Bristol VRT3 Eastern Coach Works double-decker

Page 51

Page 52

Page 54

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

ROAD TEST

and operational trial

by Martin Watkins

LEYLAND has striven to produce two double-decker bus designs—the B15 (CM November 21) and an updated Bristol VRT—in order to satisfy the majority of British operators after the Fleetline and Atlantean are phased out in 1977, This week, following our appraisal of the B15 we are able to report our exclusive road test of a Bristol VRT3 now in service with Hants and Dorset Motor Services.

I found that its encapsulated Leyland 501 engine and G2 gear control have improved a good vehicle marred only by heavy steering.

Particularly creditable were the fuel consumption of 30.841itres / 100km (9.16mpg) obtained on main road running and 46.391itres/100km (6.09 mpg) on simulated bus operation on our Leicester test route.

Like most Bristol chassis this example was bodied by Eastern Coach Works at Lowestoft. The encapsulation of the engine and the ensuing air-ducting arrangements call for a high degree of co-operation between chassis manufacturer and bodybuilder which few

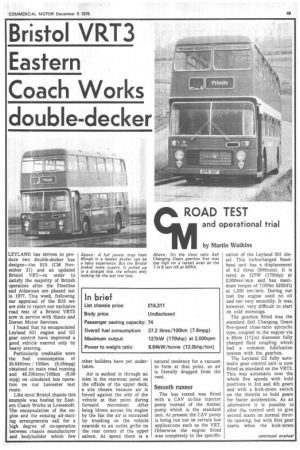

Above : A full power stop from 40mph in a loaded decker can be a hairy experience. But the Bristol brakes were superb. It pulled up in a straight line, the wheels only locking for the last few feet.

other builders have yet undertaken.

Air is sucked in through an inlet in the rearmost panel on the offside of the upper deck, a site chosen because air is forced against the side of the vehicle at that point during forward Movement After being blown across the engine by the fan the air is extracted by trunking on the vehicle nearside to an outlet grille on the rear corner of the upper saloon. At speed there is a

Above : On the close ratio Self Changing Gears gearbox first was too high for a restart even on the 1 in 6 test hill at MIRA.

natural tendency for a vacuum to form at that point, so air is literally dragged from the vent.

Smooth runner

The bus tested was fitted with a CAV in-line injector pump instead of the Ambac pump which is •the standard unit. At present the CAV pump is being run out on certain bus applications such as the VRT. Otherwise the engine fitted was completely to the specific cation of the Leyland 501 diesel. This turbocharged fixedhead unit has a displacement of 8.2 litres (500cuin). It is rated at 127W (170bhp) at 2,000rev/min and has maximum torque of 710Nm 5251bft) at 1,200 rev/min. During our test the engine used no oil and ran very smoothly. It was, however, very difficult to start on cold mornings.

The gearbox fitted was the standard Self Changing Gears five-speed close-ratio epicyclic type, coupled to the engine via a 45cm (171in) diameter fully charged fluid coupling which had a common lubrication system with the gearbox.

The Leyland G2 fully automatic gear control unit is now fitted as standard on the VRT3. This was automatic over the whole five speeds with hold positions in 3rd and 4th gears and with a kick-down switch on the throttle to hold gears for faster acceleration. As an alternative it is possible to alter the control unit to give second starts on normal throttle opening, but with first gear starts when the kick-down position on the accelerator is engaged The bus tested had the optional manual steering fitted in place of power steering included in the Bristol standard specification. This made driving the fully loaded bus very hard work on the tight corners of our new Leicester test route and also made for a poor balance between the energy the driver needed to expend on the different controls. The fully automatic transmission, full air braking and air throttle meant that virtually no effort had to be expended on any of these compared with the steering.

Smooth changes

A senior NBC engineer said the fitment of manual steering prevented drivers from going into corners too quickly, But I think that manual steering offers a greater danger as the driver cannot get lock on quickly enough to get himself out of any awkward situation that may arise. If the vehicle changes gear on tight corners this can result in a slight speed increase, which could put the driver of a manually steered bus into difficulties. National Bus has, perhaps, shown foresight in specifying power steering as standard on future vehicles of this type.

The quality of the gear changes under running conditions controlled by the G2 unit was exceptionally good with no perceptible jerks at all right through the gears from first to fifth. Yet the close ratios I found had one disadvantage, as the bus failed to restart on the 1 in 6 test hill at MIRA. Also changes did not always happen at the moment when I would personally have selected them. It was necessary to stamp very hard on the acceleration pedal to actuate the kick-down mechanism, and not to release any pressure on the pedal while the gear hold was needed.

On similar buses in service with Hants and Dorset I have been told that the kick-down switches are very troublesome and tend to stick in the kickdown position. To my mind it would seem that had the last half inch or so of the accelator travel been designed as the kick-down, both drivers and engineers would be happier. The slight time-delay between releasing the accelerator and the engine decelerating could be annoying in some situations. Several times while I was on town roads cars pulled out in front and caused me to go for the brake quickly, but until I could actually apply the brakes the bus still accelerated.

