Redlands decentralized transport

Page 101

Page 102

Page 103

Page 104

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

THE road transport function in any diversified manufacturing organization is obviously important: in an international group as large as Redland Ltd.. which has nearly 1,400 vehicles and a combined turnover of some .£60m, the economical and efficient organization of transport is of crucial importance. For most of the group's products are heavy and—for their weight—of relatively low cost.

When the unit cost of products is high transport costs as a proportion of turnover do not have to be examined so stringently.

In the competitive trading conditions applying in the building and constructional indus tries efficient transport arrangements are of major commercial importance. In this field. as in so many others, customer education can greatly help transport economy.

Redland's transport operations cover such a wide field that a close look at a small sample of activities is not necessarily rep resentative of the whole transport set-up. The stress is on decentralization with the maximum authority concentrated on operational points and a degree of central guidance from headquarters. Even if, to the outsider, the pattern looks somewhat untidy it is still a pattern that works.

In my visits to the headquarters of Redland Transport Ltd., and to plants making tiles, bricks and pipes. the importance attached to efficient road transport operation became evident. In the management of the transport function in Redland there is a valuable blend of professional transport expertise with the customer-oriented transport thinking common to most own-account operators.

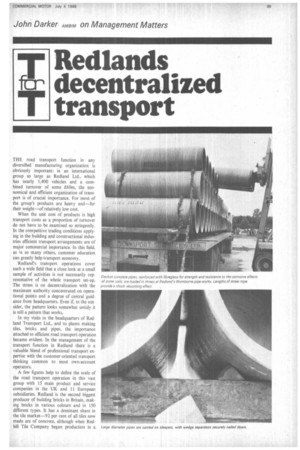

A few figures help to define the scale of the road transport operation in this vast group with 15 main product and service companies in the UK and 11 European subsidiaries. Redland is the second biggest producer of building bricks in Britain, mak ing bricks in various colours and in 150 different types. It has a dominant share in the tile market-92 per cent of all tiles now made are of concrete, although when Redhill Tile Company began production in a Reigate sandpit in 1919 the concrete tile was an innovation.

Today, the firm's tile plants produce about 1,000 tiles a minute, some 550m tiles annually. The number of vehicle loads represented by the millions of square yards of tiling laid a year can be imagined.

Mr. E. J. Peacock, chairman of Redland Transport Ltd., has a long experience as a professional transport operator—surely a good grounding for any manager of an own-account fleet which hires substantial numbers of vehicles. Redland Transport owns all the vehicles operated by subsidiary companies and arranges for their licensing and insurance and for much of their maintenance and overhaul.

There are 15 Redland repair centres, with two major workshops near Sevenoaks and Rugby. The distinctive livery of the company is a commercial asset and it would be difficult to fault the vehicle maintenance philosophy of the group—Redland's own roving examiners make independent checks at any time or place and have full authority to put any suspect vehicle off the road.

Redland Transport advises member firms on the effects of the Transport Act and other legislation, holding regular meetings with divisional transport managers. The company undertakes rate and weight calculations for tile and pipe haulage. The Reigate computer-equipped accounts office produces an overall operating statement for the transport function in the group, and results are carefully monitored.

Variety Mr. Peacock stressed the great variety of work undertaken by the constituent companies. On the quarry and processing side Redland-lnns Gravel Ltd. was the largest member company with 26 pits throughout the country. Redland Quarries and J. Cross and Sons, other subsidiaries, have 15 pits.

It is not surprising that tipper vehicles are an important sector of the industry when it is realized that in 50 years the consumption of sand and gravel has soared from 2m tons to 110m-11Im tons in 1968.

The diverse operations of the brick, tile, sand and ballast and road-making sectors of Redland make vehicle standardization—as a concept—difficult to justify. Platform sizes of brick and tile vehicles may not coincide. Three or four leading makes of vehicles predominate. Redland has grown so rapidly as a result of an almost continuous acquisition of companies—in the last 13 years there have been 23 successful bids against three failures or withdrawals—that it would clearly be stupid to scrap a newly acquired modern fleet of a member company. Some vehicles have an eight-year life; others much less.

Redland Transport aims to make the best use of the capital invested in the vehicles and maintenance facilities. The problem, all through the years, has been to "digest" a constantly expanding fleet of variegated vehicles, good, bad and indifferent. Considering that Redland operated a mere five vehicles when Mr. Peacock first joined the firm, one can fully appreciate the point.

The efficiency of transport operations in many of the trades served by Redland member companies can be greatly helped by an increased awareness on the part of customers of the benefits of mechanical handling. These benefits, of course, are mutual. Transport operators are often prepared to provide costly equipment for mechanical loading and off-loading but the rate of advance on this front does greatly depend on customer co-operation.

In talks with transport executives in the Group I concluded that much more should be done through trade associations na promote co-operation between road hauliers and their customers. In the building and civil engineering trades this seems to me to be of paramount importance. The slow progress achieved so far indicates the great potential for improvement, Mr. Peacock has paid many visits to Holland, France and Germany to observe the mechanical handling techniques in use.in trades served by Redland and he stressed his hopes that the building industry in Britain would become increasingly receptive to the introduction of similar techniques.

