CONTROLLING TRANSPORT OPERATION

Page 66

Page 67

Page 68

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

B.I. Transport Co Ltd by David Lowe, MInsTA, AMBIM

SO VAST is the empire of Ranks Hovis McDougall Ltd and so varied its range of products that in a booklet "The World of RHM" it is able to claim to be one of the world's largest food companies. Within this complex group of some 300operating companies the flour milling division forms a major activity and not the least of this division's preoccupations is the bulk movement of flour from its 20 mills. The sole responsibility for the movement of this flour rests with the transport subsidiary B.I. Transport Co Ltd, a 500-vehicle fleet whose director and general manager is Mr S. Phillips.

The prime function of B.I. Transport is to provide a transport and distribution service for 'the milling division, delivering all flour produced by the group, feedingstuffs not handled directly by customers and merchants and some grain and other raw materials. The decision on the means of transport to be used is taken by B.I. Transport; much of the traffic, in fact, is carried by the company's own vehicles or, where appropriate, by its lighterage fleet. The balance is subcontracted out but this is a difficult matter owing to the specialist nature of the traffic and the shortage of suitable bulk powder tankers available for spot hire.

The 500 vehicles operated by B.I. Transport are only a small proportion of the total group fleet of some 10,000 vehicles, several thousand of which are bread delivery vans. The B.I. Transport fleet consists solely of vehicles with a carrying capacity of 8 tons or more and these are either platform or bulk tanker types. An idea of the amount of traffic carried by B.I. Transport can be gained from the RHM claim that it makes 25 per cent of all bread eaten in the UK and supplies a large number of other users with its flour from its own mills.

The area covered includes Northern Ireland and the remote parts of Northern Scotland from 12 strategically placed depots attached to or near to major production points.

Control of this, the group's only specialist transport operation, is vested in Mr Phillips whose office is at the RHM centre on London's Thames Embankment and in his three subordinates, an assistant general manager, an assistant manager, and a chief engineer who are base,i, at theAroup's Management Services Centre at Harlow in Essex. From this centre the countrywide

transport operation is controlled and administered by these three executives, sharing an office to avoid departmentalization and its associated conflicts, and three admin sections dealing with operations, accounting and invoicing.

Transport operations at depot level are the responsibility of a transport manager whose exclusive duties are concerned with providing a service for the production point. In carrying out this function the transport manager has to work as a member of a closely knit management team consisting of' himself, the production manager and the commercial manager. It has been found by RHM that close consultation and co-ordination of the overall effort of a team of managers working together in this way leads to the provision of the most economical service. Decisions on whether or not to run uneconomical services are jointly taken but usually the transport manager points out the economics of the proposal and the final choice of whether or not to go ahead is a marketing decision.

Shaving margins The company has campaigned to make those staff not directly concerned with transport more aware of the factors which control transport costs .and particularly to show that while it may appear easy in some instances to shave margins off transport costs, care has to be taken that what is saved is not transferred to production costs. A particular case in point concerns bag loading which is a labour intensive activity and which has to be closely integrated to get the best efficiency of the total mill labour force. RHM, unlike many other companies which have ignored the problem, has made a conscious effort to bring much closer together all parties contributing to the efficiency of the enterprise.

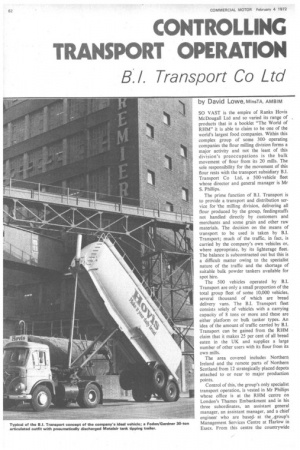

The operational advantages resulting from vehicle standardization is a subject which also has received no small degree of attention. The present policy for platform vehicles is to use primarily Foden /Gardner four-axle rigids and in the lighter range Dodge /Perkins 6.354 16-ton-gross rigids. The tanker fleet almost exclusively comprises Foden /Gardner rigids and tractive units operating at -26 and 30 tons gross with Metalair pneumatic tipping tanks built to the company's own specification.

