BUYERS’ GUIDE

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

Page 29

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

THIS WEEK WE BUY...

Full guide available at www.commercialmotor.com

Are 6-to 7-tonne trucks a viable alternative to 7.5-tonners? We examine what you need to look for when buying

In 2000, 7.5-tonne GVW trucks accounted for 28% of all new trucks over 3.5-tonne GVW registered in the UK – a proportion that had dwindled to 12% by 2011. But does this mean we’ve fallen out of love with 7.5-tonners? The removal of grandfather’s rights from car drivers who passed their driving test from 1997 is gradually reducing the number of people able to drive 7.5-tonners without an LGV licence. And these little trucks suffered another body blow a few years ago when speed limiter legislation cut their maximum speed to 90km/h (56mph) and forced them out of the third lane on motorways.

But their real drawback is lack of payload capacity. An 18-tonne GVW boxvan takes a net payload of around 9.7 tonnes, equating to 54% of its gross weight, while a 12-tonner can handle around 6.7 tonnes – 56% of GVW. The average 7.5-tonne boxvan, though, struggles to cope with more than 3 tonnes, just 40% of gross weight, making 7.5-tonners look inherently ineficient. They are the architect of their own downfall. European 7.5-tonners share most key components with 10-tonne and 12-tonne versions, so what comes together as an eficient 12-tonner makes an unduly heavy 7.5-tonner. There is too much truck, not enough payload.

Added burden

It will get worse when Euro-6 emission limits arrive in December 2013. Iveco warns that the additional weight of new emissions reduction kit will add another 200kg to a 7.5-tonner’s kerbweight.

Perversely, the route to more payload might be working at a lower gross weight.

We look here at big vans and light trucks that lie in the twilight zone of 6-tonne to 7-tonne GVW to see if they can provide a more eficient package than the traditional 7.5-tonner.

BIG VANS

The choice of 6 to 7-tonne GVW panel vans was never big but it shrank even further when Renault pulled the plug on its 6.5-tonne Mascott in the UK and Mercedes-Benz axed its 6-tonne Sprinter, leaving just Mercedes’ evergreen Vario and Iveco’s Daily.

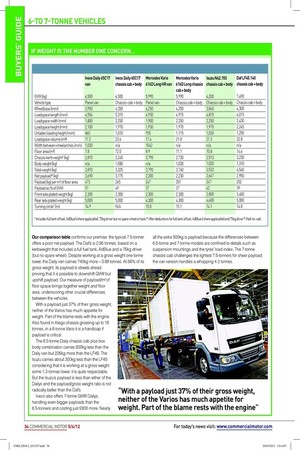

Both Vario and Daily are available either as integral panel vans or chassis cabs (each with a crew cab option). Vario is available at gross weights of 5,990kg and 7,490kg, while Iveco offers Daily models at 6,500kg and 7,000kg. In order to keep the comparisons as close as possible we focus here on the two smaller models, the 6-tonne Vario and the 6.5-tonne Daily, examining panel van and chassis-cab versions of each.

At 6.2-tonne GVW Isuzu’s N62.150 chassis cab is also in the frame, becoming our fifth contender. Last year we would have included the 6.5-tonne Canter from Daimler’s Fuso brand too, but the new 2012 TF Canter range has only 3.5and 7.5-tonne GVW models. A 6.5-tonne Canter is due later this year, but only as a 4x4. Nor is the 6.5-tonne version of Hino’s 300 Series in our line-up. The entire 300 Series range has yet to make the transition from Euro-4 engines to Euro-5 in the UK.

These five lightweights are measured against our representative 7.5-tonner, Daf’s LF45. We are not proclaiming it the lightest or the best, but it would seem perverse to choose anything else as our benchmark. The LF45 has been the UK’s top-selling 7.5-tonner for the past seven years on the trot.

Helpfully, the LF45 is available as a complete truck, bodied at the end of the line in the Leyland Trucks plant. We have chosen the 6.1m (20ft) GRP/ply body with roller-shutter door. This sits nicely on the 4.3m-long wheelbase model, the middle of eight LF45 wheelbase lengths.

We have matched the five contenders as closely as possible to this benchmark. The GRP/ply box bodies for the three chassis cabs are sized to comply with chassis manufacturers’ recommendations and scaled to the size of the vehicles (see table below). Daily, Vario and Isuzu chassis cabs are narrower than the LF45, so we have reduced their body width and height so that these little trucks are not saddled with unduly big boxes.

