Snowed under with work in a winter wonderland

Page 65

Page 66

Page 67

Page 68

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

CM's Lorry Driver of the Year wanted a taste of hauling in Arctic conditions. Thanks to Michelin and Salm& he got it. David Wilcox was with him, in Sweden

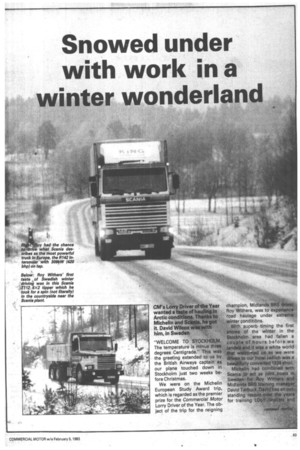

"WELCOME TO STOCKHOLM. The temperature is minus three degrees Centigrade." This was the greeting extended to us by the British Airways captain as our plane touched down in Stockholm just two weeks before Christmas.

We were on the Michelin European Study Award trip, which is regarded as the premier prize for the Commercial Motor Lorry Driver of the Year. The object of the trip for the reigning champion, Midlands BR Roy Withers, was to experience road haulage under extreme winter conditibns.

With superb timing the first snows of the winter in the Stockholm area had fallen a couple of hours before we landed and it was a white world that welcomed us as we were driven to our hotet4which was a beautifully converted 1924 ship).

Michelin had combined with Scania to act as joint hosts in Sweden for Roy Withers and MidlandS EMS training manager David Tarbuck. David has an outstanding record over the years for training LOoY finalists and

Roy headed the Midlands BRS drivers who took three out of the eight classes at the LDoY finals last September.

When he is not winning driving competitions (he was also champion in 1977), Roy Withers drives a Ford Transcontinental artic, picking up car components in the West Midlands area and delivering them to the Birmingham BRS depot for consolidation and subsequent trunking to Ford plants around the country. All very different from what he was about to see during his week in Sweden.

Our first port of call was the Scania plant at Sodertalje, 25km (16 miles) southwest of Stockholm. Although Scania came to the UK as recently as the mid-Sixties, the marque has a long history in Sweden thanks to its Vabis connections — the first Vabis lorry was built in 1903.

Following the merger with Saab in 1968 the Scania division emerged as the largest of the three divisions; the other two manufacture Saab cars and aeroplanes.

Scania and Volvo are neck and neck in their share of the Swedish home market for lorries over 10 tonnes gvw and between them have virtual total dominance; they each have about 48 per cent. This leaves a miserly four per cent for imported lorries over 10 tonnes, which is mainly accounted for by Mercedes-Benz and Ford.

Despite this strong domestic market position, Scania cannot afford to rest on its laurels. The Swedish market is too small. In fact, Scania exports no less than 88 per cent of its production and Iraq is the largest market, followed by Sweden itself and then Brazil, Italy and France. Great Britain ranked ninth in this league in 1981 but 1982 was a good year for Scania GB and if this progress is maintained then Great Britain will be firmly established in the top five overseas markets for Scania.

Scania's main plant at SOdertalje employs 7,000 people and is one of the town's two main claims to fame — the other is that it was Bjorn Borg's home town before he moved to Monte Carlo.

After our tour round the plant Roy Withers had his first chance to sample the Swedish winter driving conditions, starting with a Scania T112 rigid 6x2. The T prefix indicates that this was the bonneted version and it also had the intercooled engine, launched just a couple of months earlier.

The addition of air-to-air charge-cooling raises the power output of the 11-litre engine from 224kW (305 bhp) to 245kW (333 bhp), giving a considerable surplus of power in the 6 x 2 tipper that was laden to its maximum gvw of 22.5 tonnes.

Heading out into the country south of Sodertalje on the snowcovered roads both Roy and David Tarbuck expressed an instant liking for this bonneted cab, commenting on the low interior noise level and the roomier feel because of the less intrusive engine position. Bonneted cabs are relatively common in Sweden where there are more generous length limits.

Roy next tried the top model in the Scania range, the R142 Intercooler in 6x2 guise with tilt bodywork. The intercooler version of the 14-litre V8 turbocharged engine has an output of 309kW (420 bhp}, making this the most powerful standard production lorry in Europe.

This sort of output is obviously designed with Sweden's 51.4 tonne gtw limit in mind and the 6 x 2 that Roy drove was really the front end of a maximum weight drawbar outfit.

As a three-axle rigid it was restricted to just 22.5 tonnes gvw giving a power-to-weight ratio of 13.7kW per tonne (18.6 bhp per tonne).

With so much power on tap, plus the complications of lefthand drive and snow-covered roads, Roy had a lot to contend with but his confidence was boosted when the Scania test driver told him to stamp on the brakes and see what happened. The R142 was fitted with ABS anti-lock braking and it pulled up straight without drama.

