Emissions limits such as Euro - 1 and Euro - 2 are fine in

Page 34

Page 35

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

theory, but most trucks on UK roads are too old to be affected by them. If the Government really wants to reduce exhaust emissions, it needs to reward operators who clean up their existing vehicles.

A,

ccording to Department of Transport statistics 71.5% of Britain's ommercial vehicles over 35 tonnes gross are more than five years old and more than 10% are over 10 years old. Fewer than 30%—about 120,000—meet even the old Euro-1 emissions standard, let alone Euro-2. By 2010 emissions from new diesels will have been cut by 80% but with Euro-3 already on the horizon there is no doubt that legislators will continue to turn the screw.

The stream of EU and UK emissions regula tions may satisfy the electorate—if not the environmental lobby—but with an ageing lorry parc it will be years before they begin to bite. Progress towards cleaner air would be much quicker if there were incentives to clean up the exhausts of the 300,000 pre-Euro-1 diesels running on UK roads.

There are well established methods of cleaning up emissions on existing engines. They include exhaust filters; fuel additives; revised injection equipment (and possibly pistons); light supercharging; synthetic oils; and alternative fuels. But they all cost money, and in a fiercely competitive market few operators will be inclined to do more than the law requires.

Engineers in the Government departments of Transport and Environment are sympathetic to the merits of encouraging after-market treatment of ageing trucks, but that could leave hauliers arid enforcement agencies alike in a legal minefield. Set a design standard and, under existing legislation, the vehicle's emissions are more or less fixed for life—with good reason. If the law were changed to allow the modifications needed to reduce emissions who could guarantee that any given change would be safe, let alone effective?

However, one simple, cost-effective concession might be to type-approve specific components; and realistically that could only apply to exhaust purifiers.

There also seems to be scope for converting to alternative fuels such as liquified petroleum gas (propane), compressed natural gas (methane), or petrol. They depend to some extent on catalytic exhaust treatment to achieve their emission benefits, but emissions are routinely measured as part of the annual test.

Running on a different fuel, or a different grade of fuel, can be encouraged by tax concessions—this is already the case with unleaded petrol. But if it entailed pouring an additive into the fuel human error would have to be taken into account.

That factor contributed to the misgivings of London Buses about Lubrizol's exhaust filter which depends on a copper-solution additive in the fuel. This system, called the EZ trap, is the most durably effective diesel exhaust treatment—the copper deposits induce low-temperature oxidation of 75% of exhaust particles. But worries about whether garage staff would put too much additive into bunker tanks (or too little, or none at all) spoiled the practical appeal of the EL trap, says London Buses' principal engineer Simon Brown.

It's obviously more straightforward to simply replace a vehicle's silencer with an oxidising catalytic converter. Tests at Millbrook Proving Ground show that this can cut particulate emissions by 50%.

By coincidence that's the size of the grant which Swebus in Gothenburg receives from the Swedish government towards the cost of fitting Eminox exhaust systems incorporating Johnson Matthey catalysers. The effectiveness of this sort of cash incentive is being monitored by by other governments and by the European Commission, which has already stated its support for the principle of rewarding low-emission vehicles.

Even without government rewards, catalytic filters are interesting plenty of operators who value public approval; notably those running buses and municipal trucks.

The Johnson Matthey catalyser costs around £1,900-, Lubrizol subsidiary Engine Control Systems of Thatcham, Berks has entered the market with a catalytic converter called the AZ which can cost as little as £1,500, depending on engine size and the number ordered. Direct replacements for silencers are being sold by Fleetmaster Bus and Coach of Horsham, West Sussex.

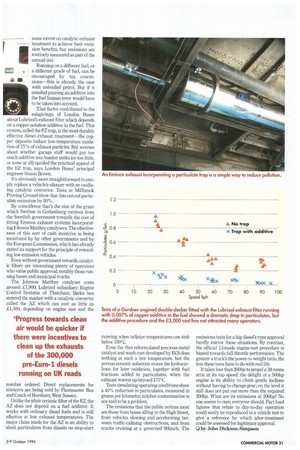

Unlike the plain ceramic filter of the EZ, the AZ does not depend on a fuel additive. It works with ordinary diesel fuels and is still effective at low exhaust temperatures. The major claim made for the AZ is an ability to slash particulates from diesels on stop-start running when tailpipe temperatures can sink below 150°C.

Even the thin reformulated precious-metal catalyst and wash coat developed by ECS does nothing at such a low temperature, but the porous ceramic substrate stores the hydrocarbons for later oxidation, together with fuel fractions added to particulates, when the exhaust warms up beyond 175°C.

Tests simulating operating conditions show a 40% reduction in particulates, measured in grams per kilometre; sulphur contamination is not said to be a problem.

The emissions that the public notices most are those from buses idling in the High Street from vehicles slowing and accelerating between traffic-calming obstructions, and from trucks cruising at a governed 90km/h. The emissions tests for a big diesel's type approval hardly mirror these situations. By contrast, the official 13-mode engine-test procedure is biased towards full-throttle performance. The greater a tuck's the power-to-weight ratio, the less these tests have to do with real life.

It takes less than 200hp to propel a 38-tonne artic at its top speed: the delight of a 500hp engine is its ability to climb gentle inclines without having to change gear; on the level it still does not put out more than the required 200hp. What are its emissions at 200hp? No one seems to care; everyone should. Part-load figures that relate to day-to-day operation could easily be reproduced in a vehicle test to give a reference by which after-treatment could be assessed for legitimate approval.

Ll by John Dickson-Simpson