THE COST OF REFUSE

Page 48

Page 49

Page 50

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

COLLECTION AND CLEANSING

Some Facts and Figures Relating to the Cost of Refuse Collection and Street Sweeping by Mechanized Vehicles andAppliances

THE interest of superintendents of refuse-collecting departments and of sanitary engineers is torn between the efficiency and cost of the operations involved. Normally, of course, the two go together, for cost is, generally speaking, a measure of the

efficiency of performance. In refuse collection and street cleansing, however, efficiency may be measured by the speed with which the refuse is removed and by the rapidity with which the streets are swept, garnished and made ready for traffic. In those circumstances it may happen that cost, whilst never, of course, a negligible factor, is, nevertheless one which must, perforce, be ignored to a certain extent.

There can be no doubt, however, that, other things being equal—that is to say, given the same quality and speed of performance—the departmental head who completes his task at least cost to that particular section of the community he serves, is clearly entitled to especial comenendathn. The fact that, if his costs seem high in comparison with C26

those of the rest of the country, he is liable to he taken to task, either directly or indirectly, by the Ministry of Health, is a further reason why those officials whose responsibility lies in the direction of refuse collection and street-cleansing will be interested in anything which indicates to them what those costs can, or should, be in certain circumstances.

In estimating or even assessing comparative costs of the municipal operations mentioned, the difficulty immediately encountered is that conditions ars rarely duplicated, so that comparisons become impossible.

Taking refuse collection first, the conditions may vary in two ways. They may differ in respect of the circumstances of collection, namely, the kind of refuse, and the arrangements of the houses and other establishments front which the collection has to be made, whilst they may differ also as to the methods of collection.

The Character of Refuse.

As to the former circumstance, an important point is the description of refuse, its composition and weight for bulk, From one district to another this factor may vary by as much as upwards of 100 per cent. In the smaller industrial towns of the North and Midlands, where all meals are taken at home, where coal fires are the rule, refuse consists mainly of vegetable matter and ashes. It is, consequently, heavy.

In other places, where most of the workers are away from home for the greater part of the time, the refuse is light in weight

Examples of heavy refuse are to be found in Lancashire, Yorkshire and the Midlands ; in Bury, Batley and Middlesbrough a weight of 7 cwt. per cubic yd. is customary. In Coventry, on the other hand, about 4 cwt. per cubic yd. is the average.,

This factor is of importance in endeavouring to arrive at a basis for assessing the cost. The speed of collection is more nearly determined in accordance with the number of bins collected per hour or per day, and as, in the majority of eases the bins are alike in size and are collected in about the same time, irrespective of weight, clearly it is unfair to assess the cost on the basis of weight collected. I say that notwithstanding the fact that the usual unit for Ministry of Health comparisons is the ton of refuse collected.

The Basis of Comparison.

A fairer basis of comparison is the number of houses dealt with in a given time. Most cleansing superintendents take the cost per 1,000 houses as the basis of comparison, and that appeals to me as being the more rational procedure.

There are thus clearly two factors in the cost of refuse collection. They are (a) the cost of lifting the bins and transferring them to the waiting vehicles and (b). the cost of operating the vehicles themselves.

In considering factor b, I come to the second set of variables in the problem, namely, the different methods of collection in vogue. Roughly speaking, there are two principal ways of collecting refuse ; there are more than a dozen in all, but by classifying them into these two groups the problem of costing is simplified.

In the one case the refuse is collected mid is at once taken in the vehicle to the dump or destructor, the collecting unit operating under its own power. In the other the refuse is collected, taken to some adjacent centre and then moved to the dump by means of another vehicle.

The deciding factor in making a choice of these two principal methods is the distance from the centre of the collecting area to the dump or destruc tor. If that distance be comparatively short, the former method is preferable, but if the way be long the latter is better and more economical.

Types of Vehicle Used.

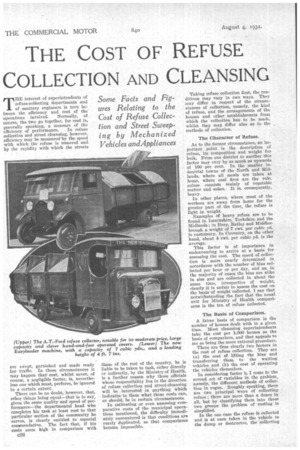

For the first method motor vehicles, either petrol-engined or electrically pro pelled, are generally used. For the other either small tractors are employed in conjunction with trailers or, as in the Pagefield method, horse-drawn collecting vehicles and a large motor vehicle transports the refuse to -the dump.

When tractors and trailers are used the trailers are generally horse-drawn while collection is made and tractordrawn to the dump. In another system the horse-drawn wagons, when full, are hauled on to the petrol lorry by means of a winch, and transported to the dump. Here the contents are dumped without removing the lorry from its carrier, after which the outfit travels back to the collecting area, where the empty lorry is exchanged for a full one.

There is one method which, whilst it is actually of the former class, has some of the characteristics of the latter. The vehicles employed are electrically driven, having two speeds, one giving 2 m.p.h. and the other 12 m.p.h. The low speed is in use while collection is taking place and the high speed employed for transport to the dump. This is quite a practical scheme if the organieation be such that there is always an empty vehicle on hand to replace a full one when that is ready to depart, so that the gang of loaders does not ever have to stand idle.

How Costs are Determined.

I have stated that there are two factors in determining costs, namely, the speed of collecting bins and the cost of operating the vehicles employed. The second of these is known; it may, with a fair degree of accuracy, be assumed to be that quoted in The Commercial Motor Tables of Operating Costs. The first is governed by the arrangement of the houses from which refuse is to be collected and the customary procedure in bin collection.

