THE LOGICAL TRAILER

Page 106

Page 107

Page 109

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

ECONOMICS OF

HAULAGE

Hill Road Traffic Act, 1030, cou

T

siderably altered the conditions of ie

trailer use in this country. ',1-' 15

Before it came into operation trailers

T

z were chiefly% regarded as adjuncts to r. steam wagons and for use on short

distance haulage behind smaller types : 14

of industrial tractor. Now they are 8 being more and more used, for medium u and long-distance haulage in connection z o • with steam wagons, petrol and corni= a

<

multi-wheeled vehicles. Further in

crease in the use of trailers is more-'-' 12 1

conjunction with specially designed o .. pression-ignition-cngined lorries, also in te .....

o than likely, as users come more and more to to app%•eciate the opportunities for economy which they afford and as the heavier types of oil-enened chassis become more numerous.

A brief outline of the legal position of the trailer is an essential preliminary to discussing the economic pros and cons of its use. A trailer may be drawn by any type of mechanically propelled vehicle except (in the near future) a motorcycle. Those types comprise heavy locomotives, light locomotives, tractors, heavy motorcars and motorcars. All are permitted to haul trailers, the last two after payment of additional taxation. In this article I am concerned chiefly with the use of trailers in conjunction with heavy motorcars, motorcars and tractors.

A motorcar is a mechanically propelled vehicle the unladen weight of which does not exceed 21i tons. (There are certain exceptions to this which are not relevant to the present discussion.) A heavy motorcar having four wheels may weigh unladen as much as 7i tons, if it has six wheels it may weigh 10 tons, and if more than six wheels 11 A tractor, which is a motor unit that does not carry a load, may draw two empty trailers, but only one full one.

The maxicamn legal speed of a heavy motorcar or motorcar drawing a trailer i:: 1t: m.p.h., provided that both are equipped with pneumatic tyres : if on solid tyres the maximum speed is 8 m.p.h. The maximum speed of a motor tractor when drawing a trailer is 8 m.p.h. There is no provision in the Act for any extra speed allowance in case of a tractor and trailer on pneumatic tyres.

Whenever a tractot, heavy motorcar or motorcar is drawing a trailer, an extra man, additional to the driver, must be carried. There is an exception to this in the case of a two-wheeled trailer drawn by a motorcar and equipped with automatic brakes which are self-applied when the trailer overruns the car and, in the case of a tractor which is drawing a closed trailer especially constructed and used for carryiug meat between the docks and railway station or between wholesale markets and the various rail centres. Nor is an extra man necessary in the case of a trailer vehicle used for the cleansing and maintenance of roads. In all these cases, however, the driver must be able to apply the brakes of the trailer as well as those of the motor vehicle.

No motor vehicle the length crP which exceeds 26 ft. may draw a trailer, and the total laden weight of the two vehicles must not exceed 22 tons.

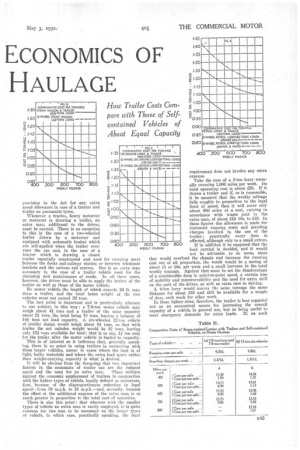

The last point is important and is particularly relevant to our subject, in this way : a 7-8-ton motor vehicle may weigh about 44 tons and a trailer of the same capacity about 2+ tons, the total being 7+ tons, leaving a balance of 14* tons net load capacity. A six-wheeled 12-ton vehicle of similar design would weigh about 6+ tons, so that with trailer the net unladen weight would be 81 tons, leaving only 13+ tons available for load ; that is to say, 1+ ton only for the trailer after the motor vehicle is loaded to capacity. This is of interest as it indicates that, generally speaking, there is no point in using trailers in connection with these larger vehicles, except in cases where the load is of l)ght, bulky materials and where the extra load space rather than weight-carrying capacity is what is desired. It will be obvious from the foregoing that two important factors in the economies of trailer use are the reduced speed and the need for an extra man. These militate against the economic employment of trailers in conjunction with the lighter types of vehicle, legally defined as motorcars, first, because of the disproportionate reduction in legal speed-from 30 m.p.h. to 16 m.p.h.-and, secondly. because the effect ot the additional expense of the extra man is so much greater in proportion to the total cost of operation.

