Construction and Use Regulations on lifting axles come into force

Page 54

Page 56

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

in January 1991. But if the Government gets its way, operators could be banned from using load transfer devices on trucks with high unladen weights.

• As reported in Commercial Motor (2531 January), road transport legislators in the UK have finally acknowledged the existence of load-transfer devices and lifting axles. The Department of Transport proposes to restrict their use, in transferring load from one axle to another, to assist traction, reduce part-laden tyre scrub wear or enhance part-laden ride. The Dip's concern centres on the possibility of individual axle loads exceeding the legal 10.5-tonne maximum.

Because some axles lift clear of the ground, effectively transforming a sixwheeled chassis into a four-wheeler, the DTp wants to clarify its definitions of wheelbase and overhang. This can be critical — mainly on tag-axle multi-wheelers — in the context of the long-standing regulation restricting rear overhang to no more than 60% of wheelbase. This is an understandable safeguard against rearward-biased weight distribution and excessive tail-end swing-out on corners. Some pundits say this is ironic, coming hard on the heels of the 16.5-metre artic legislation, which has the effect of greatly increasing semi-trailer overhangs.

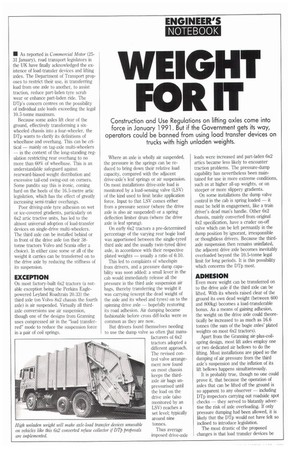

Poor driving-axle tyre adhesion on wet or ice-covered gradients, particularly on 6x2 artic tractive units, has led to the almost universal adoption of load-transfer devices on single-drive multi-wheelers. The third axle can be installed behind or in front of the drive axle (on their 38tonne tractors Volvo and Scania offer a choice). In either case some or all of the weight it carries can be transferred on to the drive axle by reducing the stiffness of its suspension.

EXCEPTION

On most factory-built 6x2 tractors (a notable exception being the Perkins Eaglepowered Leyland Roadtrain 20.33) the third axle (on Volvo 8x2 chassis the fourth axle) is air suspended. Virtually all thirdaxle conversions use air suspension, though one of the designs from Granning uses compressed air in the "load transferred" mode to reduce the suspension force in a pair of coil springs. Where an axle is wholly air suspended, the pressure in the springs can be reduced to bring down their relative load capacity, compared with the adjacent drive-axle's leaf springs or air suspension. On most installations drive-axle load is monitored by a load-sensing valve (LSV) of the kind used to limit brake application force. Input to that LSV comes either from a pressure sensor (where the drive axle is also air suspended) or a spring deflection limiter drum (where the drive axle is leaf sprung).

On early 6x2 tractors a pre-determined percentage of the varying rear bogie load was apportioned between the single-tyred third axle and the usually twin-tyred drive axle, in accordance with their respective plated weights — usually a ratio of 6:10.

This led to complaints of wheelspin from drivers, and a pressure dump capability was soon added: a small lever in the cab would immediately release all the pressure in the third axle suspension air bags, thereby transferring the weight it was carrying (except the dead weight of the axle and its wheel and tyres) on to the spinning drive axle — hopefully restoring its road adhesion. Air dumping became fashionable before cross diff-locks were as common as they are now.

But drivers found themselves needing to use the dump valve so often that manufacturers of 6x2 tractors adopted a different approach. The revised control valve arrangement now found on most chassis keeps the thirdaxle air bags unpressurised until the load on the drive axle (also monitored by an LSV) reaches a set level; typically around nine tonnes.

Thus average imposed drive-axle loads were increased and part-laden 6x2 artics became less likely to encounter traction problems. The pressure-dump capability has nevertheless been maintained for use in more extreme conditions, such as at higher all-up weights, or on steeper or more slippery gradients.

On some installations the dump valve control in the cab is spring loaded — it must be held in engagement, like a train driver's dead man's handle. Other 6x2 chassis, mainly converted from original 4x2 specification, have a cruder on-off valve which can be left permantly in the dump position by ignorant, irresponsible or thoughtless drivers. Because the thirdaxle suspension then remains uninflated, the adjacent drive axle becomes inevitably overloaded beyond the 10.5-tonne legal limit for long periods. It is this possibility which concerns the DTp most.

ADHESION

Even more weight can be transferred on to the drive axle if the third axle can be lifted. With its wheels raised clear of the ground its own dead weight (between 600 and 800kg) becomes a load-transferable bonus. As a means of gaining adhesion, the weight on the drive axle could theoretically be increased to as much as 16.6 tonnes (the sum of the bogie axles' plated weights on most 6x2 tractors).