If the houses be close together, as in one of the older streets of poorer class of Louse, and if the residents bring the bins to the edge of the pavement to facilitate collection, all the conditions are present for facilitating collection as much as possible. If, on the other hand, the houses be widely spaced, set back from the road, and if the residents themselves do not bring out the bins, collection is much slower and the cost of collection is correspondingly greater.

It is these conditions—that the loaders and vehicles be kept continuously employed—and the need for the attainment of maximum efficiency which determine the speed of collection and the maximum distance to the•dump. In such cases the most economical procedure is to have two vehicles working together, with Complete gangs of loaders and a driver for each, the latter men to

work on either or both of the machines, as circumstances demand.

The men go out in . advance of the vehicles, so that they are ready to commence loading so soon as the latter

arrive. One of the Vehicles is loaded more quickly than the other by the simple expedient of diverting most of the loaders to that one, and it departs to the dump when full, leaving the other to be loaded by all the loaders and the one driver, working together. If the , scheme be properly worked out, the first lorry will have returned before the second one is loaded. • • It will readily be seen that the maximum distance to the dump is that which allows one lorry to make the double journey, with time to tip, and return, while the other is completely loaded.

For example, assume a vehicle of 7 cubic yd. capacity, that there are Eve men, including the driver, to each machine, and that the loading and col

lecting conditions are such that each man can collect and load between 10 bins cud 12 bins per hour. It will thus take nine of the men, all concentrating their efforts on the one vehicle, about an hour to load.

The distance to the dump, therefore, from that point of the area which is farthest away, must be such as will allow the loaded vehicle to travel to it, deliver its load, and return in an hour. If an average speed of 10 m.p.h. be assumed and 10 minutes be allowed for tipping the load, then that maximum distance is four miles. The average

length of haul, over the whole area to be collected, will thus be about 2i miles.

If the rate of bin collection be slower, or if vehicles of large capacity are employed, or speedier ones, then the foregoing figures must be altered accordingly.

Now to assess the cost of collection. Each vehicle will make four round journeys per day. As the average distance from the centre of collection to the dump is 2i miles, the total length per trip will average six miles, allowing a mile for collecting. The daily mileage will be 24, or, say, 150 per week, in round numbers.

The cost of operating a 2-tonner covering that mileage per week is £7 6s., or 114 12s. for the two vehicles. That figure includes,of course, the wages of the drivers. Add £23 4s. for wages of eight loaders at 58s. each per week. The total is £37 16s., for which sum approximately, 4,000 houses have been cleared of refuse. -Under those conditions the cost per 1,000 is £9 9s. Similar methods can be used to estimate the probable cost of refuse collection by the system described, under different conditions.

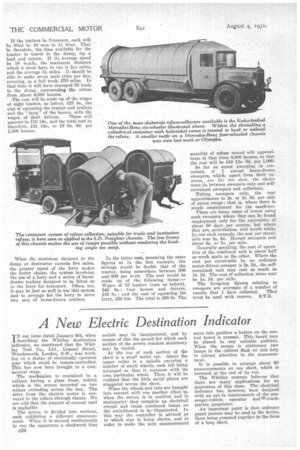

With tractors and trailers, assuming again that the organization of the work is such that trailers as well as loaders are continuously employed, three trailers are necessary successfully to carry on the work. The tractor can also be made to run practically continuously, so that it is alwaye either bringing an empty trailer back from the dump or taking a full one to it. If the trailers be 3-tonners, each will be filled by 10 men in 11 hour. That is, therefore, the time available for the tractor to travel to the dump, tip a load and return. If its average speed be 10 m.p.h., the maximum distance which it must have to run is five miles, and the average al miles. It should be able to make seven such trips per day, covering, in a full week, 270 miles. In that time it will have conveyed 38 loads to the dump, representing the refuse from about 4,500 houses.

The cost will be made up of the wages of eight loaders, as before, 123 4s., the cost of operating the tractor and trailers and the " keep " of the horses, with the wages of their drivers. These will amount tot18 14s., and the total cost is, therefore, 141 18s„ or £9 Os. 6d. per 1,000 houses.

When the maximum distance to the dump or destructor exceeds five miles, the greater speed of the lorry makes the better choice, the system involving the use of a lorry and a series of horsedrawn trailers designed to he lifted on to the lorry for transport. Often, too, it may be just as well to use this system and to arrange for the lorry to serve two sets of horse-drawn trailers.

In the latter case, assuming the same figures as in the last example, the mileage would be double that of the tractor, being somewhere between 500 and 600 per week. The cost would be made up of the following items:— Wages of 16 loaders (rate as before), £46 8s. ; four horses and drivers, £19 Ss.; and the cost of operating the lorry, £20 10s. The total is £96 6s. The quantity of refuse moved will approximate to that from 9,000 houses, so that the cost will be £10 12s. 6d. per 1,000.

So far as street sweeping is concerned, if I except horse-drawn sweepers, which, apart from their expense, are far too slow, the choice must lie between sweepers only and selfcontained sweepers and collectors.

Taking sweepers only, the cost approximates to 2s. or 2s. 6d. per mile of street swept ; that is, where there is ample employment for the machines.

There are many cases of towns using such sweepers where they can be found employment only for the equivalent of about 50 days per annum, but where they are, nevertheless, well worth while. In one such example, the cost per street. mile was 4s. 4d. Horsed sweepers cost about 6s. or 7s. per mile.

Generally speaking, the cost of operation of the combined unit is about half as much again as the other. Where the cost per street-mile by an ordinary motor-driven sweeper is 2s. 2d., the selfcontained unit may cost as much as 3s. 3d. The cost of collection alone may be 1s. 3d. per mile.

The foregoing figures relating to sweepers are averages of a number of results that I have collected. They must be used with reserve. S.T.R.