BRISTOL RE SINGLE-DECK BUS CHASSIS

Page 64

Page 65

Page 66

Page 71

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By A. J. P. WILDING, AM I Mech E, MIRTE

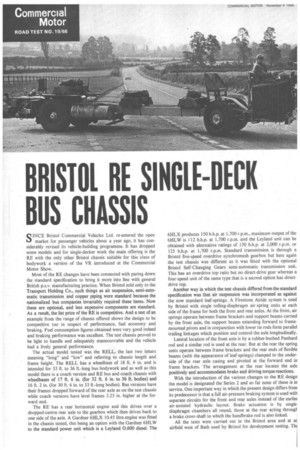

SINCE Bristol Commercial Vehicles Ltd. re-entered the open 1.,7 market for passenger vehicles about a year ago, it has considerably revised its vehicle-building programme. It has dropped some models and for single-decker work the main offering is the RE with the only other Bristol chassis suitable for this class of bodywork a version of the VR introduced at the Commercial Motor Show.

Most of the RE changes have been connected with paring down the standard specification to bring it more into line with general British p.s.v. manufacturing practice. When Bristol sold only to the Transport Holding Co., such things as air suspension, semi-automatic transmission and copper piping were standard because the nationalized bus companies invariably required these items. Now these are optional, and less expensive components are standard. As a result, the list price of the RE is competitive. And a test of an example from the range of chassis offered shows the design to be competitive too in respect of performance, fuel economy and braking. Fuel consumption figures obtained were very good indeed and braking performance was excellent. The test chassis proved to be light to handle and adequately maneouvrable and the vehicle had a lively general performance.

The actual model tested was the RELL, the last two letters meaning "long" and "low" and referring to chassis length and frame height. The RELL has a wheelbase of 18 ft. 6 in. and is intended for 33 ft. to 36 ft.-long bus bodywork and as well as this model there is a coach version and RE bus and coach chassis with wheelbases of 17 ft. 6 in. (for 32 ft. 6 in. to 36 ft. bodies) and 16 ft. 2 in. (for 30 ft. 6 in. to 33 ft.-long bodies). Bus versions have their frames droppedlorward of the rear axle as on the test chassis while coach versions have level frames 3.25 in. higher at the forward end.

The RE has a rear horizontal engine and this drives over a dropped-centre rear axle to the gearbox which then drives back to one side of the axle. A Gardner 6HLX 10.45 litre engine was fitted in the chassis tested, this being an option with the Gardner 6HLW to the standard power unit which is a Leyland 0.600 diesel. The 6HLX produces 150 b.h.p. at 1,700 r.p.m., maximum output of the 6HLW is 112 b.h.p. at 1,700 r.p.m. and the Leyland unit can be obtained with alternative ratings of 130 b.h.p. at 2,000 r.p.m. or 125 b.h.p. at 1,700 r.p.m. Standard transmission is through a Bristol five-speed overdrive synchromesh gearbox but here again the test chassis was different as it was fitted with the optional Bristol Self-Changing Gears semi-automatic transmission unit. This has an overdrive top ratio but no direct-drive gear whereas a four-speed unit of the same type that is a second option has directdrive top.

Another way in which the test chassis differed from the standard specification was that air suspension was incorporated as against the now standard leaf-springs. A Firestone Airide system is used by Bristol with single rolling-diaphragm air-spring units at each side of the frame for both the front and rear axles. At the front, air springs operate between frame brackets and support beams carried by the front axle, the support beams extending forward to framemounted pivots and in conjunction with lower tie rods form parallel trailing linkages which position and control the axle longitudinally.

Lateral location of the front axle is by a rubber-bushed Panhard rod and a similar rod is used at the rear. But at the rear the spring units operate between frame brackets and the rear ends of flexible beams (with the appearance of leaf-springs) clamped to the underside of the rear axle casing and pivoted at the forward end in frame brackets. The arrangement at the rear locates the axle positively and accommodates brake and driving torque reactions.

With the introduction of the various changes to the RE design the model is designated the Series 2 and so far none of these is in service. One important way in which the present design differs from its predecessor is that a full air-pressure braking system is used with separate circuits for the front and rear axles instead of the earlier' air-assisted hydraulic layout. Brake actuation is by singlediaphragm chambers all round, those at the rear acting througt a brake cross-shaft to which the handbrake rod is also linked.

All the tests were carried out in the Bristol area and at airfield west of Bath used by Bristol for development testing. Th

weather at the time of most of the tests was dry but it was cold with the maximum temperature at any time,13 deg. C (55 deg. F). Fuel consumption tests were carried out first to give the stretch planned for brake tests time to dry out after early morning rain. The perimeter track of the airfield was used for these, two laps of the 3-mile circuit being made. Against the usual belief, the perimeter circuit of this particular airfield was far from being flat, having some slight undulations for most of the way and one fairly long (300 yards) gradient. I would say that as far as fuel consumption testing was concerned the circuit was comparable to others frequently used for COMMERCIAL MOTOR tests. Unfortunately, the RE was not loaded to its maximum designed weight. The gross figure of 10 ton 6 cwt. was 17 cwt. short of this which must be taken into account when considering the consumption figures obtained. Another point which must be taken into account is the fact that the RE was tested in chassis form; with a body there would have been increased wind resistance which would have reduced the figures obtained. But wind resistance would only have been a factor in the steady-speed runs with less effect on the twostops per mile consumptions and virtually none on the six stops per mile tests. It is difficult to assess the consumption that an operator would obtain with an RE on stage-carriage work because conditions, loading, terrain and so on vary so widely but I think it would be safe to assume that with the layout as on the test chassis between 11 and 13 m.p.g. should be obtained.

