CARRYING CONTROVERSY

Page 35

Page 36

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Few truck operations polarise opinion as much as the transportation of nuclear fuel and waste. Tony Cox, of British Nuclear Fuels' Springfields works, is responsible for the safe carriage of these controversial goods.

• For many the very thought of carrying nuclear waste by road conjures up nightmares of an apocalyptic accident on a foggy motorway; fission in the fast lane.

Others believe we have sufficient controls in this country for nuclear fuel and waste to be transported by road safely. For them road transport presents the most reliable and cost-effective way of moving nuclear products.

This is certainly the view of Tony Cox, transport manager at British Nuclear Fuels' Springfields works near Preston. Springfields produces several thousand tonnes of nuclear fuel each year both for export and for use in Britain's 26 nuclear power stations.

"At BNFL we place the utmost importance on the safe movement of our product," says Cox. Virtually all of the fuel produced at Springfields is transported by road, whether to other UK nuclear installations or to ports from which it is transported around the world.

Over the years the greater reliability of road transport has speeded the move away from the railways. Safety aside, reliability is an important consideration for BNFL because each truck-load of nuclear fuel is worth around £1.5 million and Springfields is only invoiced on delivery. Cox runs a fleet of 60 vehicles, about half of which are site vehicles, such as staff buses and stores trucks used at Springfields. Most of the remaining vehicles are 38-tonne tractive units used to transport nuclear fuel and waste around the country, to the ports and overseas.

All movements of nuclear products by road in this country are governed by The Radioactive Substances (Carriage by Road) (Great Britain) Regulations of 1974. The regulations state: what documentation has to be carried in the vehicle; what sort of protection needs to be afforded to the driver; what procedures need to be followed by the operator and driver; and what should be done in an emergency.

When a driver takes a radioactive load on the road he or she first has to report to a radioactive movements office (there is one at every nuclear installation in the UK) for a consignor's certificate.

RADIOACTIVITY

The driver must also ensure that the truck is monitored for radioactivity. No BNFL vehicles are allowed onto the roads if radioactivity levels exceed prescribed limits, and all vehicles undergo a fourminute test before leaving the site. If a vehicle is found to exceed the radiation limits it will be thoroughly cleaned until it passes the test. Every clean vehicle is issued with a radiation certificate confirming that radiation levels within the driver's cab are at a safe level. The driver also wears a blue film badge which records his personal exposure to radiation.

Department of Transport officials regularly stop BNFL trucks to check their radiation levels and if these exceed the prescribed limits a major call-out scheme is invoked under the National Arrangements for Incidents Involving Radioactivity (NAIR) scheme. Similarly, if there is an accident or spillage involving nuclear products on the roads, NAIR will be invoked.

Each BNFL vehicle carries two fire extinguishers and a special blue barrel which contains a tool kit for emergency repairs, two flashing amber lights, a warning triangle and a box of bulbs, fuses and insulation tape; all required under the regulations. The driver must also ensure that the vehicle displays the correct radioactive load placards, including a metal fireproof one which must be conspicuously display ed inside the driver's cab.

Drivers are expected to stay with their vehicles as much as possible. They are not allowed to take hitch-hikers or leave their vehicles out of sight. Neither are they allowed to unhitch the trailer from the tractive unit when off site.

Of course, different regulations apply in other countries so when transporting on the Continent BNFL vehicles have to conform to overseas regulations, including the International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Road (ADR) agreement.

BNFL expects its drivers to familiarise themselves with the regulations as they apply to each country. "We see it as his responsibility to ensure his vehicle conforms", says Cox. "It will be him who will be fined for any breach in the law."

Cox claims that he receives 20 applicants for every driving job and admits this is partly due to good pay rates. Each BNFL driver is put through a long training process to ensure that he or she understands the particular problems of transporting nuclear loads. First there is a week-long course, including one day's training at Sel!afield on fires on loads; two days on vehicle labelling and regulations; and three days on the road in the UK with an existing driver.

In the second week the trainee driver will travel abroad with an experienced driver. It will take a further three months before he is accepted as a fully-fledged BNFL driver.

