Vehicle costing in management

Page 67

Page 68

Page 69

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

IN the last five articles I have examined the various ways in which technology can help us to run our fleet. These include electronic devices to monitor many aspects of vehicle performance and computers to speed up the analysis of data. We are now able to measure fuel consumption more accurately, establish the precise cost of maintenance, and generally improve the efficiency of our fleet.

Reliable information can also be used to determine vehicle replacement policy and to specify the type of vehicle most suited to a particular operation. These elements of the business are important in their own right and are closely related to the subject of this article, vehicle costing. We need to collect information on fuel consumption and maintenance in order to measure the costs of our fleet, and these costs are used to establish the kind of vehicle we require and when we need to replace it.

Accurate vehicle costing is an essential part of transport management, and it can now be done in a variety of ways. Many of these have arisen from the new technology which can be used to collect and analyse the data.

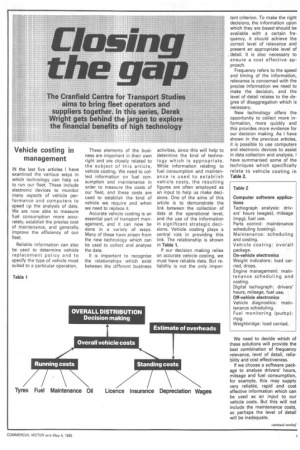

It is important to recognise the relationships which exist between the different business

activities, since this will help to determine the kind of technology which is appropriate. While information relating to fuel consumption and maintenance is used to establish vehicle costs, the resulting figures are often employed as an input to help us make decisions. One of the aims of this article is to demonstrate the link between the collection of data at the operational level, and the use of the information in significant strategic decisions. Vehicle costing plays a central role in providing this link. The relationship is shown in Table 1.

If our decision making relies on accurate vehicle costing, we must have reliable data. But reliability is not the only impor tant criterion. To make the right decisions, the information upon which they are based should be available with a certain frequency, it should achieve the correct level of relevance and present an appropriate level of detail. It is also necessary to ensure a cost effective approach.

Frequency refers to the speed and timing of the information, relevance is concerned with the precise information we need to make the decision, and the level of detail relates to the degree of disaggregation which is necessary.

New technology offers the opportunity to collect more information, more quickly and this provides more evidence for our decision making. As I have shown in the previous articles, it is possible to use computers and electronic devices to assist in data collection and analysis. I have summarised some of the techniques which specifically relate to vehicle costing in Table 2.

We need to decide which of these solutions will provide the best combination of frequency relevance, level of detail, reliability and cost effectiveness.

If we choose a software package to analyse drivers' hours, mileage and fuel consumption, for example, this may supply very reliable, rapid and cost effective information which can be used as an input to our vehicle costs. But this will not include the maintenance costs, so perhaps the level of detail will be inadequate.

On the other hand, we could 3lect an overall vehicle costing ackage which presents deiiled reports of all the costs ssociated with the operation. ut the package may require irge inputs of data, and even'ally produce reports for the ecision maker which are out f date.

How are transport operators ble to choose the kind of techology which is appropriate to ehicle costing in view of these omplex relationships? The nswer almost certainly lies in le type of decision for which le costs are required.

If we need vehicle costs to stablish our tariffs then it is ssential to obtain reliable in)rmation which includes all le costs, but it may not be ecessary to obtain such in)rmation on a daily, or even a teekly, basis. Once a month tould be sufficient.

By contrast, if we need costs ) identify a vehicle which is erforming badly, we will reuire these at frequent in

tervals, to avoid incurring extra cost over a long period.

If the decision dictates the form of our information, this in turn will determine the technology which we employ to provide that information. One of the problems with the definition of appropriate technology for vehicle costing is the variation between companies. This applies to the size and the characteristics of the operation (ie, own-account, general haulage, etcetera).

This variation makes it difficult to specify an ideal system which is suitable to all companies. For this reason each company may be forced to adopt an evaluation of the alternatives, following a method similar to the one outlined above, define the decisions for which vehicle costs are required, establish the frequency, detail, relevance and reliability of the information needs, and thereby select the most useful technology (if any).