When we in Britain have only just got the go-ahead for 38-tonners and are restricted to 15.5m artics and 18m drawbars, how In Sweden accept 51.4-tonners at measure 24m in either artic drawbar form? Our Swedish msts from Michelin and Scania :plained that Sweden is a long iuntry (1,000 miles from top to )ttom) covering twice the area

Great Britain but with a )pulation of just 8.3 million — 3ry similar to Greater London. With such mileages to be coyed on the long north-south 3u1, 38-tonners would be a terFic disadvantage. And with mrse population and excellent Jality roads long and heavy lotas are not too intrusive or )cially unacceptable.

Just over a year ago Sweden ung even further away from me rest of Europe by extending s width limit for lorries from ,5m to 2.6m. There are also roposals to further increase the maximum weight to 60 tonnes. The following morning saw us n an internal flight heading orthwards 800km (500 miles) to Luleg, a coastal town at the head of the Baltic. Scania has a heavy pressing plant here making chassis members.

Luleg is about 120km (75 miles) short of the Arctic Circle and there was no forgetting the fact. As we left Luleg Airport it was 10.30 am but the sun had been up for only an hour and was barely above the horizon. The mercury was threatening to leave the thermometer altogether; it was down to minus 24 degrees Centigrade.

Across the road from the airport was a Lulefrakt depot. Lulefrakt is one of the 250 or so "central trucking agencies" in Sweden; each is a group of small haulage companies (mainly owner-drivers) who cooperate to share depots and cen tralise administration.

Waiting for us in the yard was owner-driver Ragnar Akerstrom with his Scania R142 timbercarrying drawbar rig. The outfit was to the maximum 24m but even then Ragnar wanted every centimetre and it was only a day cab on the 6x2. A Hiab crane with a special log-handling attachment was mounted at the rear of the rigid.

Ragnar worked on contract to a paper mill in Piteg, about 40km (25 miles) down the coast from Lula, picking up logs from the timber forests and delivering them to the papermill for pulping. He has been doing this for 28 years.

Roy climbed up into the 142's cab alongside Ragnar and with the rest of our little entourage following in two cars we set off in search of the forests.

We travelled inland and northwards for about 40km (25 miles) before turning off down a small track into the forest. This got narrower and narrower and the big Scania disappeared in a cloud of snow that it kicked up; the snow was light and almost completely dry. It was only the compressed snow and frozen ground that made the track usable; underneath it was just sand and if the Scania had gone the same way in summer it would have sunk in.

Sticks planted in the banks of snow marked the edge of the track and as we followed the Scania the advantage of its drawbar configuration was plain to see. Despite its 24m length Ragnar was able to keep the outfit safely on the narrow track thanks to very little cut-in from the trailer.

About 30km (19 miles) into the forest we came to a clearing with a pile of logs on each side of the track, Two off-road logging vehicles were parked up and four fitters were replacing a gudgeon pin on a crane attachment. A fire was lit to heat up the gudgeon pin and keep the men a little warmer.

The atmosphere was magical. Although it was midday the sun was still just an orange ball on the horizon. The forest was empty and silent apart from the sound of the fitters hammering at the gudgeon pin.

Ragnar lowered the lifting rear axle on the Scania to accept the payload and with the engine ticking over to power the Hiab started loading the logs. Even if they do not have any power-driven accessories it is standard practice in the Swedish winter to leave engines ticking over for long periods — it keeps the oil mobile and the cab warm. Most cars and lorries have thermostatic electric heaters built into their cooling systems and these are plugged into the mains supply overnight. Suitable coinoperated power points are provided in many car parks.

Ragnar worked fast in the biting cold and loaded the vehicle to its gross weight with around 35 tonnes of timber.

Ragnar had bought his Scania R142 nine months earlier in March before the lntercooler version had been launched and so it had the non-charge-cooled engine developing 285kW (388 bhp). In this short time the Scania had already covered 96,000km (60,000 miles). Ragnar normally keeps his lorries for 600,000km (370,000 miles) or about five years before selling them, usually in Finland. He nodded eagerly when I asked him via our interpreter if he intended to buy an Intercooler R142 next.

This current R142 is averaging about 451/100km (6.3 mpg) and, more importantly, has been totally reliable. A breakdown in these lonely forests in sub-zero temperatures is a serious mat ter. Ragnar uses cb radio to keep in touch with other drivers in the forests and to warn them he is on a particular track so that he does not meet them coming in the opposite direction.

The compacted snow on the track glistened in the Scania's headlights as Ragnar smoothly piloted the 51.4 tonnes of lorry back out of the forest on the way to the papermill. He was using studded tyres on the steering axle, Michelin M + S on the drive axle and Michelin XZY on the trailer. The choice of tyres for winter in Sweden is rather more important than in the UK and most lorries and cars have two sets of tyres for winter and summer.

