LIALAND I N THF

Page 58

Page 59

Page 60

Page 61

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By John F. Moon,

A.M.I.R.T.E.

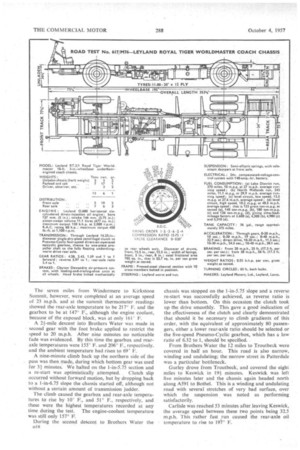

IHAVE just completed a 513-mile endurance test of a Leyland Royal Tiger Worldmaster on an exacting route extending to Annan in the north and Lichfield in the south. It is one of the heaviest passenger vehicles ever to be taken through the Lake District, but a course from Windermere to Troutbeck, over the narrow winding road which includes the Kirkstone Pass, was completed at an average running speed of 23 m.p.h. This speaks well for the engine power and the steering and braking safety.

The journey over the Kirkstone Pass was merely part of a 270-mile circuit made from the Leyland works, passing northwards through the Lake District, turning at Annan—eight miles over the Scottish border—and returning along the main road over Shap Fells. This run was completed at an average speed of 27 m.p.h., and although the chassis was driven hard on many occasions, the overall fuel consumption rate was 10 m.p.g.

Immediately this trip had been completed, the chassis was taken as far south as Lichfield, part of the course including the northern Peak District. Despite bad weather during the latter part of the run, the 243-mile course was covered at an average running speed of 29 m.p.h., the fuel-consumption rate being 11.1 m.p.g.

The chassis supplied for test was an RT.3/1 model, a 16-ft. 3-in.-wheelbase design suitable for 30-ft. by 8-ft. bodywork. The standard specification includes the Leyland 0.680 150-b.hp, D16 horizontal oil engine, Pneumo-Cyclic direct-air-operated gearbox, 9-in, wormdrive axle and air brakes.

Although a fluid coupling has until recently been a standard component in the transmission line, in August, the Leyland 161-in.-diameter centrifugal clutch was offered as a production option, and this unit was fitted to the test chassis. During the test the clutch was found to give a remarkably smooth take-off of power under most conditions, whilst it offers undoubted advantages in respect of fuel economy, in that the transmission losses normally associated with a hydraulic coupling are abolished.

A 5.4 to 1-ratio rear axle was fitted, this being eminently suited to highspeed running in hilly country. A ratio of 4.8 to 1 is offered for operation over more level routes where speeds of up to 60 m.p.h. are desirable, whilst a 6.25 to 1 axle can be fitted for stage-carriage operation.

Complete with fuel, water, lubricants and batteries, the RT.3/1 chassis weighs 5 tons 51 cwt., and it was loaded to a gross weight of 13 tons 2+ cwt. (less driver and observer). Some of this weight was accounted for by a temporary cab. Assuming a body weight. of about 2+ tons, the equivalent of 80 passengers was being carried.

The drivers for the test, in addition to myself, were John Thorn, of The Commercial Motor, and Mr. A. Gurley and Mr. R. McIntosh, of the Leyland Motors experimental department. Only two people were on the chassis at any lime, the remainder travelling in the

photographer's car, which covered the northern section of the test.

When we left the Leyland ' works with McIntosh

driving, the weather was dry but cloudy and the ambient temperature was 570 F. All the running units were cold. As we entered Preston, 15 minutes and six milel later, the temperature of the water in the cylinder block had risen to 145° F., at which it remained for several hours.

Considering the tortuous route through Preston and the amount of traffic encountered, we did well to clear the northern limits within eight minutes, but it was possible to use top gear through most of the town.