Iveco Daily 65C17 panel van

The latest Daily became available in the UK early this year. It looks much like any other integral panel van but it is not a monocoque; it has a separate chassis with C-section pressed steel main longitudinals and tubular cross members. At 6.5-tonne GVW there is only one power rating (168hp), one wheelbase (3,950mm) and no choice of roof height. The engine is Iveco’s 3-litre common-rail diesel. Developed by Fiat Powertrain, a variant of this engine is supplied to Fuso for the 7.5-tonne Canter. In the Daily it drives through a six-speed gearbox with overdrive top gear: there is an automated option (Agile) of the same gearbox with electrically powered actuators for gear-shifting and clutch operation.

Iveco Daily 65C17 chassis cab

The same driveline is used in the 6.5-tonne Daily chassis cab, but as well as freedom to choose body specification you also get a choice of four wheelbase lengths – 3,450mm, 3,750mm, 4,350mm and 4,750mm. We used 4,350mm because it is closest to the LF45’s 4,300mm.

Mercedes-Benz Vario 616D Long HR panel van

With a 4,250mm wheelbase, this is the longest of the three 6-tonne Vario panel vans. The others are 3,150mm and 3,700mm. Those are both available in two roof heights, but this long Vario comes only with a high roof. There are three ratings of its 4.3-litre engine: 127hp, 154hp and 175hp. The 616D has the middle of these three, driving through a six-speed gearbox. Like the Daily, Vario has a separate ladder-type steel chassis.

Mercedes-Benz Vario 616D chassis cab

Our chassis cab Vario has the same wheelbase (4,250mm) as the van version, but there are longer (4,800mm) and shorter (3,700mm) variants. There are the same three engine power ratings as the Vario van. The OM904LA engine uses selective catalytic reduction (SCR) and so, like the Daf LF45, needs AdBlue. The Dailys and the Isuzu use exhaust gas recirculation (EGR), thus side-stepping AdBlue.

Isuzu N62.150 chassis cab

With a wheelbase of 3,845mm, the 6.2-tonne Isuzu is the shortest of our contenders. The only option is a stubby 3,395mm, available with a day cab or seven-man crew cab. Other than the LF45, the Isuzu is the only vehicle with a tilt cab, offering good access to its 3-litre, 148hp engine. There is a choice of manual or automated gearboxes, both based on the same six-speed unit with overdrive top gear. The automated (‘Easyshift’) gearbox is a £1,000 option.

Daf LF45.160

Our benchmark 7.5-tonner highlights the choices available when buying what most regard as a ‘proper’ truck. The LF45 comes in eight wheelbases, five power ratings and either day or sleeper cabs. The base rating of the Paccar (née Cummins ISBe) 4.5-litre engine develops 138hp, but other ratings go up to 221hp for a fast and furious 7.5-tonner.

The LF45.160 used here for comparison purposes has 158hp, a typical figure at this weight. The LF45 is the only one in our line-up with a five-speed gearbox as standard. A six-speed manual is a £340 option; plumping for ZF’s automated AS Tronic six-speed transmission adds a hefty £1,750.

Our comparison table confirms our premise: the typical 7.5-tonner offers a poor net payload. The Daf’s is 2.95 tonnes, based on a kerbweight that includes a full fuel tank, AdBlue and a 75kg driver (but no spare wheel). Despite working at a gross weight one tonne lower, the Daily van carries 740kg more – 3.69 tonnes. At 56% of its gross weight, its payload is streets ahead, proving that it is possible to downshift GVW but upshift payload. Our measure of payload/m2 of floor space brings together weight and floor area, underscoring other crucial differences between the vehicles.

With a payload just 37% of their gross weight, neither of the Varios has much appetite for weight. Part of the blame rests with the engine. Also found in Atego chassis grossing up to 16 tonnes, in a 6-tonne Vario it is a handicap if payload is critical.

The 6.5-tonne Daily chassis cab plus box body combination carries 500kg less than the Daily van but 225kg more than the LF45. The Isuzu carries about 300kg less than the LF45: considering that it is working at a gross weight some 1.3 tonnes lower, it is quite respectable. But the Isuzu’s payload is less than either of the Dailys and the payload/gross weight ratio is not radically better than the Daf’s.

Iveco also offers 7-tonne GVW Dailys, handling even bigger payloads than the 6.5-tonners and costing just £800 more. Nearly all the extra 500kg is payload because the differences between 6.5-tonne and 7-tonne models are confined to details such as suspension mountings and the tyres’ load index. The 7-tonne chassis cab challenges the lightest 7.5-tonners for sheer payload; the van version handles a whopping 4.2 tonnes.

ENGINE

The Daily and the Isuzu have 3-litre engines; the Vario and Daf have 4.25 litres and 4.5 litres respectively. The Daily and the Vario have similar power to weight ratios (26hp/ tonne), followed by the Isuzu (24hp/tonne) and the Daf (21hp/tonne).