Apart from the Granning air-plus-coilspring design, most lift axles employ one or two dedicated air bellows to do the lifting. Most installations are piped so the dumping of air pressure from the third axle's suspension and the inflation of its lift bellows happens simultanteously.

It is probably true, though no one could prove it, that because the operation of axles that can be lifted off the ground is so apparent to any observer — including DTp inspectors carrying out roadside spot checks — they served to blatantly advertise the risk of axle overloading. If only pressure dumping had been allowed, it is likely that the DTp would not have felt so inclined to introduce legislation.

The most drastic of the proposed changes is that load transfer devices be rendered inoperative where the drive axle is carrying more than 60% of its plated weight (6.3 tonnes on a 10.5-tonne axle).

A simple calculation shows that the DTp engineers want to prevent drive axle loads exceeding 10.5 tonnes, even for the briefest moment under conditions of incipient wheelspin. If implemented, it would mean that a 38-tonne plated/6x2-hauled artic laden to more than about 28 or 30 tonnes gross would have no recourse to load transfer traction assistance.

WINTER-TIME

Winter-time traction problems are by no means confined to partially laden trucks. Many 3 + 2 and 3 + 3 outfits laden up to 38 tonnes experience problems, particularly on gradients of 10% or more on Britain's older trunk roads.

Harmonised EC legislation, incorporating the DTp's new-load transfer axle proposals, would therefore be far less prejudicial to Continental than to UK operations. The fact that, until 1999, our individual axle weight limit is to remain at 10.5 tonnes — though most of our EC partners have had an 11-tonne limit since July 1988 — serves to further underline the "traction handicap" besetting British operators.

In its Construction and Use Regulation "retractable axle" amendment document, the DTp talks of prohibiting pressure dumping and axle-lift controls from the driver's cab. However, "certain exceptions" are immediately cited, whose subsequent definition covers any traction aid.

Despite the safeguard, in the shape of the 60% proposal against plated drive axle weights being exceeded, the legislators intend to impose a time limit of 90 seconds on each application of a load-transfer de vice. What's more, they say the pressuredump/axle-lift apparatus may not be used again until another 60 seconds has elapsed. A spring-loaded control requiring the driver to keep his hand on the lever will not be an acceptable alternative.

Automatic operation of axle loadtransfer equipment, when increasing or decreasing drive-axle loads reach pre-set levels, is implicitly encouraged by the Dip's proposals. But a requirement for a manual-override control, positioned outside the cab "and out of the reach of its occupants", is included, "for brake testing purposes".

Ambiguity as to the definition of overhang is removed in the same set of DTp proposals. Any sixor eight-wheeler with an axle that can be lifted clear of the ground is to be regarded at all times as if that axle was in contact with the road, when wheelbase and overhang are being determined.

Manufacturers, converters and other interested parties have been invited by the DTp to comment on the proposals. Some of them also gave their views to Commercial Motor.

John Davies of third-axle conversion specialist Phoenix Truck and Trailer Equipment was the exception in broadly welcoming the move. It would, he said, help reduce brake problems by evening out axle loads. The Italian self-tracking axles on the Weweler air suspension fitted by Phoenix did not need to be lifted for tyre-scrub or turning circle reasons. A time switch costing £86 could be fitted without difficulty to meet the 90secs/ 60sec requirement. Dave Scott of Grarming-Stemfast, and Chris Drinkwater of Southworth Engineering, had greater reservations. Scott said Granning would urge the the Dip to raise the 60%-of-plated drive-axle load limit (above which load transfer would be prohibited) to 80%. He pointed out that the drive axles on some specialist 6x2s, notably Granning-converted refuse collectors, carry well over half their plated weight in the unladen state.

Automatic inflation and dump call for an additional pressure sensitive control box and related solenoid pilot valve, said Scott, though they are well-proven items. He criticised the manual override demanded by the DTp outside the cab as being vulnerable to tampering.

FATAL EFFECT

In a letter to the DTp, Drinkwater says the proposals, if introduced unchanged, would have a profound, if not fatal effect on the nature and development of Southworth's business. He regrets that consideration of typical operating requirements appears to have been ignored by the DTp on the assumption (which he disputes) that the only benefit of a lifting axle to an operator is to reduce vehicle excise duty. The real benefits of a lift axle, he asserts, are: to provide a means of operating at weights between 17 and 24 tonnes without the cost and weight penalty of doubledrive; and, when partially laden, to reduce tyre and road wear through reduced scrub and suspension bounce.

Whether the DTp will get its way remains to be seen, but if the feedback generated so far is anything to go by, it may yet revise its plans.

0 By Alan Bunting