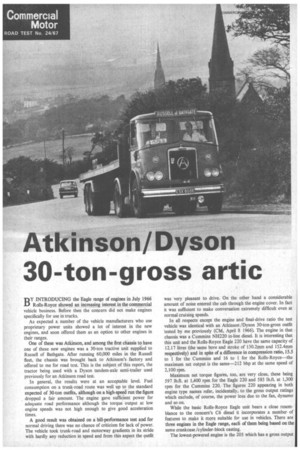

Atkinson/Dyson 30-ton-gross artic

Page 68

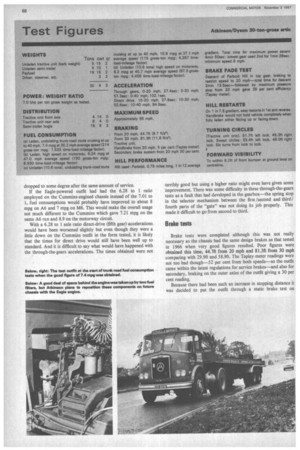

Page 69

Page 70

Page 71

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By

A. J. P. Wilding, AMIMechE, MIRTE DY INTRODUCING the Eagle range of engines in July 1966 Rolls-Royce showed an increasing interest in the commercial vehicle business. Before then the concern did not make engines specifically for use in trucks.

As expected a number of the vehicle manufacturers who use proprietary power units showed a lot of interest in the new engines, and soon offered them as an option to other engines in their ranges.

One of these was Atkinson, and among the first chassis to have one of these new engines was a 30-ton tractive unit supplied to Russell of Bathgate. After running 60,000 miles in the Russell fleet, the chassis was brought back to Atkinson's factory and offered to me for road test. This is the subject of this report, the tractor being used with a Dyson tandem-axle semi-trailer used previously for an Atkinson road test.

In general, the results were at an acceptable level. Fuel consumption on a trunk-road route was well up to the standard expected of 30-ton outfits, although on a high-speed run the figure dropped a fair amount. The engine gave sufficient power for adequate road performance although the torque output at low engine speeds was not high enough to give good acceleration times.

A good result was obtained on a hilt-performance test and for normal driving there was no chance of criticism for lack of power. The vehicle took trunk-road and motorway gradients in its stride with hardly any reduction in speed and from this aspect the outfit was very pleasant to drive. On the other hand a considerable amount of noise entered the cab through the engine cover. In fact it was sufficient to make conversation extremely difficult even at normal cruising speeds.

In all respects except the engine and final-drive ratio the test vehicle was identical with an Atkinson/Dyson 30-ton-gross outfit tested by me previously (CM, April 8 1966). The engine in that chassis was a Cummins NH220 in-line diesel. It is interesting that this unit and the Rolls-Royce Eagle 220 have the same capacity of 12.17 litres (the same bore and stroke of 130.2mm and 152.4mm respectively) and in spite of a difference in compression ratio, 15.5 to 1 for the Cummins and 16 to 1 for the Rolls-Royce—the maximum net output is the same-212 bhp at the same speed of 2,100 rpm.

Maximum net torque figures, too, are very close, these being 597 lb.ft. at 1,400 rpm for the Eagle 220 and 585 lb.ft. at 1,300 rpm for the Cummins 220. The figures 220 appearing in both engine type names refer, incidentally, to the gross output ratings which exclude, of course, the power loss due to the fan, dynamo and so on.

While the basic Rolls-Royce Eagle unit bears a close resemblance to the concern's C6 diesel it incorporates a number of features to make it more suitable for use in vehicles. There are three engines in the Eagle range, each of them being based on the same crankcase /cylinder-block casting.

The lowest-powered engine is the 205 which has a gross output of 205 bhp and a turbocharged version gives 260 bhp gross.

All three engines have the same bore and stroke dimensions and wet liners are used. To get the higher output on the 220 relative to the 205 the former unit has a different fuel-input level, and to match this larger inlet and exhaust valves.

The Eagle engine is around the physical size one would expect of a diesel with this output and it takes up a similar amount of space in the Atkinson chassis to that of the Cummins. Twin fuel filters are hung from a bracket at the rear of the block and these take up extra space to the rear of the cab; I was told that it is planned to reposition the filters soon.

The Rolls-Royce engine is mounted in the Atkinson T3246 as a unit with the gearbox and as with other layouts on this model,the rear supports are carried in a robust bridging cross-member over the gearbox.

The test chassis had a ZF six-speed overdrive unit which was found to be reasonably well matched to the characteristics of the Eagle although the spacing between fourth and fifth was wider than the ideal.

Improved braking system

Braking on the Atkinson tractive unit has now been superseded by an improved system announced in COMMERCIAL MOTOR last week. But the main change is in the parking brake. Instead of a multi-pull operating mechanism and mechanical linkage, the latest design has lock-type actuators on both axles. The same sizes and types of brake unit are used but with lock actuators at all four wheels the parking ability is potentially much greater.

The Dyson semi-trailer used for tests was a standard Newloader with 32ft 6in. long platform. As can be seen from the test-results table a load of just over 19.75 tons was carried and this brought the gross weight to a little over the 30-ton limit with the load placed on the semi-trailer body to give a good distribution over the four axles of the outfit.

