Scania's new engines

Page 15

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

THE ADDITION of the two latest charge-cooled models to Scania's range gives it a total of 10 engine variants with maximum power outputs ranging from 120kW (1 6 3hp) to 3 0 9kW (420hp), derived from three basic power units with swept volumes of 11, 11 and 14 litres (two of these variants, the naturally aspirated DNB and DN11 are not available in the UK). TIM BLAKEMORE reports from Sweden.

The turbocharged and chargecooled 14 litre V8 with a maximum power rating of 309kW (420bhp) at 1,900rpm (net installed to the ISO 1585 standard, which differs only slightly from BSAU 141a) is designated DSC 14 01, while the chargecooled 11 litre engine, with a maximum power rating of 245kW (333bhp) is designated DSC 11 01.

The "C" in these engine type numbers denotes air-to-air charge-cooling, to distinguish it from the air-to-water type used on Scania's D5i8.

Why do it?

So why has the Swedish manufacturer not standardised on one type or the other? Scania's engineers consider the airto-air system to be "technically, preferable" — it reduces the temperature of the inlet charge by 100°C whereas the air-towater system can only manage a temperature reduction of 60°C — but they believe, probably quite rightly, that operators of the lighter 82 Series vehicles would be less willing to accept the extra cost and weight of the additional radiator and "plumbing" necessary for the air-to-air type.

Furthermore, the generous capacity of the eight litre engine's existing cooling system meant that no modifications had to be made to it when the conventional inlet manifold of the DS8 engine was replaced with the integral manifold/charge cooler of the D5i8.

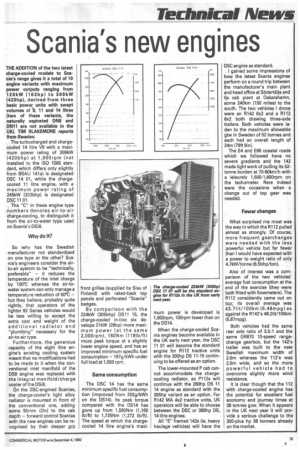

On the DSC-engined Scanias, the charge-cooler's light alloy radiator is mounted in front of the conventional one, adding some 50mm (2in) to the cab depth — forward control Scanias with the new engines can be recognised by their deeper grp front grilles (supplied by Sisu of Finland) with raked-back top panels and perforated "Scania" badges.

By comparison with the 224kW (305bhp) DS11 15, the charge-cooled in-line six develops 21kW (28hp) more maximum power (at the same 2,000rpm), 160Nm (118Ib/ft) more peak torque at a slightly lower engine speed, and has an improved minimum specific fuel consumption — 197g/kWh under full load at 1,550 rpm.

Same consumption The DSC 14 has the same minimum specific fuel consumption (improved from 202g/kWh on the DS14). Its peak torque compared with the DS14 has gone up from 1,580Nm (1,165 lb/ft) to 1,725Nm (1,272 lb/ft). The speed at which the chargecooled 14 litre engine's maxi mum power is developed is 1,900rpm, 100rpm lower than on the DS14.

When the charge-cooled Scania engines become available in the UK early next year, the DSC 11 01 will become the standard engine for R112 tractive units with the 305hp DS 11-15 continuing to be offered as an option.

The lower-mounted P cab cannot accommodate the chargecooling radiator, so P112s will continue with the 280hp DS 11 14 engine as standard with the 305hp variant as an option. For R142 MA 4x2 tractive units, UK operators will be able to choose between the DSC or 388hp DS, 14 litre engines.

All "E" framed 142s (ie, heavy haulage vehicles) will have the DSC engine as standard.

I gained some impressions of how the latest Scania engines perform on a round trip between the manufacturer's main plant and head office at Sodertalje and its cab plant at Oskarshamn, some 240km (150 miles) to the south. The two vehicles I drove were an R142 6x2 and a R112 6x2 both drawing three-axle trailers. Both vehicles were laden to the maximum allowable gtw in Sweden of 52 tonnes and each had an overall length of 24m (79ft 9in).

The E4 and E66 coastal roads which we followed have no severe gradients and the 142 made light work of pulling its 52tonne burden at 70-80km/h with a leisurely 1,500-1,600rpm on the tachometer. Rare indeed were the occasions when a change out of top gear was needed.

Fewer changes What surprised me most was the way in which the R112 pulled almost as strongly. Of course, more frequent gearchanges were needed with the less powerful vehicle but far fewer than I would have expected with a power to weight ratio of only 4.7kW/tonne (6.5bhp/ton).

Also of interest was a comparison of the two vehicles' average fuel consumption at the end of the exercise (they were both fitted with flowmeters). The R112 consistently came out on top; its overall average was 43.71it/100km (6.48mpg) as against the R142's 48.21it/100km (5.87mpg).

Both vehicles had the same rear axle ratio of 3.5:1 and the same GR870 10-speed rangechange gearbox, but the 142's trailer was built to the new Swedish maximum width of 2.6m whereas the 112's was 2.5m wide, and so the more powerful vehicle had to overcome slightly more wind resistance.

It is clear though that the 112 with charge-cooled engine has the potential for excellent fuel economy and journey times at 38 tonnes gcw. When it appears in the UK next year it will provide a serious challenge to the 300-plus hp 38 tonners already on the market.