While driving the bus I did not make much use of the hold positions on the gearbox—and I doubt if many bus drivers on service would. For hill climbs the third or fourth hold positions can be used to prevent the gearbox changing up at its usual actuation speed, and for hill descents holds can be used to give engine braking.

The effectiveness of the Bristol brakes surprised even the Leyland and National Bus engineers present.. Not only did most of the test load of sandbags finish up at the front of the vehicle on the first stop, but also the fuel test tank positioned on the back seat became dislodged and shot forwards. After these had been better secured, test stops at 20, 30 and 40mph were successfully performed.

An examination of the road surface showed that none of the wheels locked up at all during the 20 and 30mph stops. After the 40mph stop black marks showed on the road behind the rear wheels for about the last 2ft travelled before the bus came to rest. Total braking distance for this stop was 105ft 6in and the bus only deviated very slightly from its straight course. A handbrake stop from 20 mph also failed to lock the rear wheels.

The front and rear overhangs of the bus made it imprudent to take it on to the MIRA ride and handling circuit and also called for extreme caution in approaching the test hills. Although the bus would not restart even on the mildest test hill, the 1 in 6, the handbrake held it with no difficulty. On the Leicester test route it restarted without difficulty on a 1 in 10 hill. While at MIRA a fuel consumption test was undertaken on the circuit to support the accuracy of the road-test findings. At MIRA we travelled eight miles stopping for 15 seconds four times per mile and returned a consumption of 6.48 mpg. Predictably, on the hilly Leicester road circuit the consumption dropped to 6.09 mpg.

Timing the bus on the mile straight at MIRA confirmed the accuracy of the speedometer although 10 mph was the lowest speed that would register. This made it impossible to give a precise change point for first to second from the acceleration tests. As the automatic changed gears at different speeds under hard and light acceleration and also when braking, three different gearchange charts are shown on the results page.

It was not possible to reach the top speed of 50mph in the acceleration tests, but 45mph was reached in 71sec.

Double-deckers are usually seen only on town services but en route from Leicester to Oxford via the M1 and A43 the Bristol proved to be very much at home on a longer journey. Top speed was 50mph and rarely fell much below this on the motorway section. Handling was very easy as the bus hardly deviated from the desired course even under crosswinds. The variable ratio manual steering was more at home on main road work as this did not involve the heavy driver effort needed to negotiate tight corners found on urban bus routes.

Smooth braking

Because of the full load of sandbags, the hills on A43 between Towcester and Oxford took their toll. Performance was not sprightly, but it was good enough to return a creditable average speed of 61.95 km/h (38.5mph) overall between Leicester and Oxford. The sharp camber of some of these roads and the soft edges beyond call for caution by the the driver, but the perfect brakes and automatic transmission relieved me of these worries and left me free to concentrate on the road conditions.

I have alwaysbeen a great admirer of the warning lights on Bristol buses and coaches. These are grouped together on a display screen on the dashboard to the drivers left. Instead of the "pinhead" bulbs used by other manufacturers the Bristol warnings are large bulbs under a red glass screen surrounding a central yellow indicator warning light.

The cab layout was very simple and effective as all controls were within easy reach of the driver. The driver's seat itself was very comfortable, but I tended to find myself moving rather forward on the seat and not making use of the high backrest.

The Eastern Coach Works body was particularly impressive. Not a rattle could be heard inside, and the overall noise level inside the bus was extremely low. Even when sitting on the back seat, engine noise only amounted to a Murmur. In my opinion the exterior drive-past noise did not seem to be a vast decrease on previous designs, although Leyland claims a maximum drivepast noise of only 80dBA.

The entrance doors did not let in any draughts; this was perhaps fortunate owing to the limited amount of interior heating. In the lower saloon the heater in the rear, adjoining the engine compartment, worked well, but only a thin stream of lukewarm air from the de misters warmed the front. Passengers upstairs fared better as there were air ducts fitted all along the nearside to emit hot air. In a brief storm on our journey the two-speed wipers worked well, but the screen washers could not be persuaded to start.

As regards routine maintenance, such as checking the oil level, I found no obvious difficulties presented by the encapsulated engine. Unfortunately, to carry out major repairs the side panel and lower bonnet panel have to be removed. To do this 16 bolts threaded into aluminium members have to be taken out. This is, perhaps, vulnerable to heavy-handed fitters.

To sum up : this Bristol would have been a suitable vehicle for all types of operation if power-steering had been fitted. The refusal of Eastern Coach Works to disclose the body price makes costing difficult, but with the chassis priced at £16,311 list I would estimate the complete bus would come at about £24,000 today, although with bulk discount National Bus only paid about £20,000 for it in July.