• Road Haulage Supreme in Ireland Northern

Page 48

Page 49

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

THE detailed clauses which the Government of Northern Ireland intends to insert in the Motor Vehicles and Road Traffic Bill, now before the Ulster House of Commons, are likely to differ substantially from legislation introduced elsewhere to organize commercial road transport. The reason is that transport conditions in Northern Ireland are singularly affected by the small area which they cover.

The territory open to the motorvehicle operator is only about 5,000 sq. miles. Such an independent country, on account of the comparatively small area that it comprises, is particularly suited to the development of mechanical road transport.

Road-haulage Expansion.

As a result, the road-haulage industry in Ulster has expanded to a greater extent than in most larger countries, and the Government is now attempting to organize goods transport, as a whole, on the most economic and efficient basis.

Parliament is, however, fully aware of the far-reaching effects which will attend its decision, and is waiting for the recommendations of Sir Felix Pole, who will inquire, early in May, into the conditions of Ulster's transport The Government is also in a position to draw its conclusions from the working of the road and rail co-ordination Act of the Irish Free State and the licensing system established in Great Britain.

The railway companies of Ulster are anxious that a scheme of road and rail co-ordination should be 'in n34 troduced, which would empower them to take control of all goods transport within the areas that they serve. Such an Act came into force in the Irish Free State at the beginning of the year.

Should the Ulster Government introduce a similar system, it would have to invest the railway companies with power to acquire businesses by compulsion and, of course, guarantee loans to the companies to carry out the scheme.

Hauliers, on the other hand, demand the right to carry on their services as before, and request only that the proposals of the Bill shall provide legal protection from unfair and uneconomic competition. To further this end, they press for the issue of haulage licences on the area principle, a wages and hours 'clause for employees, and, if necessary, a goodstransport tribunal similar to that now in existence for the regulation of road passenger carrying. The hauliers are being supported in their proposals by the majority of traders and business men concerned with transport.

It has been advanced in some quarters that the railways are a national necessity and, as such, should be given preference in the matter of 'both road and rail trans

port. In Ulster, it is clear that this view of the importance of the railways is by no means true to fact.

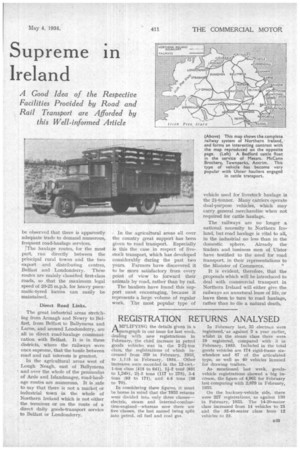

Bearing in mind that the most remote point in Ulster is less than a sixhour journey from Belfast 'by the ordinary type of heavy lorry, we may understand the exact position of the railways in relation to goods transport by comparing the two maps reproduced herewith,

Coastal Haulage Routes.

With the exception of the towns of Londonderry and Coleraine, Belfast and Lame, and Belfast and Bangor, there are no two coastal towns of any size directly in rail communication. Yet there is scarcely a three-mile stretch of coastline in the whole of Northern Ireland which has not a main haulage route hugging it.

Moreover, apart from the central area between Omagh, Dungannon and Dungiven, and the districts around Ballnahinch and between Ballymena, 13allycastle and Larne— which are all mountainous and, therefore, outside our consideration —there are many wide gaps through whh no railway runs. Conspicuous gaps are the Ards and Islandmagee Peninsulas, the country north-west of Newry and that east of Ballymena. Within all these gaps, however, it can be observed that there is apparently adequate trade to demand numerous, frequent road-haulage services.

The haulage routes, for the most part, run directly between the principal rural towns and the two export and distributing centres, Belfast and Londonderry. These routes are mainly classified first-class roads, so that the maximum legal speed of 20-25 m.p.h. for heavy pneumatic-tyred lorries can easily be maintained.

Direct Road Links.

The great industrial areas stretching from Armagh and Newry to Belfast, from Belfast to Ballymena and Larne, and around Londonderry, are all in direct road-haulage communication with Belfast. It is in these districts, where the railways were once supreme, that the tussle between road and rail interests is greatest.

In the agricultural areas west of Lough Neagh, east of Ballymena and over the whole of the peninsulas of Ards and Islandmagee, road-haulage routes are numerous. It is safe to say that there is not a market or industrial town in the whole of Northern Ireland which is not either the terminus or on the route of a direct daily goods-transport service to Belfast or Londonderry. In the agricultural areas all over the country great support has been given to road 'transport. Especially is this the case in respect of livestock transport, which has developed considerably during the past two years. Farmers have discovered it to be more satisfactory from every point of view to forward their animals by road, rather than by rail.

The hauliers have found this support most encouraging, because it represents a large volume of regular work. The most popular type of vehicle used for livestock haulage is the 21--tonner. Many carriers operate dual-purpose vehicles, which may carry general merchandise when not required for cattle haulage.

The railways are no longer a national necessity to Northern Ireland, but road haulage is vital to all, in the industrial no less than in the domestic sphere. Already the traders and business men of -Ulster have testified to the need for road transport, in their representations to the Minister of Commerce.

It is evident, therefore, that the proposals which will be introduced to deal with commercial transport in Northern Ireland will either give the railways an unnatural lease of life, or leave them to turn to road haulage, rather than to die a natural death.