Tanked up foe the egg tun...

Page 68

Page 69

Page 70

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

. . . Paul Illungo visits a liquid-egg transport depot, and found the process of transporting liquid eggs one of the most sophisticated kinds of transport in use.

IT TAKES about 400,000 eggs to fill one 4000-gallon road tanker, says Paul Marsh, transport manager of John Rannock Ltd, and that is important to him, because that is what John Rannock Ltd's business is all about.

Not eggs in their shells, of course. John Rannock Ltd are in the business of breaking eggs, collecting the liquid whites and yolks, and distributing them to large bakeries, biscuit manufacturers, and food processors.

Breaking eggs, normally a simple process usually done by inadvertantly dropping them on the floor, is accomplished at John Rannock by highly sophisticated machines that can break over half a million eggs a day.

It is one of only four or five plants in the UK that can carry out this highly specialised work.

For the transport manager, the first job is to collect the eggs and get them to the plant. About 200,000 a day are collected in two trailers, a 20footer and a 30-footer, from farms, egg packers, and other sources. The smaller trailer makes the circuit of the farms, doing between 15 and 20 pickups of probably 30 to 40 dozen eggs each time. The larger trailer will normally do one pickup, from a larger packer.

The eggs are called "second quality", which has absolutely nothing to do with their taste or freshness. Second quality eggs are eggs deemed "unsuitable for the general public" because of a misshapen or cracked shell, or blood specs on the yolk.

Another 15 to 20 tons of frozen egg melange comes across from the continent in unaccompanied trailers or containers. It arrives in the afternoon or evening, ready for processing the next day.

"The availability of eggs depends on their price", says Paul Marsh. "If the price in the shop is low, we have some trouble getting them. If the price is high, then it's no problem".

Processing eggs into a liquid is an assembly line job. Once they have been sorted onto a conveyor, they are carried to breaking machines where a little instrument like a hammer cracks them.

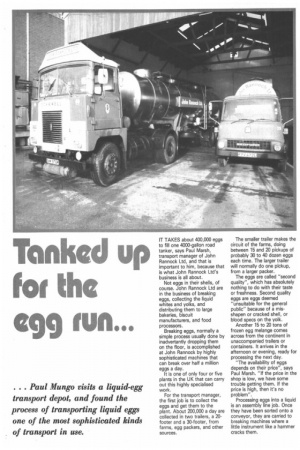

Facing page: One of the older ScammeII units, used for pulling the larger 4000-gallon tankers.

The yolk and the white iwhite is called albumen) can then be separated if necessary. When it is unseparated it is sold as whole egg and used by bakers or biscuit and cake manufacturers.

The liquid is pasturised, much the same as milk, and put in holding tanks to await shipment. The whole process takes between 24 and 36 hours, from the time the eggs arrive to the time they are distributed to the customers. In the production of the liquid, everything from the egg is used, except the shell.

"We could process the shells back into animal feed", explained the distribution manager, "but that's an expensive process and requires a lot of costly equipment. So for the time being we just tip them".

Because egg is one product very susceptible to contamination, the plant must comply with strict food regulations, particularly those related to personal hygiene.

Some of the machines, like the pastu riser, must have

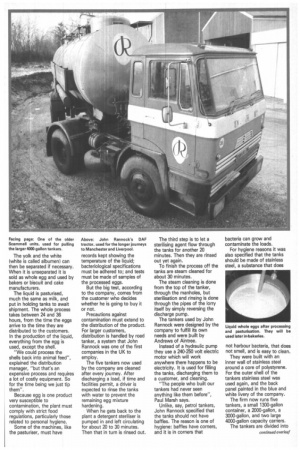

Above: John Rannocles OAF tractor, used for the longer journeys to Manchester and Liverpool.

records kept showing the temperature of the liquid; bacteriological specifications must be adhered to; and tests must be made of samples of the processed eggs.

But the big test, according to the company, comes from the customer who decides whether he is going to buy it or not.

Precautions against contamination must extend to the distribution of the product. For larger customers, distribution is handled by road tanker, a system that John Rannock was one of the first companies in the UK to employ.

The five tankers now used by the company are cleaned after every journey. After discharging a load, if time and facilities permit, a driver is expected to rinse the tanks with water to prevent the remaining egg mixture hardening.