None of the 25 Springfields drivers are allocated to particular vehicles. Under the payment scheme agreed with the Transport and General Workers Union, the drivers are paid different rates on different routes, so the routes are shared.

OUTSIDE HAULIERS

Although BNFL drivers are used on 90% of overseas consignments, Cox admits: "It is an impossibility to use our own drivers all the time. We can meet peak demand by using outside hauliers."

The outside contractors are vetted by the security services at the Springfields plant before they are given any work, and all the contractors' drivers are given a day's tuition on the regulations.

All of the 30 road-going vehicles in the Springfields fleet are Seddon Atkinsons. "We started with Seddon Atkinsons in 1983," says Cox. "We decided we needed to standardise because we were starting to go into Europe. We send perhaps eight abroad each week and we have never had a breakdown, even though the fleet covers around 1,200,000km (750,000 miles) each year."

All the tractive units are plated to 38 tonnes, though Cox estimates only half the journeys involve movements over 32 tonnes. "We were one of the first operators to upgrade to 38 tonnes," he claims, "because it allowed us to carry an extra cylinder. If we go to 40 tonnes in this country that would help us because it would allow us to carry two 14-tonne cylinders, which could virtually halve our transport costs.

"We've done plenty of research with aluminium chassis to try to engineer the vehicles to carry two cylinders at 38 tonnes, but we simply can't do it."

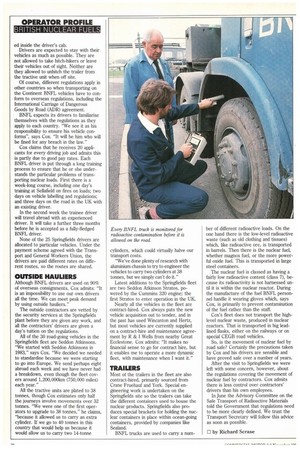

Latest additions to the Springfields fleet are two Seddon Atkinson Stratos, powered by the Cummins 320 engine; the first Stratos to enter operation in the UK.

Nearly all the vehicles in the fleet are contract-hired. Cox always puts the new vehicle acquisition out to tender, and in the past has used Wincanton and Hertz, but most vehicles are currently supplied on a contract-hire and maintenance agreement by R & 1 Wells from nearby Great Ecclestone. Cox admits: "It makes no financial sense to go for contract hire, but it enables me to operate a more dynamic fleet, with maintenance when I want it."

TRAILERS

Most of the trailers in the fleet are also contract-hired, primarily sourced from Crane Fruehauf and York, Special engineering work is undertaken on the Springfields site so the trailers can take the different containers used to house the nuclear products. Springfields also produces special brackets for holding the nuclear containers in place within ocean-going containers, provided by companies like Sealand.

BNFL trucks are used to carry a num

ber of different radioactive loads. On the one hand there is the low-level radioactive waste (such as old clothing and tissues) which, like radioactive ore, is transported in barrels. Then there is the nuclear fuel, whether magnox fuel, or the more powerful oxide fuel. This is transported in large steel containers.

The nuclear fuel is classed as having a fairly low radioactive content (class 7), because its radioactivity is not harnessed until it is within the nuclear reactor. During the manufacture of the fuel BNFL personnel handle it wearing gloves which, says Cox, is primarily to prevent contamination of the fuel rather than the staff.

Cox's fleet does not transport the highlevel nuclear waste, produced in nuclear reactors. That is transported in big leadlined flasks, either on the railways or on special CEGB road vehicles.

So, is the movement of nuclear fuel by road safe? Certainly the precautions taken by Cox and his drivers are sensible and have proved safe over a number of years.

After the visit to Springfields we were left with some concern, however, about the regulations covering the movement of nuclear fuel by contractors. Cox admits there is less control over contractors' drivers than his own employees.

In June the Advisory Committee on the Safe Transport of Radioactive Materials told the Government that regulations need to be more clearly defined. We trust the Transport Secretary will follow this advice as soon as possible.

0 by Richard Scrase