(41 w or(rJ) CM'S loss of licence campaign focuses on

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

a driver who had a DVLA compensation offer withdrawn, and others who have benefitted from relaxed epilepsy regulations. Driving licence watchdog the DVLA did the dirty on a truck driver by Uturning on a promise to pay him compensation.

And this is the second time that the DVLA has played fast and loose with his livelihood.

Last September it promised to pay the West Country owner-driver loss of earnings compensation for temporarily withdrawing his LGV licence because of a suspected heart condition years earlier. By November it had reversed that decision.

This was confirmed to driver Peter Nickell's solicitor in a letter, containing the words: "concluded that an element of compensation is in order".

The letter went on to state: "We will therefore be contacting you in the next few days with an offer of what we consider to be appropriate in the circumstances." It was signed by Michael Rossell, the DVLAs head of driver policy and development.

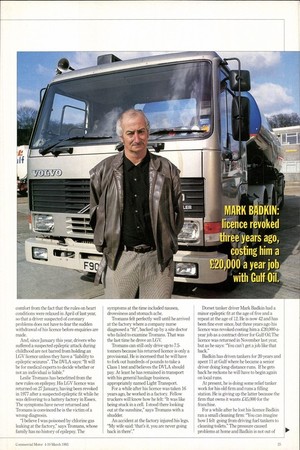

Nickell's licence was revoked without warning in November 1991 because of a suspected heart condition in 1980 and not returned until April 1992.

Nickell won his licence back and £1,000 costs after a court battle, but he was still £6,000 the poorer for loss of earnings.

Despite a steady stream of letters from Nickell's solicitor, requesting details of the compensation, no firm reply was forthcoming for a lengthy period of time from the DVLA.

Finally a letter arrived from the agency in November from Martyn Ford, legal adviser at the DVLA saying "I can advise you that careful consideration has been given to your client's claim for compensation. However, the decision is that no offer of compensation should be made."

TURNABOUT Explaining the reason for the turnabout, Ford referred Christopher Over to an obscure 1988 case, Jones vs Department of Employment, which Over says "does not apply in this instance".

"It is remarkable to have a letter from a government department offering compensation only to have that offer rescinded by someone else in the same department," says Over, who is determined not to let the matter rest.

Michael Rossell at the DVLA says he acted in good faith when he made the offer to Nickell's solicitor, but admits: "I was subsequently proved to be wrong.

"When I wrote my letter we were of the view that compensation was payable, but subsequent legal advice proved this was not so," says Rossell, adding "Legal advice does change, as you well know."

Rossell sympathises with Nickell's enormous disppointment at the DVLAs Uturn, but denies that compensation was withdrawn because the DVLA feared a tidal wave of similar claims if a precedent was set. "Each case is treated on its merits," he insists.

Drivers like Nickell can belatedly take comfort from the fact that the rules on heart conditions were relaxed in April of last year, so that a driver suspected of coronary problems does not have to fear the sudden withdrawal of his licence before enquiries are made.

And, since January this year, drivers who suffered a suspected epileptic attack during childhood are not barred from holding an LGV licence unless they have a "liability to epileptic seizures". The DVLA says: "It will be for medical experts to decide whether or not an individual is liable."

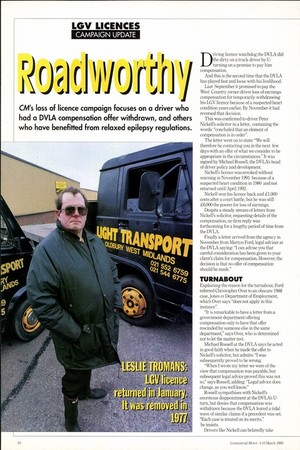

Leslie Tromans has benefitted from the new rules on epilepsy. His LGV licence was returned on 27 January, having been revoked in 1977 after a suspected epileptic fit while he was delivering to a battery factory in Essex. The symptoms have never returned and Tromans is convinced he is the victim of a wrong diagnosis.

"I believe I was poisoned by chlorine gas leaking at the factory," says Tromans, whose family has no history of epilepsy. The symptoms at the time included nausea, drowsiness and stomach ache.

Tromans felt perfectly well until he arrived at the factory where a company nurse diagnosed a "fit", backed up by a site doctor who failed to examine Tromans. That was the last time he drove an LGV.

Tromans can still only drive up to 7.5tonners because his returned licence is only a provisional. He is incensed that he will have to fork out hundreds of pounds to take a Class 1 test and believes the DVLA should pay. At least he has remained in transport with his general haulage business, appropriately named Light Transport.

For a while after his licence was taken 16 years ago, he worked in a factory. Fellow truckers will know how he felt: "It was like being stuck in a cell. I stood there looking out at the sunshine," says Tromans with a shudder.

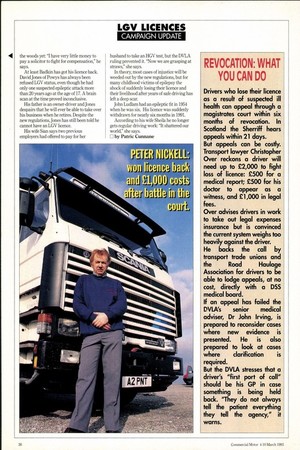

An accident at the factory injured his legs. "My wife said: 'that's it, you are never going back in there'." Dorset tanker driver Mark Badkin had a minor epileptic fit at the age of five and a repeat at the age of 12. He is now 42 and has been fine ever since, but three years ago his licence was revoked costing him a £20,000-ayear job as a contract driver for Gulf Oil.The licence was returned in November last year, but as he says: "You can't get a job like that back."

Badkin has driven tankers for 20 years and spent 11 at Gulf where he became a senior driver doing long-distance runs. If he gets back he reckons he will have to begin again on local runs.

At present, he is doing some relief tanker work for his old firm and runs a filling station. He is giving up the latter because the firm that owns it wants £45,000 for the franchise.

For a while after he lost his licence Badkin ran a small cleaning firm: "You can imagine howl felt going from driving fuel tankers to cleaning toilets." The pressure caused problems at home and Badkin is not out of the woods yet: "I have very little money to pay a solicitor to fight for compensation," he says.

At least Badkin has got his licence back. David Jones of Powys has always been refused LGV status, even though he had only one suspected epileptic attack more than 20 years ago at the age of 17. A brain scan at the time proved inconclusive.

His father is an owner-driver and Jones despairs that he will ever be able to take over his business when he retires. Despite the new regulations, Jones has still been told he cannot have an LGV licence.

His wife Sian says two previous employers had offered to pay for her husband to take an HGV test, but the DVLA ruling prevented it. "Now we are grasping at straws," she says.

In theory, most cases of injustice will be weeded out by the new regulations, but for many childhood victims of epilepsy the shock of suddenly losing their licence and their livelihood after years of safe driving has left a deep scar.

John Ludlam had an epileptic fit in 1954 when he was six. His licence was suddenly withdrawn for nearly six months in 1991.

According to his wife Sheila he no longer gets regular driving work: "It shattered our world," she says.

by Patric Cunnane