'The hub of excellence'

Page 48

Page 49

Page 50

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

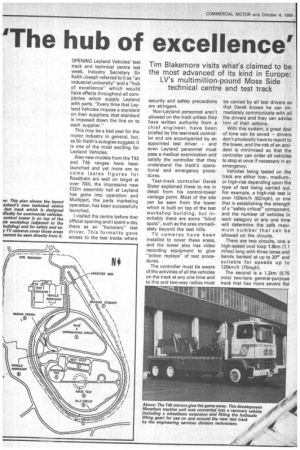

Tim Blakemore visits what's claimed to be the most advanced of its kind in Europe: [V's multimillion-pound Moss Side technical centre and test track

OPENING Leyland Vehicles' test track and technical centre last week, Industry Secretary Sir Keith Joseph referred to it as "an industrial university" and a "hub of excellence" which would have effects throughout all companies which supply Leyland with parts. "Every time that Leyland Vehicles impose a standard on their suppliers, that standard is imposed down the line on to each supplier."

This may be a bad year for the motor industry in general, but, as Sir Keith's eulogies suggest, it is one of the most exciting for Leyland Vehicles.

Also new models from the T43 and T45 ranges have been launched and yet more are to come (sales figures for Roadtrain are well on target at over 700), the impressive new £32m assembly hall at Leyland has gone into operation and Multipart, the parts marketing operation, has been successfully launched.

I visited the centre before that official opening and I spent a day there as an "honorary" test driver. This formality gave access to the test tracks where security and safety precautions are stringent.

Non-Leyland personnel aren't allowed on the track unless they have written authority from a chief engineer, have been briefed by the test-track controller and are accompanied by an appointed test driver — and even Leyland personnel must pass a medical examination and satisfy the controller that they understand the track's operational and emergency procedures.

Test-track controller Derek Slater explained these to me in detail from his control-tower vantage point. Most of the site can be seen from the tower which is built on top of the test workshop building, but inevitably there are some "blind spots", such as the area immediately beyond the test hills.

TV cameras have been installed to cover these areas, and the tower also has video recording equipment to give "action replays" of test procedures.

The controller must be aware of the activities of all the vehicles on the track at any one time and to this end two-way radios must be carried by all test drivers so that Derek knows he can immediately communicate with all the drivers and they can advise him of their actions.

With this system, a great deal of time can be saved — drivers don't physically have to report to the tower, and the risk of an accident is minimised so that the controller can order all vehicles to stop at once if necessary in an emergency.

Vehicles being tested on the track are either low-, medium-, or high-risk depending upon the type of test being carried out. For example, a high-risk test is over 100km/h (62mph), or one that is establishing the strength of a "safety critical" component, and the number of vehicles in each category at any one time will determine the safe maximum number that can be allowed on the circuits.

There are two circuits, one a high-speed oval loop 1.8km (1.1 miles) long with three lanes and bends banked at up to 20° and suitable for speeds up to 120km/h (75mph).

The second is a 1.2km (0.75 mile) two-lane general-purpose track that has more severe flat bends and also serves as an access road to other test-track facilities.

These consist of four test slopes with gradients of 12, 15, 18 and 25 per cent (1 in 8.33, 6.66, 5.55 and 1 in 4); a circular noise test area complying with EEC regulations with approach roads and turnround areas; a steering pad of 100m (328,1ft) diameter with sprinklers that can wet it uniformly; and a pave!corrugation track 0.9km (0.56 miles) long with an adjacent smooth track for accompanying vehicles.

This pave track is particularly interesting for the spacing and height of the cobbles have been carefully chosen. It is generally agreed that pave (or a laboratory simulation of it) is the best way of carrying out endurance tests, but of course the severity of the pave can vary infinitely so that 1,000 miles on one track is not the same as 1,000 miles on another.

Leyland already has a pave circuit at its Spurrier Works and this is more severe than MIRA's, so, in theory at least, any given endurance test should require less time.