There is also this point : that whereas with the smaller types of Vehicle an extra man is rarely employed, it is quite common for two men to be necessary on the larger types of vehicle, in which case, practically speaking, the legal requirement does not involve any extra expense. Take the ease of a 2-ton lorry normally covering 1,000 miles per week. Its total operating cost is about £20. If it draws a trailer and if, as is reasonable, it be assumed that the weekly mileage falls roughly in proportion to the legal limit of speed, then it will cover only about 600 miles at a cost, varying in accordance with wages paid to the extra man, of about £18 10s. to £19. In these figures due allowance is made for increased running costs and standing charges involved in the use of the trailer : practically every item is affected, although only to a small extent. 800 If in addition it be supposed that the load carried is doubled, and it would

not be advisable to do more, since that would overload the chassis and increase the running cost out of all proportion, the result would be a saying of about £1 or b'Os. per week and a small increase in the total weekly tonnage. Against that must be set the disadvantage of a considerable drop ie point-to-point speed, a certain loss of mobility and manoeuvrability and the need for extra skill on the part of the driver, as well as extra care in driving.

A 4-ton lorry would convey the same tonnage the same distance for about £19 and still be available for a couple of days each week for other work.

In these lighter sizes, therefore, the trailer is best regarded not as an economical means for increasing the overall capacity of a vehicle in general use, but as being useful to meet emergency demands for extra loads. If, on such

occasions, an "odd job" man is available to act as mate, a trailer certainly earns its keep.

The use of light two-wheeled trailers in connection with lorries of 2-ton capacity and thereabouts, engaged in the carriage of light bulky goods, is well worth coasideration, especially where the product, to he carried is such that even the use of specially large-bodied six7wheelers does not enable the full load capacity of the chassis to be utilized. Such a trailer ,would hardly add 5, per cent, to the total cost of operation of the vehicle, but might very well increase its carrying capacity by 50 per cent. or 60 per cent.

For this use the most popular type of vehicle is that having a capacity of seven to eight tons operating in conjunction with a trailer of light capacity. Generally, the total load which can be carried, while still keeping within the legal limit of 22 tons, is 141 tons. Where loads of that size are regularly available then conditions of use will determine whether it is better to employ a vehicle and trailer or a 12-ton rigid-type six-wheeler.

The accompanying tables are of interest as indicating the comparative merits of these two methods of transport. Figures are _given for petrol-e-ngined vehicles, oil-engined vehicles and steam wagans. They show that, up to mileages within the capacity of a lorry and trailer, assuming a 48hour week, the self-contained vehicle is lower in cost per mile but more expensive in cost per ton-mile. To assess the latter figure I have assumed that the vehicle travels consistently fully loaded.

It is, as I have stated, the conditions of use rather than the actual cost which determine the choice, and in this con nection the length of a day's haul may often be the deciding factor. If, for example, the extra speed of the 12-tonner would enable it to do certain routine journeys within a working day whereas a vehicle and trailer could not get home the same night, then it would probably be preferable to use the former.

In a rough explanation of this hypothesis it may be useful to indicate limiting mileages. A lorry and trailer travelling, say, six hours in a day cannot be expected to cover more than SO to 90 miles, which puts the limit on its radius of operation at about 40 to 45 miles. A self-contained 12-tonner in similar circumstances could cover about 120 miles, thus increasing the radius of operation to 60 miles. (I have allowed a greater proportionate average speed to the self-contained vehicle.) The same argument might be extended in cases where it is preferable to ensure the completion of a round journey inside two days. For that the limits of radius of operation are from 100 to 110 miles for the lorry and trailer and about 150 for the single vehicle.

For use with the smaller types of industrial tractor a trailer is particularly well adapted for work over distances which ,enable one tractor to be used in conjunction with three trailers of which one is being loaded, one unloaded and the other travelling.

In conclusion reference must be made to a particular type of trailer-hauling unit, the Beardmore Multi-wheeler which, I understand, is classed under the Road Traffic Act as a load-carrying vehicle drawing a trailer, and has a legal speed limit of 16 M.p.h., carrying 15 tons.