Differences in swept volumes become more evident in peak torque figures. The Daf has 600Nm, the Mercedes 610Nm. The Daily’s 400Nm and the Isuzu’s 375Nm are no match for that. They partially compensate with impressively wide torque plateaus; fully 1,200rpm for the Daily and the Isuzu, compared with 600rpm for the Daf and just 400rpm for the Vario. When CM tested the 70C17 Daily (18 August 2011) with the same rating (168hp/400Nm) we concluded that the engine was sufficient, even at 7-tonne GVW.

Assuming each vehicle is equipped with the standard default rear-axle ratio and tyres, at 80km/h (50mph) in top gear the Vario’s engine speed will be just 1,708rpm. The Daf’s engine speed will be 1,800rpm. The two 3-litre engines will be turning faster: 2,012rpm in the Daily and 2,083rpm in the Isuzu.

These engine speeds and swept volumes have implications for durability, so one can expect the two larger engines to have the advantage. They are almost certainly designed to achieve a higher B10 life (the point to which 90% of them are expected to run without major overhaul) than the smaller engines. The plethora of elderly Vario-based midibuses plodding around UK streets is testimony to the ruggedness of the Mercedes engine.

As mentioned earlier, while the other vehicles have six-speed boxes as standard, the Daf is the only one with a five-speed gearbox. Choosing the alternative six-speed box actually shortens the top ratio a tad, but provides a deeper first gear for better ‘gradeability’ when starting.

If used on intensive multi-drop work automated gearboxes might well be attractive. ZF supplies automated versions of the six-speed manual gearboxes as options in the Daf and the Daily; Isuzu’s automated option is the six-speed Easyshift box. Vario’s auto option is a fully automatic Allison five-speed gearbox.

These vehicles are on the cusp between trucks and vans. The Daf is pure truck, with 24-volt electrics and a full air-brake system. The Daily comes from the van world, bringing hydraulic brakes and 12-volt electrics. The Vario and the Isuzu are in between. Both have 24-volt electrics; Vario has an air-overhydraulic brake system while the 6.2-tonne Isuzu has hydraulic brakes.

THE CUBE ROUTE

COMPARISONS

If cube not weight is the aim, look no further than the 7.5-tonner. It offers the most length, width and height, producing 32.8m3. That is nearly 40% more than its most capacious rival, the Daily chassis cab and body combination (23.6m3).

Cube in Vario and Isuzu chassis cabs

is limited by body length. Offering just over 17m3, the two panel vans provide no more volume than the biggest 3.5-tonne GVW vans.

Of the two, the Vario has more length and width; the Daily is taller.

It is floor space that really matters for

some operators. This is another win for the 7.5-tonner, but its advantage over the Daily chassis cab is cut to 22% (14.6m2 compared with 12m2). The two panel vans have less floor space and suffer the intrusion of wheel-boxes. The Vario van beats the Daily van (8.9m2 versus 7.8m2).

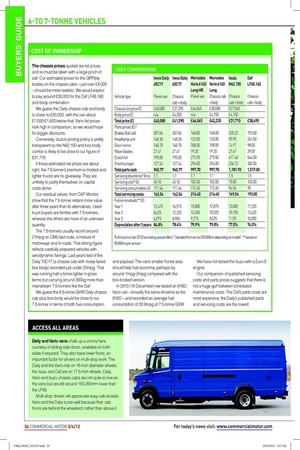

COST OF OWNERSHIP

The chassis prices quoted are list prices, and so must be taken with a large pinch of salt. Our estimated prices for the GRP/ply bodies on the chassis cabs – just over £4,000 – should be more realistic. We would expect to pay around £35,000 for the Daf LF45.160 and body combination.

We guess the Daily chassis cab and body is closer to £30,000, with the van about £1,000-£1,500 below that. Vario list prices look high in comparison, so we would hope for bigger discounts.

Conversely, Isuzu’s pricing policy is pretty transparent so the N62.150 and box body combo is likely to be close to our figure of £31,710.

If those estimated net prices are about right, the 7.5-tonner’s premium is modest and lighter trucks are no giveaway. They are unlikely to justify themselves on capital costs alone.

Our residual values, from CAP Monitor, show that the 7.5-tonner retains more value after three years than its alternatives. Used truck buyers are familiar with 7.5-tonners, whereas the others are more of an unknown quantity.

The 7.5-tonners usually record around 21mpg on CM’s test route, a mixture of motorways and A-roads. That strong figure reflects carefully prepared vehicles with aerodynamic fairings. Last year’s test of the Daily 70C17 (a chassis cab with nicely-faired box body) recorded just under 20mpg. That was running half a tonne lighter in gross terms but carrying around 350kg more than mainstream 7.5-tonners like the Daf.