But in practice, Leyland has found difficulty in getting consistent results on its old track because the heavy single jolts from the highest cobbles are too severe.

Also if there's an easy way of avoiding the roughest areas, as there is on the Spurrier circuit, then regular test drivers will find it — anyone who's driven a few miles on pave will understand why.

For the new circuit, Leyland's engineers decided that a profile more severe than MIRA's was needed, but less so than the existing one, so the cobble height of each track was measured at 0.5m (1.6ft) intervals and the mean height chosen for the new track. There is no easy way around the new circuit, it has a genuinely random height variation.

When drawing up the specification for the number one and two circuits, height variation was the one thing that the Leyland engineers didn't want. In fact such a fine tolerance was specified for the straights — plus or minus three milli metres over any two points three metres or less apart — that Leyland had difficulty in finding a contractor who was able to comply.

Getting a road surface with a high enough coefficient of friction (0.65p minimum even when wet) and yet also was durable enough was another problem. But that too was overcome and Leyland's vehicle test manager Martin Smith told me that he expected a life of twenty years from the circuits before there was any degradation.

In spite of its high specification — the test track is by no means the most expensive part of Leyland's £22m investment at Longmeanygate — its final cost was just £5m.

It is the sophisticated test equipment inside the buildings that really begins to bite into the capital expenditure budget, but that can easily be justified by the amount of development time it can save.

The electro-hydraulic test equipment, for example, particuarly when used in conjunction Nith the pave circuit, can 3reatly accelerate endurance .esting and by using computer late logging, previous results ire always readily to hand.

Fully laden maximum-weight tehicles will be tested on the :lectro-hydraulic ride simulator, Ind no ordinary building could vithstand the forces involved. rhe answer to this problem has esulted in a very impressive ;tructure.

The ride simulator area is isoated from the building by nounting its base (which is a 7m x 9m x 5.7m reinforced oncrete block weighing approxmately 1,500 tonnes) on high lerformance air springs. This gust be the ultimate in air susension, but it doesn't come heaply.

The semi-anechoic chamber 'so has to be isolated from the uilding, in this case to reduce ackground noise, but this tructure weighs a mere 1,200 )ns and steel springs are used ) suspend it.

Just listing some of the other quipment to be found in the )st buildings gives some idea of le technical centre's testing 3pabilities. There is a £400,000 rake test rig which will be used ) study the performance and urability of braking systems uner dynamic conditions; a Doling system test rig; an envi)nmental chamber for compoents and systems; a fan and idiator test rig; and a computer system that can correlate data from all the rigs and present it in a way suitable for compiling a final report.

It is of course true that Leyland has had (or had access to) many of these facilities before but never all together in one place.

As Leyland's chief engineer, test operations Dr Herman Bruns put it: "This is a major advance because it is important to have the same people following a vehicle through all its development tests. Development time can be reduced this way, and to do this is one of our objectives."

He went on to explain that the technical centre as it now stands is only one phase of the development. In 1978 the decision was taken that the originally budgeted figure of £33m for the new centre would have to be reduced to £22m so phase two was postponed.

Included in the phase two de‘,elopment was a larger office block, a full climatic chamber that could house complete vehicles and gearbox and axle testing rigs.

Some facilities, such as a ride and handling circuit or horizontal straights, were not included on the test track simply because they wouldn't be cost-effective — it makes more sense for Leyland to use existing facilities — and as for a full-size aerodynamic wind tunnel, that would cost somewhere near f10m on its own.

As far as test equipment is concerned, vehicle manufacturers generally are less secretive than most people realise. At the planning stage Leyland's technical centre design team, under Bill Stephenson, visited all the major European vehicle manufacturers' sites and were welcomed at each.

Leyland has a similarly open attitude, and while strict security will always be maintained at Longmeanygate the company will be quite happy to allow other vehicle and component manufacturers to use the facilities, at a commercial rate of course, and obviously Leyland's own products will always take priority.