Leyland's Constructor is Britain's top selling three-axle tipper and with

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

good reason, as Bryan Jarvis discovered when he tested it on and off the road

SINCE it introduced the Constructor in 1981 as a replacement for the ageing 6x4 Bison models, Leyland has continued to hold onto its lion's share of the three-axle tipper market. This has been in the face of some traditional competition from Bedford, Dodge and Ford as well as that of importers such as Mercedes-Benz, Scania and Volvo.

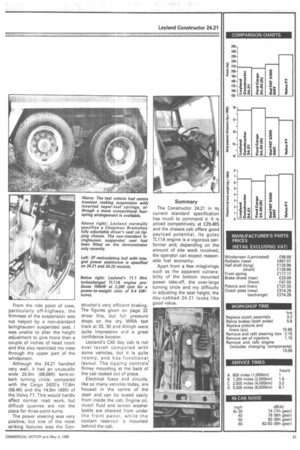

Last year, the entire 24-ton gross vehicle weight tipper market sector totalled nearly 5,800 units and Constructor models accounted for 2,167 of these. Sales of most of the remaining Super Mastiffs chassis increased this by a further 228 to bring Leyland's share to 42 per cent.

The company's tenure of this coveted position is no mere fluke. With its low 6,569kg (6.47 tons) kerbweight the Constructor 24.21 chassis cab offers a very generous body payload allowance of 17,820kg (17.54 tons). Only the leaner Deutz engined 24.20 Ford Cargo betters that, by 162kg (3.2cwt), Both are some way ahead of two close rivals the Daf FAT2300DHT with its 17,210kg (16.94 tons) body payload potential, and the Volvo F7 which gives slightly less at 17,040kg (16.77 tons).

Two wheelbases are available on Constructor models. The longer 5.0m (16.4ft) will accept bodies up to 6.1m (20ft).

But operators will not buy a vehicle purely on body payload potential. The vehicle needs to be moderately priced, a lively yet thrifty performer, easily maintained and backed up by dedicated after-sales support.

While many of the importers have made up ground on Leyland in recent years with the quality of their service back-up, there is no doubt about the 24.21's competitive price tag (vat _excluded) of £29,485, nor Leyland's very comprehensive Co-Driver support package. This is built on the 159 dealers and distributors throughout Britain and the Irish Republic which carry spares for the 145 range, and which in turn are supported by the "next working day" Multipart spares service.

Certainly the Constructors' performance is well up to expectation, with the familiar TL11A power unit showing a marked degree of flexibility and good acceleration.

Our test vehicle, a well run-in demonstrator with 38,000kms (23,750 miles) on the clock, had a number of changes in specification compared with a similar Constructor model tested three years ago (CM May 15, 1982).

Instead of the long-serving Fuller RT609, Leyland now offers the Eaton RTX6609 ninespeed range change box with a 0.77 to 1 top gear as standard.

Three axle ratios, 5.555, 6.250 and 6.933, are available; the 24.21 under test had the former.

The resulting difference in gearing between this and the previously tested Constructor allowed a maximum geared speed of 101km/h (63mph). This is sufficient to permit cruising on the motorway at the maximum 60mph with the engine running at 2,250rpm.

Leyland's 11.1 litre turbocharged engine seemed to be more than capable at 24-tons, producing 156kW (209hp) net at 2,200rpm for a power-to-weight ratio of 6.4kW/tonne (8.7hp/ton). rndeed, the TL11 engine can perform at this and higher weights, which is why Leyland specifies it in 220,238 and 260 gross horsepower ratings between 24.39 and 35 tonnes for Constructor and Cruiser models.

Over the 164 kms (102 miles) of our tipper route, which included 45 kms (28 miles) of typically tough site work, the 24.21 returned an overall fuel consumption of 48.21 lit/100km (5.86rnpg) at a fairly high 39.39km/h (24.48mph) average speed.

This was a drop in performance since the earlier Constructor test, from 40.3km/h (25.02mph) and 40.94 lit/100km (6-9mpg). It was certainly much quicker but thirstier than the Volvo F7 (CM May 30, 1981) which returned 36.88 lit/100km (7.66mpg) at a slower. 37.50km/h (23.3mph) overall average speed.

Last year the Deutz-powered Ford Cargo 2420 covered the same route at 39.86km/h (24.88mph) and returned 44.0 lit/100km (6.42mpg).

As an indication of the fuel return that can be expected with only a minimum of site work, the 196km (122 mile) journey between the Motor Industry Research Association at Nuneaton and our tipper route at Bagshot in Surrey produced much better figures. This was mainly motorway and duel carriageway running. Using the usual tank-top testing procedure the 24.21 returned 33.75 lit/100km (8.37mpg) at an overall average speed of 65.3km/h (40.5mph).

This is probably an indication of the severity of our 3.5 mile off-road section which we visit on each of the 21 km (13 mile) circuits where continual gear changing and high engine speeds push the fuel consumption up considerably. This part of the exercise really highlights the vehicles' strengths and weaknesses.

With such a broad spread of gear ratios available I was able to keep in the high ranges on all but the steep gradients. The worst hill steepens suddenly and while the bumpy, twisting track is busy testing the suspension and steering, a very quick downward change is needed. Here, skipping from fifth to third gear gave the best result providing it was carried out at a high road speed. Any hesitancy inevitably brought the vehicle to rest.

Towards the end of the test it became apparent that my technique was not so much lacking but that the clutch pedal had gradually become very spongy. This called for an occasional double declutch and an agility on the pedals which is not nor mally necessary.

Whether hurrying along rutted site roads or climbing across deep tracks, the rear bo gie suspension coped extremely well. The standard twospring (one each side) arrangements differ from the conventional four-spring option in that the two-leaf springs are inverted and rock on centre trunnions.

From the ride point of view, particularly off-highway, the firmness of the suspension was not helped by a non-standard lsringhausen suspended seat. I was unable to alter the height adjustment to give more than a couple of inches of head room and this also restricted my view through the upper part of the windscreen.

Although the 24.21 handled very well, it had an unusually wide 20.9m (68.68ft) kerb-tokerb turning circle, compared with the Cargo 2420's 17.8m (58.4ft) and the 14.9m (49ft) of the Volvo F7. This would hardly affect normal road work, but difficult quarries are not the place for three-point turns.

The power steering was very positive, but one of the most striking features was the Con