Swedish Three-wheeler is Lively and Economical

Page 69

Page 70

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

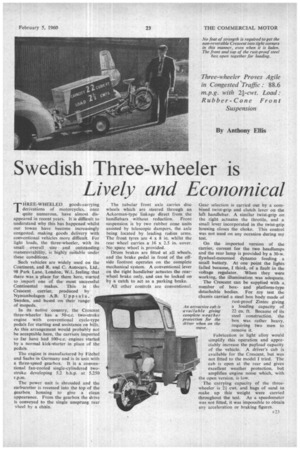

• Three-wheeler Proves Agile in Congested Traffic : 88.6 m.p.g. with 21-cwt. Load: Rubber-Cone Front

Suspension

By Anthony Ellis

HREE-WHEELED goods-carrying derivations of motorcycles, once quite numerous, have almost disappeared in recent years. It is difficult to understand why this has happened whilst our towns have become increasingly congested, making goods delivery with conventional vehicles more difficult. For light loads, the three-wheeler, with its small overall size and outstanding manoeuvrability, is highly suitable under these conditions.

Such vehicles are widely used on the Continent, and R. and C. Autocars, Ltd., 98 Park Lane, London, W,1, feeling that there was ,a place for them here, started to import one of the most successful Continental Makes. This is the Crescent carrier, produced by Nymanbolagen A.B. Upps al a, ' Sweden, and based on their range' of mopeds.

In its native country, the Crescent three-wheeler has a 50-cc. two-stroke engine with conventional cycle-type pedals for starting and assistance on hills. As this arrangement would probably not be acceptable here, the carriers imported so far have had 100-c.c.engines started by a normal kick-starter in place of the pedals.

The engine is manufactured by Fitchel and Sachs in Germany and is in unit with a three-speed gearbox. It is a conventional fan-cooled single-cylindered twostroke developing 5.2 b.h.p. at 5.250 r.p.m.

The power unit is shrouded and the carburetter is recessed into the top of the gearbox housing to give a clean appearance. From the gearbox the drive is conveyed to the single unsprung rear wheel by a chain. The tubular front axle carries disc wheels which are steered through an Ackerman-type linkage direct from the handlebars without reduction. Front suspension is by two rubber cone units assisted by telescopic dampers, the axle being located by leading radius arms. The front tyres are 4 x 8 in. whilst the rear wheel carries a 16 x 2.5 in. cover. No spare wheel is provided.

Drum brakes are fitted at all wheels, and the brake pedal in front of the offside footrest operates on the complete mechanical system. A conventional lever on the right handlebar actuates the rearwheel brake only, and can be locked on by a catch to act as a parking brake.

All other controls are conventional. Gear selection is carried out by a combined twist-grip and clutch lever on the left handlebar. A similar twist-grip on the right actuates the throttle, and a small lever incorporated in the twist-grip housing closes the choke. This control was not used on any occasion during my test.

On the imported version of the carrier, current for the two headlamps and the rear lamp is provided by a 30-w. flywheel-mounted dynamo feeding a small battery. At one point the lights failed because. I think, of a fault in the voltage regulator. When they were working, the illumination was adequate.

The Crescent can be supplied with a number of boxand platform-type detachable bodies. For my test the chassis carried a steel box body made of rust-proof Zintec giving a loading capacity of 22 Cu. ft. Because of its steel construction, the box was rather heavy, requiring two men to remove it.

An attractive cab is available giving complete weather protection for the driver when on the

move.

Fabrication in light alloy would simplify this operation and appreciably increase the payload capacity of the vehicle. A driver's cab is available for the Crescent, but was not fitted to the model I tried. The cab is open at the rear and gives excellent weather protection, but amplifies engine noise which, with the open version, is low.

The carrying capacity of the threewheeler is 24cwt. and bags of sand to make up this weight were carried throughout the test. As a speedometer was not fitted, it was impossible to obtain any acceleration or braking figures. However, in London traffic the Crescent proved quite capable of keeping up with and, indeed, exceeding the general traffic speed because of its good initial acceleration and its narrow width, which allowed it to be taken along the inside or outside of streams of slowmoving vehicles.

I was not so happy with the brakes, which after initial adjustment by taking up the two wiag nuts provided, showed unbalance. It was found later that the footrest fouled the brake Pedal, preventing it from swinging through its fullarc and affecting the distribution of braking.

One of the advantages of a light, lowpowered vehicle should be good fuel economy. However, small two-stroke engines can sometimes show a surprising thirst when driven hard. The Sachs unit in the Crescent does not have this fault. To assess the fuel consumption, I drove the three-wheeler from Waltonon-Thames to the centre of London.

This journey is 21.6 miles, half on open road, with the remainder in dense traffic. The Crescent was driven at full throttle almost continuously, which meant that it was running at its maxi

mum speed of about 30 m.p.h. whenever possible.

The journey was completed in 1 hour 20 minutes, giving an average speed of 16.2 m.p.h. at a fuel-consumption rate of 88.6 m.p.g. Although the average speed may appear low, it is remarkably good when compared with the 1 hour 15 minutes which I regularly take to complete the same trip by car cruising at 50-60 m.p.h. on the out-of-town section. The Crescent made such good time because of its ability to get around slow-moving vehicles.

Impeccable Behaviour

One of the most laudable features of the vehicle was the impeccable behaviour of the engine. It is designed to run on a petrol-to-oil mixture of 25 to 1. As the standard two-stroke mixture supplied by garages in this country is 20 to 1, I used this fuel throughout the test.

The engine was always easy to start. Once firing, it required about a minute to warm up and would then settle down to a really slow tick-over. It was quiet even when accelerating at full throttle and had no perceptible vibration period.

Having arrived at one's destination surprisingly quickly on the Crescent, there are few parking problems. Although it does not have a reverse gear, this. is little handicap. Weight distribution is such that even when the vehicle is fully loaded it is possible to raise the rear wheel by the handle provided and move it like a wheelbarrow.

Steering is rather heavier than I would have expected. . This is probably because of the large-section front tyres and the direct linkage employed. It takes a little time to get used to the direct action, but once one is accustomed to it the steering is pleasantly precise.

As the driver is looking over a flattopped box which does not turn with the steering, it is difficult on first acquaintance to aim the vehicle accurately. However, this effect soon disappears and, in the interim, it is reassuring to note that there is a robust bumper and lifting rail around the box.

The Crescent chassis, with the 100-c.c. engine, costs £145 and the standard steel box body adds £30 to this price. The cab, which is made from Zintec and light • alloy, also costs £30.