He instanced Redland's introduction of the Hub o Track-liner system at the Horsham Brickworks. Steerable-axle 30T g.v.w. artic vehicles carrying 17 ton loads could get onto many sites without difficulty and the small premium charged for the much quicker mechanical off-loading of the specially packed brick-stacks was increasingly accepted by customers.

"In Germany", said Mr. Peacock, "where C-licensed transport has been virtually taxed out of existence, tower cranes at most building sites make the job of the professional haulier very much more economic. The fixed-rate structure also makes hauliers much more selective in the work they undertake. Here, it is seldom practicable to apply demurrage charges when vehicles are delayed on sites for an unreasonable period." (The "supply and demand" situation is, of course, a factor in the attitude of customers. When there is a national shortage of bricks, for example, it is more feasible to apply demurrage.) Mr. Peacock sees tremendous opportunities for more efficient operations as a consequence of the Transport Act. "Transport has been abused in the past, it must now become a recognized industry run on professional lines."

No common pattern I referred earlier to the absence of a common pattern of transport in the Redland group. At the Reigate headquarters of the pipes division Mr. Bill Abbey, production manager, is also functionally responsible for transport. He explained that the sales department.was responsible for getting orders but the delivery of the pipes to the site was traditionally a production function.

In the tiles division where transport was subordinate to the sales director the sales problems were very different. Pipe orders, as for example on a motorway contract, could call for deliveries several months hence, often to agreed time schedules, whereas a builder might order a supply of tiles to roof a pair of houses and want virtually immediate delivery.

Mr. Abbey said that his division made a wide range of pipes ranging from 6in. diameter 3ft long to 108in. diameter 4ft long. The smaller pipes were often moved four or six at a time by specially fitted fork-lift trucks. Large diameter pipes were handled at works and on site by mobile cranes. Site delivery problems, and hence vehicle turn-round, varied enormously.

On some contracts 40ft trailers could be used and on others short-wheelbase fourwheelers were accommodated with difficulty. The lack of suitable unloading equipment was a problem at many sites and Redland was studying possible methods. In a recent visit to the United States he had seen a good deal of advanced equipment and he would look favourably on any recommendations from his divisional transport manager for viable equipment that would justify its capital cost.

Mr. Abbey said that it was impossible to generalize and say that large contractors invariably turned round vehicles more quickly than small ones. This did not always happen and there were some small cus tomers who were so proud of turning round vehicles quickly that if, on a particular occasion, a Redland vehicle was delayed unduly, the customer would phone with profuse apologies.

Nation-wide delivery of pipes was from eight works, some specialized products be ing delivered to Scotland. Although produc tion was continuous, output was normally much higher between April and October.

Deliveries could run to 6,000 tons a week during the summer and less than half that in the winter. The base load was dealt with mainly by Redland vehicles, with con siderable hiring during peak periods. Because of the current difficulty in hiring Redland was having to increase its fleet of pipe-delivery vehicles. The production manager's transport responsibility included the loading of pipes onto vehicles at production sites and ended when deliveries were made. Drivers were responsible to the transport manager or transport supervisor based at the production plants. The general transport management responsibility in the pipes division rested on Mr. P. Bulmore, based in the East Midlands, -with whom he liaised closely.

Mr. Abbey said that all Redland pipe vehicles were at the moment rigids but articulation was being introduced at one works shortly. With transport costing about 9+ per cent of the delivered price of pipes cost control was vital; costs were tending to increase faster than in the past.

Although in many cases pipes were ordered by the vehicle-load, deliveries involv

ing two drops were quite common and it was occasionally necessary for drivers to make three deliveries with a single vehicle load. Mr. Abbey stressed that much of Redland's success lay in the fact that small customers were given an excellent delivery service. In the building and civil engineering industry some firms that were very small a decade ago were very substantial customers today. Redland, in fact, had grown with such customers. Perhaps there is a moral here!

Mr. Abbey stressed that there was a very friendly relationship between production and sales executives in the pipes division and regular discussions ironed out any difficulties relating to transport operations. Massive tonnages of bricks are moved by Redland and hired transport from the 24 brick works producing more than 1 1m bricks weekly. For many customers prompt deliveries cement the commercial relationship but at times of peak output a proportion of customers may choose to collect bricks with their own or a contractor's vehicle.

Wherever possible mechanical aids to loading are used, but in the smaller brickyards it would not be economic to employ costly equipment that could not be used intensively. The cost of bricks varies greatly with specification, some good quality bricks costing £20 or £30 per 1,000—several times the cost of commons, The more expensive types of brick demand more careful handling, with straw packing to minimize chipping and scuffing.

Several methods of brick stacking to facilitate mechanical handling have been tried and currently three methods are used in the Brick division. Changes in stacking patterns, of course, demand costly changes in production machinery so that patterns are not changed without good reason, and then infrequently. Banding of bricks—at one time thought to be the answer to many of the brick industry's transport problems —has not caught on with many customers. It demands proper site handling equipment, such as tower cranes or fork-lift trucks, and banding is done only at the special request of customers.

