Continental rift

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

you might not guess from the gentle West Country tones, but John Golding is angry. Beneath the mild mannered exterior, indignation burns slowly but as intense as the outrage of any short-fused French farmer, fisherman or trucker. And it

is French, and Dutch, hauliers aided and abetted by the pin-striped men at HM Treasury—that have got the goat of this 60year-old heavy haulier from Gloucester.

Al] UK hauliers complain that they carry more than their fair share of taxation which, gallingly, is not re-invested in the road system. But the taxation burden for heavy haulage specialists is not just heavy, it is irrational, unfair and—John Golding fears — unbearable.

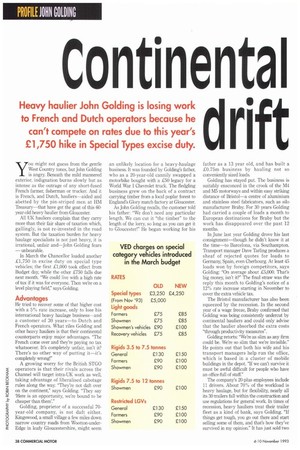

In March the Chancellor loaded another 1:1,750 in excise duty on special type vehicles; the first £1,000 took effect from Budget day, while the other £750 falls due next month. "We could live with a high rate of tax if it was for everyone. Then we're on a level playing field," says Golding.

Advantages

He tried to recover some of that higher cost with a 5% rate increase, only to lose his international heavy haulage business—and a customer of 30 years—to Dutch and French operators. What riles Golding and other heavy hauliers is that their continental counterparts enjoy major advantages. "The French come over and they're paying no tax whatsoever. It's completely unfair, isn't it? There's no other way of putting it—it's completely wrong!"

A growing worry for the British STGO operators is that their rivals across the Channel will target intra-UK work as well, taking advantage of liberalised cabotage rules along the way. "They're not daft over on the continent," says Golding. "They say 'Here is an opportunity, we're bound to be cheaper than them'."

Golding, proprietor of a successful 70year-old company, is not daft either. Kingswood, a small village a few miles down narrow country roads from Wootton-underEdge in leafy Gloucestershire, might seem an unlikely location for a heavy-haulage business. It was founded by Golding's father, who as a 20-year-old cannily swapped a motorbike bought with a £50 legacy for a World War I Chevrolet truck. The fledgling business grew on the back of a contract carrying timber from a local poplar forest to England's Glory match factory at Gloucester.

As John Golding recalls, the customer told his father: "We don't need any particular length. We can cut it "the timber" to the length of the lorry, so long as you can get it to Gloucester!" He began working for his father as a 13 year old, and has built a £0.75m business by hauling not so conveniently sized loads.

Golding has stayed put. The business is suitably ensconced in the crook of the M4 and M5 motorways and within easy striking distance of Bristol—a centre of aluminium and stainless steel fabricators, such as silo manufacturer Braby. For 30 years Golding had carried a couple of loads a month to European destinations for Braby but the work has disappeared over the past 12 months.

In June last year Golding drove his last consignment—though he didn't know it at the time—to Barcelona, via Southampton. Transport manager Dave Tarling produces a sheaf of rejected quotes for loads to Germany, Spain, even Cherbourg. At least 45 loads won by foreign competitors, says Golding: "On average about £5,000. That's big money, isn't it?" The final straw was the reply this month to Golding's notice of a 12% rate increase starting in November to cover the extra vehicle tax.

The Bristol manufacturer has also been squeezed by the recession. In the second year of a wage freeze, Braby confirmed that Golding was being consistently undercut by continental hauliers and could only advise that the haulier absorbed the extra costs "through productivity measures".

Golding retorts: "We're as slim as any firm could be. We're so slim that we're invisible." He points out that both his wife and his transport managers help run the office, which is based in a cluster of mobile buildings in the depot. "If we can't survive it must be awful difficult for people who have an office-full of staff."