Tank design is a special problem owing to the nature of the product carried and the facilities available at delivery points: In some instances insufficient headroom is available to allow tipping tanks. Progress in transport methods and vehicle design in these cases cannot be matched by progress in some areas of the baking industry.

Flour, I was told, has peculiar characteristics particularly when it is on the move and it is necessary to get a quick and clean discharge. It has to be aerated to move and be kept moving; tipping alone is not sufficient. The current design of tank in use with the snout-like rear end which provides a vertical wall effect inside when discharging under pressure, is the most efficient yet known to the company. Skill is needed in discharging and competent drivers can unload in 35 minutes. An unskilled man could take two hours. These flour tanks are considerably more expensive than those required for grain carrying so they are not used for any other purpose. Grain tanks are invariably non-tipping; discharge is normally through ground hopper and the tanks are not subject to the same critical weight problems as flour carrying. Maximum payload is easily achieved within a reasonably sized tank without excessive height.

The decision to opt for 30-ton maximum gross weight for the present was taken in the light of all the known operating factors such as stability, the type of engine preferred, 'general performance of the vehicles as a whole and the overall operating cost. An analysis of these factors showed 30 tons to be the optimum size at this time. Mr Phillips did hint that with the forthcoming increases in intermediate, gross weights within certain wheelbases the company would be looking at the possibility of operating 28 /30-ton-gross rigids within a 23ft wheelbase. At present it is operating at 26 tons gross within this length but an increase would involve some difficulty in getting sufficient tank capacity. Tanks have to be circular because of the pressure so the only course is to extend forward which means the use of underfloor tipping gear.

In the case of artics, 38 tons gross would suit if ever maximum gross weights were increased. A 24-ton payload should be possible, Mr Phillips thought, within this weight and this would fit in ideally with standard bakery silo storage modules of 48 tons. The present maximum carrying capacity of vehicles at approximately 16+ and 194 tons does not readily fit these modules.

B.I. Transport is looking for a minimum life of 10 years from its £12,000 Foden outfits and fully expects to get it. Mr Phillips believes that the best possible specification was chosen resulting in a most efficient, reliable and rugged vehicle admirably suited to the company's operational demands (most journeys are within 100 miles and speed is not of the greatest importance) with an economic performance which compares favourably with the alternatives.

It is conceivable that the very expensive tanks could have their life-span extended beyond that of the vehicle but the company considers that only a marginal advantage would be gained by bringing 10/12-year-old tanks up to date to fit new chassis. It is possible, however, that in the future owing to the very high cost of the current type of tank in use attempts will be made to extend the life of some tanks to cover a second chassis.

Mr Phillips pointed out that he considers efficient operational management of the fleet to be more important than vehicle selection, important though this is. His philosophy is that using the wrong vehicle results in operating costs marginally higher than they should be but if the right vehicle is wrongly operated then costs will be dramatically higher. In trying to establish this concept with the managers he said that they had had to strip away the traditional transport manager's view of operating and had returned to first principles. The company manages every vehicle as a business and has studied wayls of achieving improved utilization such as night work and even round-the-clock working.

Transport and distribution performance information and costs are collected and analysed at the Harlow Centre. A detailed budgetary system is in use — established by Mr Phillips annually in consultation with the commercial and sales people — and at set intervals operating performance is compared with the budget.

On costing Mr Phillips said that they had tried both sophisticated and not so sophisticated systems but the one in use at present provided all the information which could be obtained quickly enough to be of any value. This was not all the information they would like but Mr Phillips believes it important to have that information which can be reacted to very quickly.

Costs assessment Costs are assessed in detail down to a class of vehicle operating at a particular depot — not every vehicle individually. In the costing system the compan* is looking' for the basic criterion by which to assess performance and improvement of efficiency.

A great deal of paperwork is involved in trying to produce a detailed day-to-day analysis so the system adopted is to take a weekly survey which is sufficient within a few days to reveal trends of fall-off in vehicle or driver utilization and labour costs. These trend figures are computed to show trends over a period of a year.

