Worker participation in action

Page 46

Page 47

Page 56

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

THE special risks of transport as a job, and the participation of employees in management, were examined in an Eastern European context by Professor Dr V. Kolaric of Belgrade University, Jugoslavia.

His paper provided a glimpse of the Jugoslavian variety of Communism at work and it was interesting to learn how worker-controlled State enterprises measured up to his statement that : "The problem of labour productivity is one of the most important in contemporary society."

In Jugoslavia, said Prof Kolaric, it was the workers who jointly managed transport undertakings, just as they did in other sectors of the economy. All management functions were performed by autonomous managing bodies of the shop-floor organisations in • the transport undertaking. The "labour organisation collectives "—the workforce—therefore assumed responsibility for all the economic consequences of the way the business was run.

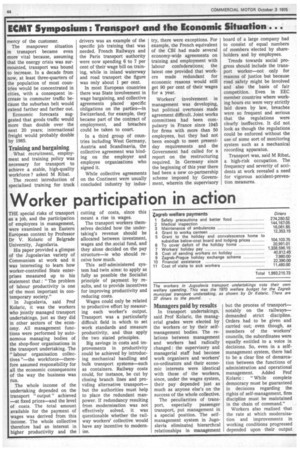

The whole income of the undertaking depended on the transport " output " achieved —at fixed prices—and the level of costs. The total amount available for the payment of wages was derived from this income. The whole collective therefore had an interest in higher productivity and the cutting of costs, since this meant a rise in wages.

The transport workers themselves decided how the undertaking's revenue should be allocated between investment, wages and the social fund, and they alone decided on the pay structure—ie who should receive how much.

This self-administered system had twin aims: to apply as fully as possible the Socialist principle of payment by results, and to provide incentives for improving productivity and reducing costs.

Wages could only be related to productive effort by measuring each worker's output. Transport was a particularly difficult field in which to set work standards and measure productivity, and thus apply the two stated principles.

Big savings in costs and improvements in productivity could be achieved by introducing mechanical handling and bulk transport systems—such as containers. Railway costs could, for instance, be cut by closing branch lines and providing alternative transport— but the authorities must help to place the redundant manpower. If redundancy resulting from modernisation was not effectively solved, it was questionable whether the railway workers' collective would have any incentive to modernise.

Managers paid by results

In transport undertakings, said Prof Kolaric, the managerial grades were elected by the workers or by their selfmanagement bodies. The relations between management and workers had radically changed : the supervisory and managerial staff had become work organisers and workers' co-ordinators and their economic interests were identical with those of the workers, since, under the wages system, their pay depended just as much as anyone else's on the success of the whole collective.

The peculiarities of transport, especially passenger transport, put management in a special position. The selfmanagement system in Jugoslavia eliminated hierarchcal relationships in management but the process of transport— notably on the railways— demanded strict discipline. Orders had to be given and carried out; even though, as members of the workers' councils, the subordinates were equally entitled to a voice in decisions. So, even in a selfmanagement system, there had to be a clear line of demarcation between the functions of administration and operational management. Added Prof Kolaric : "While complete democracy must be guaranteed in decisions regarding the rights of self-management, firm discipline must be maintained in the chain of command."

Workers also realised that the rate at which modernisation and improvements in working conditions progressed depended upon their output and their decisions on how revenue should be allocated. In more than a few cases, the workers' collectives had obtained the consent of their members to deducting part of their wages to go towards financing faster modernisation, improvements in technology and 'better working conditions.

Prof Kolaric said that, unlike most factory workers, transport people often suffered constant movement of their place of work and changes in the work/rest cycle. Shift work, changes of route or depot were common; shift work disturbed •the human biological rhythm, mealtimes and sleeping times were upset and there were often periods away from home when undesirable habits, such as drinking and gambling, were developed through boredom. In trucks and trains the crew were often subjected to prolonged noise and the higher its intensity and the lower its frequencies, the worse were its ill-effects.

Eating and drinking

Transport employees tended to eat hurried meals in relatively unhygienic conditions; the intake was mainly "dry," or food was brought from home and could easily go bad. Lorry and bus drivers generally bought their meals out, ate them hurriedly and were more likely to have alcohol with the meal than if they ate at home. All this was detrimental to health and the incidence of occupational complaints. The diet was lacking in fresh vegetables, with consequent vitamin deficiency, and few travelling staff in transport had regular access to fresh drinking water.

Drivers of vehicles were exposed to traffic fumes, and medical investigation had shown that petrol fumes had particularly serious effects on the sympathetic nervous system. Increased perspiration, low blood pressure and skin problems could ensue, while gastric juices were also disturbed. In confined cabs acrolein fumes could affect respiration, increase sleepiness and reduce mental concentration.

Transport workers in direct contact with customers (eg passengers) and loads were exposed to infection and there were obvious social and family problems connected with the way of life.

Transport workers had particular living and working conditions which distinguished them from all other types of employee, and these conditions did not depend solely upon the undertakings themselves. The economic and social working conditions of transport workers should not be the concern of transport undertakings and their management alone, but of the whole community including the State. The State, he said, must not only prescribe the right working conditions and enforce health, safety and welfare measures but must contribute towards a provision of transport workers' material living and working conditions.

In the discussions which followed the two papers, several Continental delegates complained of the poor deal which transport workers received, in providing a public service. Mr Bolado Hernandez, chairman of Valencia's transport undertaking, said his employees worked very long hours, got only one Sunday off in two months, and had to take their annual holidays in January and February. Drivers suffered circulation troubles from long sitting and the staff sickness absence in winter was 17 to 18 per cent.

Labour costs, at 72 per cent of gross revenue, had forced productivity changes and they now had only four employees per bus, compared with seven a few years ago. But what work could you offer a 45/50year-old driver whose driving days were over?