Having passed some impressive signs of the new Preston by-pass, good time was made along the first half of the Lancaster road, which was surprisingly clear of traffic, and at times the speed rose to 45 m.p.h. (the governed speed of the engine). Towards Galgate a certain amount of heavy traffic was encountered which reduced the speed to 30 m.p.h., but Lancaster was entered 54 minutes after leaving the works and the average speed for the first hour's running was 29 m.p.h.

At this stage the gearbox and rear axle had still not reached a comfortable working temperature. Heavy traffic was encountered north of Lancaster, but after Carnforth it thinned out a little and, apart from spas modic holiday traffic and one large flock of sheep, we virtually had the road to ourselves. Two hours after leaving the works we entered Kendal-49 miles [corn Leyland.

Here the first change of drivers was made and I took the wheel. The A591 road from Kendal to Windermere, although neither wide nor straight, caused no long _delays, At Windermere a sharp right turn brought us on to the A592 road which leads to the Kirkstone Pass, and after about four miles of undulating and extremely narrow road the 1-in-12 climb to the top of the pass was started. Much of this ascent was made in second gear, but on gradients steeper than 1 in 8, first gear had to be employed. The seven miles from Windermere to Kirkstone Summit, however, were completed at an average speed of 23 m.p.h. and at the summit thermometer readings showed the rear-axle temperature to be 217° F. and the gearbox to be at 147° F., although the engine coolant, because of the exposed block, was at only 161° F. A 24-mile descent into Brothers Water was made in second gear with the foot brake applied to restrict the speed to 20 m.p.h. After nine minutes no noticeable fade was evidenced. By this time the gearbox and rearaxle temperatures were 155° F. and 206° F., respectively. and the ambient temperature had risen to 69' F.

A nine-minute climb back up the northern side of the pass was then made, during which bottom gear was used for 31 minutes. We halted on the 1-in-5.75 section and a re-start was .optimistically attempted. . Clutch slip occurred without forward motion, but by dropping back to a 1-in-6.75 slope the chassis started off, although not without a certain amount of transmission judder. The climb caused the gearbox and rear-axle temperatures to rise by 10' F., and 51° F., respectively, and these were the highest temperatures recorded at any time during the test. The engine-coolant temperature was still only 157° F.

During the second descent to Brothers Water the

D1 8

chassis was stopped on the 1-in-5.75 slope and a reverse re-start was successfully achieved, asreverse ratio is lower than bottom. On this occasion the clutch took up the drive smoothly. This gave a good indication of the effectiveness of the clutch and clearly demonstrated that should it be necessary to climb gradients of this order, with the equivalent of approximately 80 passengers, either a lower rear-axle ratio should be selected or the five-speed Pneumo-Cyclic gearbox, which has a low ratio of 6.32 to 1, should be specified. .

From Brothers Water the 12 miles to Troutbeck were covered in half an hour. This road is also narrow, winding and undulating; the narrow street in Patterdale was a particular bottleneck.

Gurley drove from Troutbeck, and covered the eight miles to Keswick in 19i minutes. Keswick was left five minutes later and the chassis again headed north along A591 to Bothel. This is a winding and undulating road with several stretches of very bad surface, over which the suspension was noted as performing satisfactorily. Carlisle was reached 53 minutes after leaving Keswick, the average speed between these two points being 32.5 m.p.h. This rather fast run caused the rear-axle oil temperature to rise to 10° F.

Having passed through Carlisle in 10 minutes, the Scottish border was crossed six miles and 10 minutes later, and the long straight stretches on the road through to Annan permitted a high cruising speed to be maintained. Annan itself, eight miles from Gretna Green, was reached 15 minutes after crossing the border.

At Annan a delay of Efhours was caused while temporary repairs were made to the photographer's car, which seemed to be suffering through having to keep ahead of the Leyland, but it was still fine and sunny when eventually we left, with Thorn driving. The road to Canonbie is not particularly wide, but the 15 miles from Annan were covered in 28 minutes.