Labour costs are high where bagged deliveries are necessary owing to the need for double manning in some instances. They can amount to 60 per cent of total cost compared with 35 per cent in the case of bulk deliveries. Labour costs are assessed on the basis of "per ton delivered" and "per vehicle mile" and if this figure increases it obviously indicates a drift in efficiency. One of the problems with the bagged delivery work is that if a second man is needed on the vehicle for one of the deliveries he then has to ride with the vehicle for the whole of the remainder of the journey when he is not needed. A cost comparison quoted by Mr Phillips showed that with two men on a vehicle delivering 8 tons in the day the labour cost per ton was £1.60 while with a bulk tanker it was possible to deliver 36 tons in a day at a labour cost of only 25p per ton. It proves the point made to me that with multiple bagged deliveries .labour cost is the critical element but with bulk work it is vehicle utilization which has to be watched.

Night driving Some 20/25 per cent of the tankers operate on two shifts of 10 hours each and this has resulted in a higher average level of vehicle earnings in a shorter time. There is, in some instances, resistance from the drivers to increased night working although those who do such work get a premium payment for it.

Driving staff play an important part in the operations, as they do in any transport organization, but with such highly specialist vehicles of very high capital value there is a particular need for B.I. Transport to take special care over selecting its tanker drivers. Most of these are men who have worked for the firm for many years and have graduated to these big vehicles from smaller ones. This provides a line of promotion and a means of relieving the older drivers from heavy bagging work. The company has its own driving instructors and is training, to a certain extent, for its future driver requirements because Mr Phillips is sure that in the future he will not be able to recruit suitable ready-made drivers from outside.

Although Transport is essentially independent of RHM in many ways — it was incorporated as a separate company in 1920 as the transport company of Joseph Rank Ltd — it is very much integrated with the RHM production process. For example, the RHM trend towards reducing production points, which it has done to some considerable extent in recent years, has a sharp upward effect on distribution costs both for the RHM fleet and for the B.I. Transport fleet but, Mr Phillips told me, the balance is carefully considered between the savings resulting from rationalization of production and the increased costs of delivery.

The company does its own buying and selling of vehicles — including private cars for other parts of the group — spares and other supplies and the accounting for this is done by B.I. Transport's own staff. Where, however, it is convenient and practical to do so common group services are used. The use of the group computer in processing wages is an example. In any other sphere where the group can offer services these too are used if by doing so an optimum arrangement is achieved.

Computer routeing I asked Mr Phillips about the use of the group computer for vehicle route planning. He confirmed that this had been looked into but for the present the company is continuing to do this work manually. Computer exercises undertaken by other firms have been examined and RHM has carried out some exercises itself. It was found that manual methods of vehicle routeing and work allocation are still economically acceptable. On the bulk delivery work such planning is relatively easy and with multiple deliveries close day-to-day consultation with the sales department ensures that the delivery planners are given the right situation to start with. By this it is meant that everybody concerned is clear as to the size of the pack required, the day on which delivery is required and the time of day. With such information the transport planner can schedule journeys accordingly.

Some journeys entail as many as 45 drops and Mr Phillips is convinced that computer scheduling does not offer a viable alternative at this stage. A great deal of responsibility in such cases must rest with the driver to decide his route and sequence of deliveries to achieve the best result; this is confirmed initially, of course, by the fact that he completes all the deliveries in his permitted working hours and later by cost statistics showing he did not cover an excessive mileage. Drivers are not given an automatic freedom but it remains a crucial question how much freedom they can be given if the company is to retain a fairly strict control over the performance of both the vehicle and driver. If a route is mapped out in detail with specific instructions to be followed, this the driver will inevitably do despite any delays or difficulties. Mr Phillips feels that the need is to achieve a balance between no route and no instructions and laid-down routes.

Another point on which I questioned Mr Phillips was vehicle appearance and livery. A two-year painting cycle is adopted and livery styles are changed as part of this cycle. The present livery is based on the concept of retaining the group identity on the tractive unit of bulkers, namely the letters RHM and an ear of corn symbol with product advertising on the sides and rear of the tank, namely "Hovis — make it your daily bread". This, Mr Phillips says, has greater impact on the public who recognize the product name rather than the fact that the vehicles are carrying RHM bulk flour, a fact which was previously displayed. In designing the livery the main object was to get a well balanced and pleasing appearance for the whole outfit. With the golden brown and white colouring this has undoubtedly been achieved.