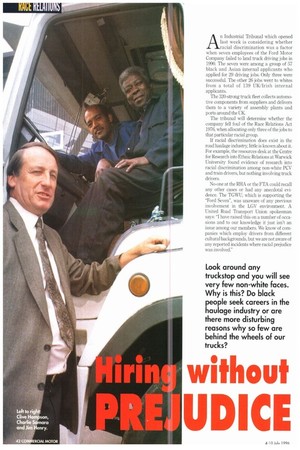

Look around any truckstop and you will see very few

Page 44

Page 45

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

non-white faces. Why is this? Do black people seek careers in the haulage industry or are there more disturbing reasons why so few are behind the wheels of our trucks?

An Industrial Tribunal which opened last week is considering whether racial discrimination was a factor when seven employees of the Ford Motor Company failed to land truck driving jobs in 1990. The seven were among a group of 57 black and Asian internal applicants who applied for 29 driving jobs. Only three were successful. The other 26 jobs went to whites from a total of 139 UK/Irish internal applicants.

The 320-strong truck fleet collects automotive components from suppliers and delivers them to a variety of assembly plants and ports around the UK.

The tribunal will determine whether the company fell foul of the Race Relations Act 1976, when allocating only three of the jobs to that particular racial group.

If racial discrimination does exist in the road haulage industry, little is known about it. For example, the resources desk at the Centre for Research into Ethnic Relations at Warwick University found evidence of research into racial discrimination among non-white PCV and train drivers, but nothing involving truck drivers.

No-one at the RHA or the FTA could recall any other cases or had any anecdotal evidence. The TGWU, which is supporting the Ford Seven", was unaware of any previous involvement in the LGV environment. A United Road Transport Union spokesman says: "I have raised this on a number of occasions and to our knowledge it just isn't an issue among our members. We know of companies which employ drivers from different cultural backgrounds, but we are not aware of any reported incidents where racial prejudice was involved." Perhaps this is because white UK/ Irish LGV drivers ,o often criticised for their poor behaviour with regard to women in the workplace—are infinitely more tolerant of non-white colleagues.

Chris Myant, a spokesman for the Campaign for Racial Equality, offers a more plausible reason. "You will not get complaints about racial discrimination until there are sufficient numbers of black people in the industry." There are fewer entry points to the industry for non-whites, he says. For example, the industry recruits large numbers of LGV drivers from the armed forces, who either get their licence in service or receive training as part of a re-settlement course. A low ethnic mix in the armed forces could leave this door of entry shut.

Personal contacts

Steve Hart is a TGWU regional officer for the automotive group and involved in the Ford Seven case. "In the truck industry, a large proportion of job applicants come through personal contacts, particularly where smaller employers are concerned. This might be more the issue rather than a question of fair or open selection." Chris Myant at CRE says discrimination is not always intentional: "Indirect discrimination can arise when an employer has a workforce from one ethnic group when a significant percentage of the people in the area are from a variety of ethnic groups. If job availability is advertised verbally, some of these groups are unlikely to hear about them."

In a small company, if the majority of the drivers are white and a job comes up, it is inevitable that the white people they mix with will get to hear about the vacancy first, says Clive Hampson, a director at Birminghambased Hampson Haulage, which is also a member of the RHA. However, he has two experiences to the contrary: "We advertised for a fitter in the local press, but one of the white drivers lived in the same street as a Jamaican chap who was out of work and told him about the vacancy. He was the only nonwhite of all the applicants and he had the best qualifications."

Charlie Samara is a Kenyan-born driver who has been on the Hampson staff for about 13 years. "We got Charlie by word of mouth. The manager we had at the time had worked with him and knew he was a good driver. We pinched him from another company. It just so happens that in both cases, we recruited someone who was black who was recommended by someone who was white."

Samara is quick to scotch any notion that few non-whites would relish a career driving LGVs, but confirms the apparent institutional view that problems of racial prejudice are rare for the few non-white drivers. "I've never experienced any problems related to the colour of my skin. My brother-in-law who drives a bus had a problem or two for a while, but perhaps I'm lucky. I'll talk to anyone. It doesn't matter to me what colour they are." Errol Smikle describes himself as AfroEnglish. He has been a truck driver for eight years. Like many of his truck-driving colleagues, he paid for his own LGV driving lessons and test before gaining experience with driver agencies. He now drives for NFC's Exel Logistics, having moved across from BRS Taskforce.

He has had no racial problems at any of the companies he has worked for, but suggests there may be some underlying prejudices within the induStry as a whole: "For example, although I see more and more black drivers on the road, very few drive artics and I've never ever seen a black driver behind the wheel of a tanker, a job considered as the cream of the driving jobs." Chris Myant at CRE agrees but says that it is ocit necessarily a result of deliberate racism and companies would be horrified to learn that their recruitment practices could be interpretcal as racist.

The CRE's Code of Practice was adopted by Parliament in Ng. Its guidelines help companies comply and while it is not a law in itself, ignoring it can lae a breach of the law. A few years ago, a leading utility was berated at an industrial tribunal when several managers claimed in evidence to have read the code, but could not remember anything about it, even its size or the colour of the cover.

"They had not committed any crime, but it was considered tut cceptable for senior managers of such an established high-profile company not to have been familiar with its contents," says Myant.

Identified quickly

In recent years companies have had to take firm stands to ensure that discrimination, whether racial or gender-based, is identified quickly and dealt with swiftly. NFC's Teamwork Through People initiative is an example more advanced than most. Its policy statement declares the need for a "non-discriminatory and harassment-free working environment".

All employer are given a copy and about 120 volunteers have gone through a counsellors' course to Ix able to help any NFC employees who believe they are being discriminated against because of their race, or sex. They also staff a supporting telephone helpline.

RACE AND RECRUITMENTGETTING THE BALANCE RIGHT

1 . Be conscious and aware ti problems can arise in the wor Many incidents occur as a re.1 existing practices. For examp advertising by word of mouth than by using the local press lead to discrimination. Job ce or colleges of further etlucati might be a source of recruit.

2. If the size of the company it sensible, monitor the ethrin of the employees. Is the etlin appropriate to that found in region in which the company operates?

Never positively rhscrimin order to boost the ethnic mi is in itself a form of thscrimin However, reaching into the community is one way of attr candidates from wider cultur bacisgrounds.