The company's 20-plus employees include 11 drivers. About 70% of the workload is heavy haulage, but for flexibility, nearly all its 30 trailers fall within the construction and use regulations for general work. In times of recession, heavy hauliers treat their trailer fleet as a kind of bank, says Golding. "If things get tough, you go out there and start selling some of them, and that's how they've survived in my opinion." It has just sold two under-used Crane Fruehauf 60-tormers to Trinidad.

That eases cash flow, which is sorely strained by the increase in vehicle tax on special types to 15,000. But it's not just the amount, but the lack of rationale and the inflexibility of the licensing regime that is trying Golding's patience. He assumes the criteria for Special Types tax are based on a vehicle width of 14ft 3iri, length 60ft and weight 38t. "I might be wrong. I've yet to find someone who can tell me."

Escaped

Ik admits that Special Types escaped lightly formerly—with a .£150 charge when the tax was introduced for vehicles that were too wide or heavy to go to the test station and comply with construction and use regulations. Golding paid the higher rate on his vehicles which have always been tested and plated. With no apparent sense of irony, he points out that the police did not pull in the heavy haulier's abnormal loads and insist a rebate was claimed.

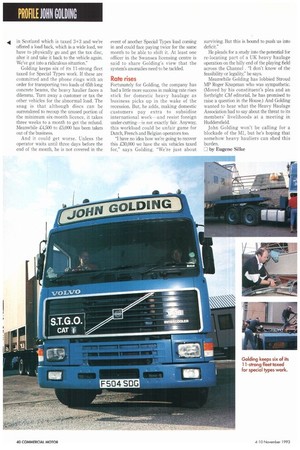

But now, he points out: "If we have a lorry in Scotland which is taxed 3+3 and we're offered a load back, which is a wide load, we have to physically go and get the tax disc, alter it and take it back to the vehicle again. We've got into a ridiculous situation," Golding keeps six of its 11-strong fleet taxed for Special Types work. If these are committed and the phone rings with an order for transporting two loads of 65ft-long concrete beams, the heavy haulier faces a dilemma. Turn away a customer or tax the other vehicles for the abnormal load. The snag is that although discs can be surrendered to recoup the unused portion of the minimum six-month licence, it takes three weeks to a month to get the refund. Meanwhile £4,500 to £5,000 has been taken out of the business.

And it could get worse. Unless the operator waits until three days before the end of the month, he is not covered in the event of another Special Types load coming in and could face paying twice for the same month to be able to shift it. At least one officer in the Swansea licensing centre is said to share Golding's view that the system's anomalies need to be tackled.

Rate rises Fortunately for Golding, the company has had a little more success in making rate rises stick for domestic heavy haulage as business picks up in the wake of the recession. But, he adds, making domestic customers pay extra to subsidise international work—and resist foreign under-cutting—is not exactly fair. Anyway, this workload could be unfair game for Dutch, French and Belgian operators too.

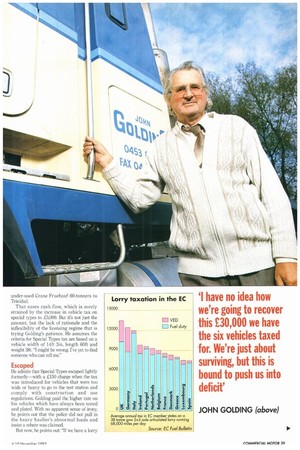

"1 have no idea how we're going to recover this £30,000 we have the six vehicles taxed for," says Golding. "We're just about surviving. But this is bound to push us into deficit."

He pleads for a study into the potential for re-locating part of a UK heavy haulage operation on the hilly end of the playing field across the Channel . "I don't know of the feasibility or legality," he says.

Meanwhile Golding has lobbied Stroud MP Roger l'napman who was sympathetic. (Moved by his constituent's plea and an forthright CM editorial, he has promised to raise a question in the House.) And Golding wanted to hear what the Heavy Haulage Association had to say about the threat to its members' livelihoods at a meeting in Huddersfield.

John Golding won't be calling for a blockade of the MI, but he's hoping that somehow heavy hauliers can shed this burden.

CI by Eugene SiIke