First tests carried out were of fuel consumption over a 16.6-mile out-and-return journey on M6 north of Preston. In fact, two runs were made because of doubts about the accuracy of the figure for the first test. It turned out that this was correct and that the error was in calculation of the consumption figure from the fuel used. Road works on the circuit caused some hold up and introduced an intermediate stop which could have had a slight adverse effect on the result but even so the figure was good for a 30-ton outfit.

High-speed fuel consumption was checked in two stages while going to and from the test hill. The two sections made up a round trip between A6 Bamber Bridge and B5239 junctions, a total distance of 16.1 miles.

For most of the time on the motorway the Eagle engine was on the governor with the road speed at between 50 and 56 mph (the maximum on "run Out") and the only real drop in speed occurred on the gradient near the service area on this stretch when fifth gear was necessary for the final portion 4nd the speed was 42 mph. This was a very good performance but the consumption drop to 6.24 mpg was more than expected and a lot more than had been tile case with the Cummins-engined vehicle.

But the difference in axle ratio means that it is not possible to ompare directly the results from the two tests. And in any case :he saying that comparisons are odious applies as much to ommercial vehicles as it does to anything else. The Eagle had lone 60,000 miles while the Cummins was a brand new engine at he time of its test and it is likely that consumption would have

dropped to some degree after the same amount of service.

If the Eagle-powered outfit had had the 6.28 to 1 ratio; employed on the Cummins-engined chassis instead of the 7.01 to 1, fuel consumptions would probably have improved to about 8 mpg on A6 and 7 mpg on M6. This would make the overall usage not much different to the Cummins which gave 7.21 mpg on the same A6 run and 8.9 on the motorway circuit.

With a 6.28 to 1 axle ratio direct-drive (fifth gear) accelerations, would have been worsened slightly but even though they were a little down on the Cummins outfit in the form tested, it is likely that the times for direct drive would still have been well up to standard. And it is difficult to say what would have happened with the through-the-gears accelerations. The times obtained were not terribly good but using a higher ratio might even have given some improvement. There was some difficulty in these through-the-gears tests as a fault that had developed in the gearbox—the spring stop in the selector mechanism between the first /second and third/ fourth parts of the "gate" was not doing its job properly. This made it difficult to go from second to third.

Brake tests

Brake tests were completed although this was not really necessary as the chassis had the same design brakes as that tested in 1966 when very good figures resulted. Poor figures were obtained this time, 44.7ft from 20 mph and 81.3ft from 30 mph comparing with 29.9ft and 58.9ft. The Tapley-meter readings were not too bad though-52 per cent from both speeds—so the outfit came within the latest regulations for service brakes—and also for secondary, braking on the outer axles of the outfit giving a 30 per cent reading.

Because there had been such an increase in stopping distance it was decided to put the outfit through a static brake test on equipment installed at Atkinson's new Barnber Bridge service depot.. Here the fault was shown up very quickly and it was apparent that the 'offside front and offside trailer axles were not doing anything like their fair share of work.

Change of lining?

If each brake had been working as well as the best on the particular axle the indication would have been an efficiency of 51 per cent. As it was the figures suggested 44 per cent for the service brake. The readings from the driving axle brakes while being the same for both sides were lower than the front axle. The figures lead to the conclusion that a change of lining had been made in the vehicle's life and that those on the vehicle were not the high-coefficient type recommended by Atkinson. There was no time to check this before the vehicle went back into service.

The need for attention to the brakes was confirmed on the hill checks on Parbold Hill. Even with the maximum effort applied to the handbrake lever with the footbrake applied at the same time I could not induce the driving-axle brakes to hold the laden outfit facing up or facing down the 1 in 7.5 slope. Here again this is of rather historical interest with the changes that Atkinson has made in brake design.

In all other respects the Atkinson performed very well on Parbotd Hill. The time taken for a maximum-power climb was commendably short and restarts on the maximum gradient were easy in first when facing up the slope and in reverse when facing down.

During the test day the maximum speeds in the gears were checked and found to be 6, 10, 15, 25, 40 and 56 mph. these figures taking into account a speedometer inaccuracy which varied between four per cent fast at 30 mph and 10 per cent fast at 60 mph (indicator). This degree of inaccuracy is greater than is usual on test vehicles. It could also explain why the fuel consumptions obtained were less than the 8 mpg which Russells of Bathgate were said to have been getting. If it is accepted that the distance recorder was only five per cent optimistic on average during its 60,000 mile life—the actual reading will vary with tyre wear—it will bring this figure down to 7.5 mpg over a true distance; this is not much different to my figures which are based on accuratelymeasured distances.

Cab noise

The main thing that one could criticize about the test vehicle was the noise in the cab. As already pointed out this made conversation difficult. But the steering was heavier than I can recall from the first test referred to; some grease may have been needed.

Neither were the mirrors as good as on the earlier test and I found it impossible to set them to give a good view to the rear without having to turn my head excessively in order to use them. The mirror brackets were the cause of the trouble, those on the 1966 test vehicle being much superior in this respect.

Comments about the cab are largely superfluous as Atkinson has also made changes here in its standard design. Similar remarks as on previous Atkinson tests apply; access is reasonable, heating and demisting equipment adequate as also. is all round visibility. And accessibility to the engine is as one would expect with a fixed cab.