We guess the 6.5-tonne GVW Daily chassis cab plus box body would be close to our 7.5-tonner in terms of both fuel consumption and payload. The van’s smaller frontal area should help fuel economy, perhaps by around 1mpg-2mpg compared with the box-bodied version.

In 2010 (16 December) we tested an 816D Vario van – broadly the same driveline as the 616D – and recorded an average fuel consumption of 20.9mpg at 7.5-tonne GVW. We have not tested the Isuzu with a Euro-5 engine.

Our comparison of published servicing costs and parts prices suggests that there is not a huge gulf between scheduled maintenance costs. The Daf’s parts costs are most expensive; the Daily’s published parts and servicing costs are the lowest.

ACCESS ALL AREAS

Daily and Vario vans chalk up a victory here, courtesy of sliding side doors, available on both sides if required. They also have lower floors, an important factor for drivers on multi-drop work. The Daily and the Vario ride on 16-inch diameter wheels; the Isuzu and Daf are on 17.5-inch wheels. Daily, Vario and Isuzu chassis cabs are not quite so low as the vans but are still around 150-250mm lower than the LF45.

Multi-drop drivers will appreciate easy cab access. Vario and the Daily score well because their cab floors are behind the wheelarch rather than above it.

AGILITY

These vehicles’ wall-to-wall turning circles throw up a few surprises.

The Daf’s turning circle is the second smallest, beaten only by the nimble Isuzu. The Daily chassis cab looks unwieldy by comparison, a disadvantage for a vehicle that should excel in urban environments.

The Daily van is the narrowest, some 500mm less than the widest (the Daf), handy when squeezing down residential streets constricted by parked cars. The Vario van is around 200mm wider than the Daily. Our body on the Daily, Vario and Isuzu chassis cabs is wider than both the vans but almost 200mm narrower than the Daf’s.

CONCLUSIONS

HORSES FOR COURSES So yes, there are alternatives to the average 7.5-tonner, allowing you to carry heavier payloads at lower gross weight. But would you choose them?

The 6-tonne GVW Vario, both as a panel van and a chassis cab, carries less weight than a 7.5-tonner and its payload-to-gross weight ratio is no better. Nor can it match the volumetric capacity of the 7.5-tonner. A long history plus countless midibuses and coachbuilt UPS parcel vans underlines the robustness of the Vario but at 6 tonnes it fails to challenge a 7.5-tonner.

Isuzu’s 6.2-tonne N62.150 offers a marginally better ratio of payload to gross weight than our 7.5-tonner. However, 1.3 tonnes is too much to give away in terms of gross weight, so the Isuzu can match neither the payload nor volume of a 7.5-tonner. But its payload/m2 of floor space shows that the Isuzu (with an appropriately sized body) should be less prone to overloading than a 7.5-tonner. And not only is it compact, it is also the most agile of our contenders, aiding productivity where space is tight. The Isuzu’s price is keen too.

The two Dailys stand the best chance of persuading operators that there is a valid alternative to the usual 7.5-tonner. The van shines on multi-drop work where streets are narrow. It offers good access for both the driver and his load. Performance is adequate thanks to good power and a wide torque band. It is the antithesis of the 7.5-tonner, providing immense weight capacity but spread across a meagre floor

area and within a relatively small volume. The payload/m2 of floor space is by far the highest, suitable for carrying 1,000mmx1,200mm pallets weighing just over half a tonne each, for example.

The Daily chassis cab is likely to satisfy more operators. Its payload/ volume relationship is better than the van’s. It handles a little more weight than the typical 7.5-tonner, albeit coupled with less deck space and volume. Wider than the van, it is usefully narrower than the 7.5-tonner.

But none of these smaller vehicles is dramatically cheaper than a 7.5-tonner and they have poorer residual values. Their running costs might prove a little lower, but much depends on their durability. Lighter construction and a small engine turning more quickly is not a recipe for longevity. Lighter vehicles need to demonstrate extra productivity over a shorter lifetime. Maybe that is through a combination of carrying a little extra weight, being niftier about town and costing a little less to buy and run.

The low-risk strategy, especially if the duty cycle is arduous or the annual distance is high, is to stay with tried-and-trusted 7.5-tonners. If wary of lighter Japanese models and preferring European chassis, specifying a lighter (but more expensive) body would save 200kg300kg, addressing the payload deficit without reducing robustness. But, to mutilate a metaphor or two, it is horses for courses and there is more than one way to skin the 7.5-tonne cat.