater load to the brake pedal to maintain retardation, but at the end of the test it was found that pedal travel had not measurably increased. The " hardness " of the pedal did not altogether surprise me, as the brakes on this outfit were not by any means light to operate even with cold drums, presumably because of the semitrailer brakes.

I then returned the outfit up the hill and stopped it on the steepest section, where the gradient is I in 61. The tractive-unit hand-brake held the vehicle comfortably without any undue effort being necessary on the lever, but the semi-trailer brakes were not powerful enough to restrain the outfit from rolling back down the hill, either when applied by the control in the cab (which operates the air servo working the semi-trailer brakes through the coupling linkage) or when applied by means of the ratchet-type lever located at the front of the semi-trailer. After these hillholding tests, an easy bottom-high restart was made without any clutch slip or tractive-unit bucking.

Quiet and Comfortable Taken generally, this Bedford-Scammell outfit was an extremely pleasant one to drive, being quiet and comfortable at all times and only the brakes being heavy to operate, and then only when above-normal retardation became necessary. This new engine, the idling of which was noted to be a little on the rough side, sounds quieter than the 300 unit, but this might be just that the note is deeper. Certainly the engine pulls well and was observed to be completely smoke-free under all test conditions.

As remarked before in connection with Bedford TK models, the gear-change action of this tractive unit was a bit vague and sloppy, but I was relieved to find that minor changes to the air-pressure-actuated two-speed-axle change mechanism have resulted in this being very much more definite than it had been up till recently, permitting very quick, positive changes both up and down with hardly any fear of a change being "missed." Despite its short wheelbase, the tractive unit rode well.

I hardly need comment further about the TK, it having one of the most driver-conscious cabs ever to have been designed for a high-production commercial vehicle anywhere in the world, even the headlamps—although perfectly standard Lucas F700 equipment—seeming to give above-average illumination of the road ahead, an impression possibly caused by the large, deep windscreens.

The Bedford KFA 10-ton tractive unit with 330-cu.-in. diesel engine and standard cab, but without coupling gear, costs £1,145 when specified with the single-speed axle, the two-speed axle adding £95 to this basic price. The optional 13-in.-diameter clutch is listed at £2 10s. extra, whilst the engine can be obtained with a mechanical fuel-pump governor (instead of the standard vacuum governor), and this costs £19 10s. extra. Specification of vacuum servo braking in the case of diesel-engined tractive unit adds nothing to the basic price, but an upright-vacuum servo system instead of the suspended-vacuum equipment can be specified at an extra cost of £3 10s.