A Madrid Transport director regretted •the lack of statistics comparing the public transport productivity of big cities. In Madrid they had tried to establish an index of productivity and their researches showed that any improvement in service quality—which the public was demanding—meant an increase in labour content. And labour cost already took 70 per cent of revenue.

M. J. Landreville from the French transport users organisation, in Paris, said it was becoming increasingly difficult to recruit freight staff, too, for jobs with unsocial hours, notably freight handling. He wondered whether shippers might have to tailor their requirements to meet the availability of transport staff in future.

As reported in CM last week, the director-general of Britain's Road Passenger Transport Confederation, Mr Denis Quin, warned that if the industry lost sight of the fact that it existed to serve society, transport jobs as well as transport undertakings would be at risk.

The National Freight Corporation's vice-chairman, Mr Victor Paige, felt the adverse conditions of transport workers had been much overstated. Many workers were in transport by choice, and enjoyed its rewards. The haulage driver valued the freedom he would not find in a factory. It was a gross misrepresentation to base discussions on the assumption that transport working conditions were universally bad.

Mr H-H Binnenbruck of West Germany's BDG (road haulage association) felt that some of the problems stemmed from the fact that "demand transport" had greatly increased in recent years, compared with scheduled transport. But solutions could be found without invoking blanket intervention by the State—which was more effective in the very area of regular, scheduled transport.

M J. Vrebos, secretarygeneral of the Belgian Ministry of Communications, felt that too often the railways were simply running services to preserve jobs. Technology offered big cuts in the labour force. Countries were also being too nationalistic in the use of labour, -and missing many opportunities.

When the discussion turned to worker participation, Mr Paige warned that many managers, especially the autocratic type, had not yet realised how powerfully the demand for participation was a reflection of the social forces that were at work. We were going to see fundamental changes in management methods and management style, and in the training requirements of trades unions as a result.

After Mr Tavcar of Jugoslavian Railways had declared that railways would always remain " an instrument of national economic policy which could not be operated in response to market forces," Mr Paige said that if an industry did not match up to the market needs, society should ask whether it could afford to perpetuate overmanned and outdated undertakings. The stagecoach and the packhorse had gone; there had to be a dynamic for progress. If managements were efficient, concerned and compassionate, if trade unions were free and powerful, and if users were able to make their voice heard, then service levels did improve and the conditions of the transport employee similarly improved.

Fuel and space

The symposium heard conflicting views about shortages of fuel and land space, but on balance accepted that there was no call for crisis action.

In a paper on raw material resources and transport (see News pages in this issue) Professor Bayliss of Bath University suggested that in a time of fuel shortage, a combination of pricing and rationing would be the most effective way of channeling fuel into productive usage—a proposal aimed mainly at private motoring. He showed how, because service quality rather than price was such an important factor in much of freight movement, fuel price increases passed on to customers by hauliers would not themselves cause a big drop in traffic offered. This was not so true, however, of the railways.

A Dutch Ministry of Transport delegate revealed that if everyone in Holland had used their fuel coupons during the 1973 crisis, the country would have consumed more fuel than during a non-rationing period. He and other speakers were sceptical of rationing as an effective tool.

A Danish delegate gave figures to show how the forecast effects of a 50 per cent fuel price increase had been proved utterly wrong. Car usage had dropped only marginally—not massively as forecast—and public transport patronage had risen by only 1 per cent.

Mr E. H. M. Price, the DoE's director of economics, thought motorists would not switch significantly to public transport while present standards of frequency and comfort prevailed.

Professor Sir Colin Buchanan (who chaired one of the sessions) thought the motivation for individual journeys was not well researched. Many were the result of spur-of-themoment decisions for which the availability of personal transport was crucial. They did not fit 'into a regulated pattern, and any attempt to force them from private to public transport would lead to journeys being " lost " rather than transferred.

The problems of this "trip suppression" were also mentioned by Dr D. A. Quarmby of London Transport Executive. Not enough was known about the number of individual journeys which were " suppressed " by price or rationing, or which were transferred to public transport. In December 1973 LTE had made a survey in its operating area, asking motorists what they would do if rationing limited them to 50 miles a week. The answers showed that one-third of car trips would be switched to public transport, one-third to some car-sharing arrangement and one-third would be suppressed.

A paper by M. P. Hatry, of Brussels University, and statements by other delegates, emphasised the much more productive use of fuel achieved by public than by private transport. But the general conclusion of the symposium seemed to be that there was very limited scope for fuelsaving by mode-switching (eg car to bus) even if this could be achieved. There was greater scope for global fuel savings by technical improvements— for example, more economical car engines—and there was some debate about whether or not governments should set standards for this. It was pointed out that the US Government had given manufacturers strict mpg targets for 1980 vehicles.

Mr M. D. Bayliss, the GLC's chief transportation planner, told delegates he thought the transport use of land had been overstated. In London only 11 per cent of the land was used for transport, and only 11/4 per cent for through-transport. Eliminating wheeled • traffic would release very little land for other uses in urban areas, He asserted that in terms of land use, the railways were only one-tenth as efficient as road transport in carrying urban freight.

Symposium papers:

Human Factors and Transport : papers by J. Ribat, chief of land transport service and employment, French Ministry of Transport; and by V. Kolaric, University of Belgrade.

Raw Material Resources and Transport : papers by B. Bayliss, director, Centre for European Industrial Studies, University of Bath; and by P. Hatry, University of Brussels. Land-use Resources and Transport: papers by J. Hernando, secretarygeneral, land transport, Spanish Ministry of Public Works; and by G. W. Heinze, Berlin Technics! University.