It is also worth stressing that any organisation will be constrained by financial limits, and the vehicle costing information used for decision-making will be collected within such limits.

In previous articles I have considered some of the significant cost centres, such as maintenance and fuel, and the kind of technology which is available to measure the costs associated with each. I will now examine the software packages which are designed to provide information on vehicle costs. The package most suited to your company will depend on all the factors which have been mentioned.

There are a number of software packages currently marketed by consultants, specialised software houses, vehicle manufacturers, transport operators and other agencies. Many are designed for operation on mini or micro computers and their costs are consequently related to the hardware requirements.

Typical micro applications will retail for around £2,000£4,000 for the software and around £4,000-£7,000 for the hardware. Packages for use on a mini computer are often more expensive, although a very large increase in data storage facilities may be obtained.

Although the input requirements will vary, many software suppliers claim that staff training will take about a day, and the system may be operated by someone with keyboard experience. From our research we have found that this may be a little ambitious: the complexity of the inputs may demand more comprehensive training and a longer period to learn the format. The increasing move towards more menu-driven systems will certainly reduce some of the difficulties which arose with the early packages.

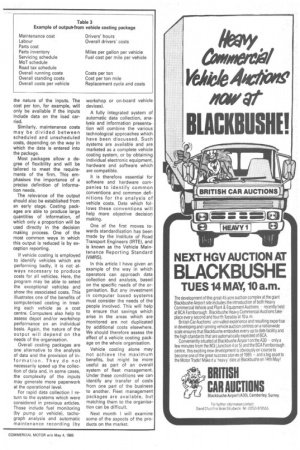

Table 3 provides an example of the output from a typical vehicle costing package. The level of detail and the frequency will vary according to the nature of the inputs. The cost per ton, for example, will only be available if the inputs include data on the load carried.

Similarly, maintenance costs may be divided between scheduled and unscheduled costs, depending on the way in which the data is entered into the package.

Most packages allow a degree of flexibility and will be tailored to meet the requirements of the firm. This emphasises the importance of a precise definition of information needs.

The relevance of the output should also be established from an early stage. Costing packages are able to produce large quantities of information, of which only a proportion will be used directly in the decision making process. One of the most common ways in which this output is reduced is by exception reporting.

If vehicle costing is employed to identify vehicles which are performing badly, it is not always necessary to produce costs for all vehicles. Here, the program may be able to select the exceptional vehicles and show the associated costs. This illustrates one of the benefits of computerised costing in treating each vehicle as a cost centre. Computers also help to assess depot and/or workshop performance on an individual basis. Again, the nature of the output will depend on the needs of the organisation.

Overall costing packages are one alternative to the analysis of data and the provision of info r mat io n . They do not necessarily speed up the collection of data and, in some cases, the complexity of the inputs may generate more paperwork at the operational level.

For rapid data collection I return to the systems which were considered in previous articles. Those include fuel monitoring (by pump or vehicle), tachograph analysis and automatic maintenance recording (by workshop or on-board vehicle devices).

A fully integrated system of automatic data collection, analysis and information presentation will combine the various technological approaches which have been discussed. Such systems are available and are marketed as a complete vehicle costing system, or by obtaining individual electronic equipment, hardware and software which are compatible.

It is therefore essential for software and hardware companies to identify common conventions and common definitions for the analysis of vehicle costs. Data which follows these conventions will help more objective decision making.

One of the first moves towards standardisation has been made by the Institute of Road Transport Engineers (IRTE), and is known as the Vehicle Maintenance Reporting Standard (VMRS).

In this article I have given an example of the way in which operators can approach data collection and analysis, based on the specific needs of the organisation. But any investment in computer based systems must consider the needs of the people involved. This will help to ensure that savings which arise in the areas which are monitored are not duplicated by additional costs elsewhere. We should therefore assess the effect of a vehicle costing package on the whole organisation.

Vehicle costing alone may not achieve the maximum benefits, but might be more useful as part of an overall system of fleet management. Under these conditions we can identify any transfer of costs from one part of the business to another. Fleet management packages are available, but matching them to the organisation can be difficult.

Next month I will examine some of the aspects of the products on the market.