From Canonbie, the chassis was taken along the A6 road to Carlisle, where it was possible to maintain maximum speed for long stretches and cover 15 miles in 24 minutes. There were few delays in Carlisle, which was negotiated in 11 minutes, and the Carlisle-Penrith stretch was covered at an average speed of 39 m.p.h.

Shap Crossed at Speed

Thorn maintained an average speed of 30 m.p.h. between Penrith and Kendal, including crossing Shap. During the ascent of the northern slope of Shap, which lasted nearly 31 minutes, more than half the time was spent in top gear.

At Kendal, McIntosh took over the driving again and between Kendal and Preston-43 miles—he kept up an average speed of 29 m.p.h. By. the time the works were reached, 18 minutes later, we had covered a distance of 270 miles and the total running time was 10 hours.

After a half-hour break the chassis was taken over by two other Leyland experimental drivers, who had 81 hours to put in as many miles as they possibly could, taking in part Of the Peak District and aiming to get as far south as Lichfield. Neither Thorn nor myself accompanied them on this run, but their time and mileage log showed that little time was lost, despite the hilly nature of the first part of the route and the heavily built-up sections between Lichfield and Leyland on the way back.

Having stopped for only 10 minutes during the night and having driven for over 31 hours in continuous rain, these two drivers brought the chassis in with 243 miles more on the mileometer, as a result of which 22 gal. of fuel were needed to replenish the tank.

This circuit, although not so hilly as the course taken the preceding day, is a difficult one on which to keep up a high average speed. The fuel-consumption rate of 11.1 m.p.g. indicate§ that the WorIdmaster can be surprisingly economical when driven hard over reasonably level roads.

Both Thorn and myself were more than pleased with the way that the chassis handled. The high power-to

weight ratio made for fast acceleration, even in top gear, as the short-distance tests made later were to prove.

The brakes were extremely powerful and not once was it necessary to use the emergency pressure which cuts in at 60 lb. pedal pressure. Indeed, as the brake-line pressure gauge showed, normal retardation was at 10 p.s.i.

The Pneumo-Cyclic gearbox worked faultlessly and when accelerating at full throttle the gears engaged smoothly because of the controlled rate of gear brakeband application. The gear lever in the Leyland layout is mounted on a pedestal to the left of the driver and, being large (although the travel is short), is easy to handle. In my opinion, this arrangement is preferable to a smaller lever mounted on a steering column.

Hill-Holder Useful

As the gearbox included the Hill-Holder device, it was unnecessary to apply the brakes when stopped facing up a gradient with a forward gear engaged, or facing down a gradient with the reverse gear engaged. The effectiveness of this device was proved on several occasions when making tests on gradients.

It was difficult to sum up the suspension completely because the cab, being well ahead of the front axle, was not advantageously placed in this respect. However, over most surfaces the suspension seemed satisfactory, although a little hard, and the absence of roll when cornering was noteworthy. The steering ratio was low, requiring 7+ turns of the wheel from lock to lock, but the 22-in.-diameter wheel was easy to handle.

Short-distance tests were made in the Leyland area, extremely satisfactory acceleration and braking figures being obtained. When braking from 30 m.p.h., using full pedal pressure, both rear wheels locked on each. occasion. Little lag was evidenced in the system, as shown by the slight difference between the maximum Tapley meter readings and the average stopping distances. The brake-line pressure during this test was 85 p.s.i. When applied from 20 m.p.h. the hand brake gave an efficiency reading of 20 per cent.

Two fuel-consumption tests were made over a 5.9-mile level circuit, using a calibrated test tank. The first of these was conducted without exceeding 30 m.p.h. and produced 13.5 m.p.g., whilst the second was made at continuous full throttle, 10.2 m.p.g. being obtained.

No maintenance tasks were carried out on the chassis; without a body these would have proved nothing. The chassis has, however, been designed to reduce maintenance time. The use of Bendix-Westinghouse worm-drive slack-adjusters on the brakes, the incorporation of a centrifugal engine-oil cleaner and the elimination of auxiliary belt drives assist in this direction.