Acceleration tests followed the fully-laden consumption tests on the first day and the RE put up a good performance on these. The fitting of semi-automatic transmission helped in producing good times for the through-the-gears runs---they were as good as figures obtained with p.s.v. running at higher power-to-weight ratios tested previously. On the runs from 10 m.p.h. the top, overdrive, ratio in the gearbox was used because this unit did not have a direct drive and fourth ratio gave a maximum speed of only 39 m.p.h. These runs are comparable with direct-drive runs in chassis having a rear axle ratio of 3.35 to 1 and therefore the times obtained were commendable. The engine pulled without hiss from

speeds as low as 8 m.p.h. in top gear.

When the tarmac on the airfield had dried out brake tests were completed and very good figures as recorded in the results table were obtained. The stopping distances were shorter than on p.s.v. chassis of the same type tested recently and represent actual efficiencies—from the point that the pedal was first pressed to a point at which the vehicle stopped—of around 60 per cent. These compare with Tapley meter readings for maximum deceleration of 70 per cent from 20 m.p.h. and 67 per cent from 30 m.p.h. that were recorded on the stops and show that there was little delay in the system. The Tapley meter reading obtained for handbrake tests was 37 per cent which is very high indeed and this in spite of the fact that the handbrake could have done with some adjustment as the lever was right back and a bit awkwardly placed for the application of full effort when in the "on" position.

Having less load on the chassis than it is designed to carry would have helped in giving improved figures but against this must be set the fact that the chassis had only done 72 miles on the road so that the brakes could not have been fully bedded in. The test vehicle was the Show exhibit by Bristol at Earls Court last month so it had covered much more distance—but on the back of a semitrailer. A notable aspect of the brake tests was that there was no locking of the wheels to speak of. On only one stop was there a mark on the road and this was from one of the front wheels which could have been due to a patch on the surface of the road with low adhesion. Even when getting the high handbrake retardations there was no marking by the rear tyres.

We had a lot of difficulty in finding a suitable hill for gradientperformance tests in the area around Bath and Bristol and eventually settled for one a little way to the north of Wells, Somerset. Exact details of the average gradient could not be obtained but I would estimate it to be about 1 in 12. The length was 0.8 miles and the maximum gradient 1 in 8, this being the figure for at least half the hill. Although not as steep as those normally used on CM tests, the results are reasonably comparable. Total time for a maximum-power ascent was 2 min. 56 sec. and on the climb second gear was the lowest used—for 1 min. 41 sec.—and the minimum road speed was 14 m.p.h. Brake fade characteristics were assessed on the hill by making a run down in neutral with the brakes applied to keep the speed to 20 m.p.h. After a run lasting 2 min. 12 sec. a maximum pressure brake stop at the bottom produced a Tapley meter reading of 57 per cent which showed that there had not been enough fade to worry about.

A steeper hill was required for stop-and-start and handbrake holding tests and this was eventually found close to Bristol. The gradient was 1 in 6 and the RE handbrake held the chassis easily both facing up and down the slope. Easy restarts in these positions were made in first and reverse. The steeper hill, although somewhat severe by our normal standards, would have been satisfactory for the hill-climb and fade tests but by the time it was found the rush hour was on in Bristol and the high volume of traffic on the hill made repeat tests impracticable. However, in climbing to the steepest section and then to the top to turn round, the RE showed a more than adequate performance.

The final figures obtained on the test were the maximum speeds in the gears which were 9.5, 15, 25.5, 39 and 58 m.p.h.

As the figures obtained on the test show, the Bristol RE gives a good general performance on the road. I found no point on which the design could be criticized. Steering was light, braking progressive and positive and performance as lively as can be expected on a vehicle of this type. As the test was carried out on a chassis, things such as engine-noise level could not be assessed. The suspension gave a satisfactory ride both fully and partly laden although in both conditions there was a little more "bumpiness" than I would have expected-but not enough for passengers to notice.

In general construction the RE is typical of British high-quality p.s.v. design. Components are robustly made and the chassis should give the long life expected by British operators of this class of machine. There were a number of interesting points about the test chassis which have not been mentioned and which are options. One of these was an exhaust water heater for saloon heating which is fitted in a branch in the exhaust system. Engine-cooling water passes through the unit on its way to the radiator and engine-jacket water heating is augmented. This heat can then be ducted from the radiator to the body saloon. The exhaust gases which are diverted through the heater go through a thermostatically controlled valve with overriding manual control.

It is interesting that Bristol do not fit a fan on the RE and on the test vehicle a Varivane radiator shutter was fitted. This is thermostatically operated by a Bristol-designed mechanism and can be fitted with or without the exhaust water heater but when used with this unit it assists in maintaining optimum engine operating temperature.

List price of the RELL in standard form (with Leyland 0.600 engine and so on) is £3,335. Options on the test chassis were the Gardner 6LX which adds £385, fluid clutch and five-speed semiautomatic transmission £364, air suspension £206, exhaust water heater and Varivane shutter £135 15s., and Clayton Dewandre automatic lubrication £87, bringing the total price as tested to £4,512 15s.