Ragnar's Scania had a set of snow chains hanging from the chassis but conditions were just good enough to get by without them. Another piece of tractionimproving equipment that Ragnar had fitted to the Scania was Robson Drive. This comprises a small metallic-toothed wheel that is lowered (via the same system that operates the lifting axle) so that it is effectively "wedged" between the drive axle and trailing axle. Thus, the 6 x 2 temporarily becomes a 6x4, giving additional traction.

The Robson Drive can be used for short periods only (such as when driving out of awkward spots) because its toothed wheel is none too kind to the tyres.

As we progressed down the track the automatic tensioning device light flashed occasionally as the logs settled and more tension was applied. Two spotlights on the Scania's roof were angled towards the edge of the forest and Ragnar explained that these were to spot elk or reindeer.

Elk cause a considerable number of road accidents in Sweden; they can be as big as a horse and weigh around half a tonne. Running into them with a car can be particularly dangerous because their long thin legs break and the torso comes up the bonnet and through the windscreen with predictably disastrous results.

We arrived at the Pitei papermill 120km (75 miles) away at 4.45 pm and Ragnar first pulled into the weighing station so that the timber could be found in order to calculate Ragnar's payment. In fact, the load is not weighed; its dimensions are measured because the logs' weight is too dependent on their water content. Our 35 tonnes or so equalled 45cum.

After measuring, Ragnar drove the Scania into the papermill's yard where a giant forklift with enormous jaws lifted the entire load off in just three bites and deposited the logs into a chute. They disappear inside the building, destined to emerge as paper.

David Tarbuck summed up all our thoughts when he concluded at the end of the day: 'in 33 years in the road haulage Industry I have never seen an operation like this or anything working in such appalling weather conditions."

We were all very impressed by Ragnar's stoicism and professionalism — he had not missed a load in 28 years he told us.

The next day the temperature had risen to minus 10 degrees Centigrade and ironically this relative warmth lead to a worsening of weather conditions. With the warmer day came some heavy snow but after a little debate it was decided that we should at least try to keep to the original programme, so we set off in two cars in search of the Arctic Circle.

In blizzard conditions and with a thick layer of snow hiding the road it took two and a half hours to cover the 160km (100 miles) to Jokkmokk, a small Lapland town just inside the Polar region.

The road followed the course of a river that started life up in the mountains on the SwedishNorwegian border and flowed down to the Baltic at Lula. Not surprisingly, there was little other traffic on the move.

Having flown back to Stockholm the last couple of days of Roy Withers' Michelin European Study Award trip included a whistle-stop tour of the Michelin Training Centre, and a lunch-plus-presentation at Svenska Akeriforbundet, the Swedish Road Haulage Associa tion.

Svenska Akeriforbundet is very different from our own RHA. It plays a similar role in that it represents hauliers' interests but also has a more commercial outlook and is involved with the haulage industry at a very practical level.

For instance, a subsididary of SA is SAIFA, which runs 35 commercial vehicle garages throughout Sweden selling fuel, tyres, spares and service for any haulier whether or not he is a member of SA. And SAIFA also owns one of the largest Swedish trailer manufacturers, Kilafors.

The staff of the SA outlined the structure of the Swedish haulage industry, and having seen an example of a "central trucking agency" at work with Ragnar and Lulefrakt we were then told about another type of co-ordination, "transport exchange agencies." These employ small haulage companies or owner-drivers with their vehicles working in the agency's colours, therefore giving the effect of one large fleet.

The agency markets itself as a single company and the agency's traffic staff allocates the work to the hauliers. The agency owns no vehicles itself but does own the depots and looks after the warehousing, administration and marketing. We subsequently visited ti main Stockholm depot of AS the largest of these agenci with 2,700 vehicles working ASG's blue and yellow livery.

is 70 per cent owned by Swedil State Railways, and ASG fr quently chooses to use n transport for long-distan( trunking with lorries operatir the feeder services.

ASG operates 120 depots Sweden and the one we visit€ in Stockholm will soon rank ; one of the largest depots Europe and Scandinavia. The are already two enormous tran shipment and sortation buil, ings on the site with ur derground warhousing, loadir bays down each side and ra way sidings running right ml the heart of each building. third building is due to open in few months' time and I counts 100 loading bays in it.

The sheer size of the operatio was impressive; ASG claims t be one of the top ten freigt movers in Europe and thi system of co-ordinating man small hauliers to work under on banner, combined with the us of rail transport where applic€ ble, seems to work well.

Both Roy Withers and Davi' Tarbuck agreed that the whol week's trip had been quite a experience, and the day span with Ragnar Akerstrom haulint timber out of those silent, froze' forests will be indelibly etchei on our memories.

The incredible hospitaliti shown by our Swedish host: also contributed to a very en joyable and instructive week am Roy Withers returned to Bir mingham with just one worry:" hope this won't make me corn placent when we get some snov back home."