When he gets back to the plant a detergent steriliser is pumped in and left circulating for about 20 to 30 minutes. Then that in turn is rinsed out. The third step is to let a sterilising agent flow through the tanks for another 20 minutes. Then they are rinsed out yet again.

To finish the process off the tanks are steam cleaned for about 30 minutes.

The steam cleaning is done from the top of the tanker, through the manholes, but sterilisation and rinsing is done through the pipes of the lorry itself by simply reversing the discharge pump.

The tankers used by John Rannock were designed by the company to fulfill its own needs and were !auk by Andrews of Aintree.

Instead of a hydraulic pump they use a 240-250 volt electric motor which will work anywhere there happens to be electricity. It is used for filling the tanks, discharging them to a customer, and cleaning.

"Tha people who built our tankers had never seen anything like them before", Paul Marsh says.

Unlike, say, petrol tankers, John Rannock specified that the tanks should not have baffles. The reason is one of hygiene: baffles have corners, and it is in corners that bacteria can grow and contaminate the loads.

For hygiene reasons it was also specified that the tanks should be made of stainless steel, a substance that does not harbour bacteria, that does not smell, and is easy to clean.

They were built with an inner wall of stainless steel around a core of polystyrene. For the outer shell of the tankers stainless steel was used again, and the back panel painted in the blue and white livery of the company.

The firm now runs five tankers, a small 1300-gallon container, a 2000-gallort, a 3000-gallon, and two large 4000-gallon capacity carriers.

The tankers are divided into

The pumping system, employing a 240-250 volt electric motor which can be used for loading, discharging and cleaning the tanks.

compartments to facilitate carrying different loads. The 4000-gallon containers, for instance, are split up into three separate vats, two with a capacity of 1000 gallons each, and one with a 2000-gallon payload.

Loading and discharging the egg is a complicated process because the yolk must not mix with the albumen, and viceversa. The motor pumps the substance into the vats from below, a process that avoids creating a froth on top of the liquid.

"If we loaded from the manhole", Paul Marsh explains, "by the time it was half full the froth would have reached the top of the tanker and we'd have to wait for it to subside". So the loading would take far longer, which no transport manager wants.

Complications come when two different liquids are being carried. To load one of the 4000-gallon tankers with both albumen and whole egg, the albumen has to be pumped into the middle vat first, so the pipes are not contaminated with any yellow. The whole egg, which of course contains albumen, can then be pumped into the remaining two tanks.

But because the pipes now contain some residue of the whole egg they would have to be cleaned before the load could be discharged; and that would have to be done in the same order: albumen first, followed by whole egg.

With two substances that can not be touched by each other the pipes have to be cleaned after each loading or discharging, a time-consuming process, but one which has to be clone.

"A very small amount of one product in the other", Paul Marsh says, "makes it unuseable. So we have to keep the pipes clean at all times".

It would cost, Paul Marsh estimates, almost E20,000 to replace the tankers and pumps. To avoid having to do so, the company has its own repair facilities that can do everything but body repairs" The delivery process begins at midnight with the loading of the tankers. Three go out at any one time, the 4000-gallon tankers to London pulled by older Scammells and another, pulled by a DAF, to either Manchester and Liverpool or Eastbourne.

If all goes well, they should be back in the depot by lunchtime. In the afternoon they are cleaned and sterilised, ready to go out again the next morning. "We've expanded the transport fleet as the business has grown", says Paul Marsh, remembering when he began with the company five and a half years ago. At that time they had only one large 4000gallon tanker; since then the firm has concentrated on maximum capacity vehicles, and expanded the fleet to its present size.

Further expansion will come with further business. Since the company began in 1934 it has grown to the extent that it covers the whole UK market.

The next step is Europe.

"After this year is through we hope to have met the EEC regulations and have received an EEC export licence. It will take us through 1977 to get the factory up to scratch, but once it is we'll start exporting to Europe".

The EEC regulations that have to be met are all to do with food hygiene and include processing requirements.

Expansion may not end even at the borders of the continent. "After we get Western Europe under our belts", says Paul Marsh with just a flicker of a grin, "then the sky's the limit".