Special stacking

Vehicles fitted with Hub handling equipment have been introduced to meet the growing demand from some builders for mechanical off-loading. A special stacking pattern enables half-ton brick-stacks to be handled quickly and a neat stack can be made on site at a convenient place for the builder. An ingenious device enables the bottom layer of the stack to be lifted or set down.

Using the Hub Track-liner a load can be discharged from a 30ft platform vehicle by the driver alone within an hour. The drivers take a month or two to familiarize themselves thoroughly with the system's flexibility and rapidly become converts to this form of brick handling.

Brick divisional transport manager Mr. Tom Lawrence, who is responsible for 170 vehicles operated from brickyards in the South of England, Bedford and Peterborough areas, said he found driver recruitment very difficult in Sussex because of the proximity to light industry at Gatwick.. He was also concerned at the difficulty of getting a sufficient number of hired vehicles normally required for about a third of the output of the local group of brickyards.

Mr. Lawrence explained that brick vehicles returning from deliveries often called for loads at other factories in the Group. But in summer there was constant pressure on his department to get bricks Out of the yards. Backloading at such times would mean fewer outward loads —or more vehicles on the combined operation. At the local Warnham brickyard where loading was by hand from the kilns much expense would be involved if lorries were not available to load when required. If bricks had to be stacked on the ground awaiting vehicles and were loaded subsequently the additional cost would be considerable.

Mr. Lawrence is convinced that local workshops are essential where intensive transport operations proceed alt through the year. He lamented the inability of many garages to live up to their promises in giving reliable and economic service to transport operators.

As one who first entered road transport 23 years ago. selling his own small fleet of Contract A licensed vehicles to a company since acquired by Redland, Tom Lawrence is well versed in the ways of the industry. He reminded me that in Fletton brickyards collections by customers' vehicles were deprecated whereas in the Sussex and Dorking yards this was welcomed. In a recent period, Redland vehicles had carried 84 loads from local yards against 167 loads by hired haulage and 218 loads collected by customers. These figures illustrate the uneven coverage in road transport in particular areas of the country.

At Redland's Leighton Buzzard tile works I talked to Mr. Christopher McMichael, the recently appointed divisional transport manager responsible for the road transport operations at 12 tile production units. Mr. McMichael is another transport professional now serving with a trader's own fleet. After some years in management in British Road Services and in private enterprise road transport firms he was finding his new environment a stimulating challenge..fle saw his job as serving Redland customers in the best possible manner as regards transport.

Although customers could collect tiles at Leighton Buzzard with their own vehicles, said Mr. McMichael, this tended to be discouraged particularly if the customer wanted priority treatment at times when Redland's own or contract vehicles were being loaded. The interest of the general body of Redland customers was paramount, in this connection. At some Northern plants there was a big tradition of ex-works tile collections, I learned. Rate levels in the North and South were historically different and this was possibly a factor in the way the pattern had developed.

Many would agree with Mr. McMichael's comment that it would take a bunch of transport economists to analyse the reasons for the marked disparity in local transport rates in this country. In theory, the stringent safety requirements now operating should cause rates to level out throughout the country. It remains to be seen whether this will prove to be so.

I was surprised to learn from Mr. McMichael that a 1968 analysis highlighted the low incidence of what most transport managers would consider to be economic loads. The pattern showed that 19-ton loads amounted to a mere .2 per cent of all tile loads; 10-ton loads comprised 1.3 per cent of all tile consignments and 7.7 per cent of ordered loads were of 54 tons. Many builders order tiles for a pair of houses. The problem of making up efficient loads and scheduling vehicles for multiple deliveries is clearly a formidable one.

Rather naturally, there was a resistance on the part of many customers to the dropPing of full vehicle loads of tiles at one point on a site. Putting down small lots at several places on a large site obviously added to delivery costs. Some tiles were now being delivered in cages and this speeded up the loading and off-loading arrangements, given suitable equipment on sites. However, the return of the empty cages and their monitoring presented problems. Although crated tiles cost customers more and involved Redland in substantial extra costs a survey had shown that their use provided a favourable balance of extra vehicle revenue, against the additional costs involved.

I was most impressed with some of the analytical work by Redland's accountants and transport management in pin-pointing operational costs. Also remarkable were the highly detailed terms of reference presented to Mr. McMichael on his appointment. It is rare for transport managers to know precisely what their company expects of them. Clearly, Redland's top management under the dynamic leadership of the young managing director, Mr. C. R. Corness, is fully apprised of the key role of road transport and of the significant economies that can be made by the judicious use of mechanical handling aids.

Mr. McMichael showed me a fully illustrated survey of tilehandling equipment in use in Europe. This was prepared by Redland as a stimulus to management thinking and it illustrates admirably the group transport philosophy: if there is a better way of doing things, then do it; if there is doubt about a new method continue with traditional ways. Overall, transport policy is motivated by the needs of the cutomers. Their technical development and readiness to innovate is very uneven. As the British building industry gradually accepts the necessity for mechanization on small sites as well as large, Redland's diversified transport operations will be cheerfully "meshed in" with whatever site equipment becomes generally acceptable in the 70s.