The number of truck manufacturers in Europe has fallen from

Page 46

Page 47

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

around 100 to 10 or so in less than 50 years—while the diversity and complexity of the vehicles they build has increased 1,000-fold. Gibb Grace looks at how the surviving manufacturers are responding to these market pressures.

Henry Ford was not the first to use production-line techniques—the concept originated in the food processing industry—but he was the first to exploit them fully.

In 1913, Model T production was transferred to a moving line. Within a year the build time fell from twelve-and-a-half hours to one hour, thirty three minutes, giving the company a massive price advantage that put it years ahead of its rivals. By 1916 Ford was building half-a-million cars a year.

Truck manufacturers fully understood these lessons, but their products were more varied than Ford's and their volumes were much, much lower. The process of building many types of high-quality trucks, profitably, in relatively small numbers has taken years to perfect. Profitable manufacturing is a fine balance between investment and production level: big investment and small production runs equal high prices. This forces manufacturers to restrict investment and compromise the product in some way, or grow fast enough to boost production to the point where the larger investment pays off.

Development costs can be cut by buying in products from suppliers as opposed to making them in-house. This "make or buy" decision is usually based on a cost/benefit argument. It is generally clear cut in the case of components such as windscreens, tyres and batteries—but less so with chassis frames, axles, wiring looms or cab trim and seats.

And when it comes to cabs and drivelines, which are critical factors for most customers, logic often goes out of the window and manufacturers can end up making parts which would be cheaper to buy in.

Improving product quality, while expanding the range and attempting to reduce manufacturing costs, exercises some of the best brains in the business. Iveco, for example, was formed by combining the resources of Fiat, OM and Lancia in Italy, Unic in France, Magirus in Germany, Ford in the UK and Pegaso in Spain. This was a way of reaching critical mass quickly and assembling a larger manufacturing base. But it cost £2.5bn—the largest investment ever made in Europe—to rationalise the manufac turing plants across five countries, and the vehicles they produce.

And with the recent closure of the Langley plant, it is clear that the process can go on.

Priorities Other manufacturers had different priorities. As late as 1950, for example, Scania was building just 1,500 units a year, mainly for its home market. It progressively rationalised components throughout the fifties, sixties and seventies, introducing its first rationalised range in 1980. This approach, masterminded by Carl-Bertel Nathorst, was refined with the 3-Series in 1988 and the Streamline in 1991, culminating with the 4-Series in 1995.

Today Scania is a global company producing 45,000 trucks a year, 95% of which are exported.

This scale of change requires huge effort and is not without risk, but profitability improves as production becomes more flexible and better able to cope with customer demand. Common components also reduce the money tied up in stock while allowing higher availability.

In Scania's case this allows its customers to specify the exact vehicles they need to suit their operations, while Scania achieves costefficient use of its research and production resources.

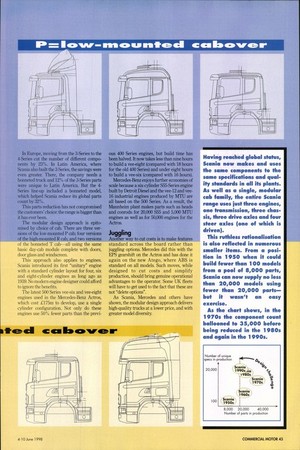

Scania has not only reduced its parts count in Europe: now the rationalisation process is complete in Latin America, the global savings are significant too. In Europe, moving from the 3-Series to the 4-Series cut the number of different components by 23%. In Latin America, where Scania also built the 3-Series, the savings were even greater. There, the company needs a bonneted truck and 12% of the 3-Series parts were unique to Latin America. But the 4Series line-up included a bonneted model, which helped Scania reduce its global parts count by 32%.

This parts reduction has not compromised the customers' choice: the range is bigger than it has ever been.

The modular design approach is epitomised by choice of cab. There are three versions of the low-mounted P cab; four versions of the high-mounted R cab; and two versions of the bonneted T cab—all using the same basic day-cab module complete with doors, door glass and windscreen.

This approach also applies to engines. Scania introduced its first "unitary" engine with a standard cylinder layout for four, six and eight-cylinder engines as long ago as 1939. No modern engine designer could afford to ignore the benefits.

The latest 500 Series vee-six and vee-eight engines used in the Mercedes-Benz Actros, which cost £175m to develop, use a single cylinder configuration. Not only do these engines use 50% fewer parts than the previ ous 400 Series engines, but build time has been halved. It now takes less than nine hours to build a vee-eight (compared with 18 hours for the old 400 Series) and under eight hours to build a vee-six (compared with 16 hours).

Mercedes-Benz enjoys further economies of scale because a six-cylinder S55-Series engine built by Detroit Diesel and the vee-12 and v 16 industrial engines produced by MTU all based on the 500 Series. As a result, th Mannheim plant makes parts such as heads and conrods for 20,000 S55 and 5,000 MTU engines as well as for 50,000 engines for th Actros.

Juggling Another way to cut costs is to make features standard across the board rather than juggling options. Mercedes did this with the EPS gearshift on the Actros and has done it again on the new Atego, where ABS is standard on all models. Such moves, while designed to cut costs and simplify production, should bring genuine operational advantages to the operator. Some UK fleets will have to get used to the fact that these are not "delete options".

As Scania, Mercedes and others have shown, the modular design approach delivers high-quality trucks at a lower price, and with greater model diversity. Having reached global status, Scania now makes and uses the same components to the same specifications and quality standards in all its plants. As well as a single, modular cab family, the entire Scania range uses just three engines, one transmission, three chassis, three drive axles and four steer axles (one of which is driven).

This ruthless rationalisation is also reflected in numerous smaller items. From a position in 1950 when it could build fewer than 100 models from a pool of 8,000 parts, Scania can now supply no less than 20,000 models using fewer than 20,000 parts— but it wasn't an easy exercise.

As the chart shows, in the 1970s the component count ballooned to 35,000 before being reduced in the 1980s and again in the 1990s.