THE LONDON TRAFFIC SCHEME

Page 118

Page 119

Page 120

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By John Darker,

AMBIM

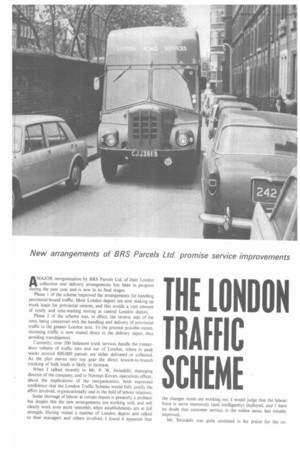

AMAJOR reorganization by BRS Parcels Ltd. of their London collection and delivery arrangements has been in progress during the past year and is now in its final stages.

Phase 1 of the scheme improved the arrangements for handling provincial-bound traffic. Most London depots are now making up trunk loads for provincial centres, and this avoids a vast amount of costly and time-wasting sorting at central London depots.

Phase 2 of the scheme was, in effect, the reverse side of the coin, being concerned with the handling and delivery of provincial traffic in the greater London area. To the greatest possible extent. incoming traffic is now routed direct to the delivery depot. thus avoiding transhipment.

Currently. over 200 balanced trunk services handle the tremendous volume of traffic into and out of London, where in peak weeks around 800,000 parcels are either delivered or collected. As the plan moves into top gear the direct branch-to-branch trunking of bulk loads is likely to increase.

When I talked recently to Mr. P. W. Swindells, managing director of the company, and to Norman Kevan, operations officer, about the implications of the reorganization, both expressed confidence that the London Traffic Scheme would fully justify the effort involved, organizationally and in the field of labour relations.

Some shortage of labour at certain depots is presently a problem but despite this the new arrangements are working well, and will clearly work even more smoothly when establishments are at full strength. Having visited a number of London depots and talked to their managers and others involved, I found it apparent that the changes made are working out. I would judge that the labour force is more intensively (and intelligently) deployed, and I have no doubt that customer service, in the widest sense, has notably improved.

Mr. Swindells was quite unstinted in his praise for the .co

ration of the trade unions, at all levels, in working out the ty radical alterations in duties and responsibilities. The senior le union officers in the London area had backed the scheme de-heartedly from the start. "Without their backing". Mr. ndells told me, we should not have got very far. Without r persuasive support in the past 12 months this necessary -ganization could not have been put through".

a time when trade unions and trade unionists sometimes )y an indifferent Press, I think it is right that this aspect should given the prominence it deserves in this encouraging story of' lagement enterprise.

he London Traffic Scheme reorganization had its origin in conviction of top management that only a drastic reshaping the existing traffic pattern could effectively resolve the imtsely costly (and publicly embarrassing) problem of seasonal k traffic flows. The management's determination to make radical nges was not purely subjective. It was strengthened by the fence of wide dissatisfaction with the standard of service vided to customers.

or some time the company have subjected themselves to a Tic movement "audit", random tests of service standards in -Won and elsewhere revealing points of weakness in the ;anization. A schedule of Booked Transit Times shows the

normal transit time between various areas, and it is against this norm that delays are judged.

Parcels traffic peaks are a well-known phenomenon in transport. The worst, in the autumn, arises almost overnight, and though the date of its onset is broadly known it is not possible to forecast D-day with precision nor, at the start of the rush, to guess its extent or duration. The volume of parcels handled in the autumnal peak is considerably greater than the spring peaks, but the lesser peaks present the same kind of problem.

If London parcels traffic presents a complex problem to management, the front-line troops—the drivers—face daily difficulties with cheerfulness and resource. The increasing intensity of road traffic provides a constant challenge, but the physical reconstruction of large areas in central London, with the accelerating trend towards multi-storey buildings, adds to the drivers' difficulties. And the time available in which to carry out their work is compressed by parking restrictions, traffic congestion and shorter shop opening hours, into appreciably fewer hours than formerly.

London's uniqueness in the context of parcels traffics lies in the major part it plays in the commerce of the country as a whole. With BRS Parcels Ltd. roughly one third of all parcels traffic originates from, or is consigned to, or must pass through the

Greater London complex. Small wonder that when London parcels depots have been -over the top" in recent years the whole country has been aware of it. Delayed parcels have a snowball effect; serious hold-ups in any part of the system affect every other part progressively and cumulatively.

The London Traffic Scheme is based on a reallocation of the total volume of work done by four central and nine suburban depots. The new catchment areas are largely based on postal district numbers, and the general effect has been to concentrate the area served by each depot. particularly in the central London area. For example, City Branch at Macclesfield Road, the largest depot of its kind in Europe, with a daily throughput of around 30,000 parcels, is now wholly responsible for City and West End collections and deliveries including postal districts EC 1 to 4, WC1 and 2, W9 and NI, as compared with its previous and overlapping coverage of s more dispersed area.

Rounds much more compact

Central area drivers' rounds are now very much more compact and, typically, cover six to eight main streets with their adjacent "turnings", though some drivers serve many more streets and others as few as one or two. The contraction of the area served by each driver enables each man to make himself a specialist in meeting the requirements of each customer in his district. It needs a high order of intelligence to serve the varied, and varying, demands of a group of diverse customers in present-day conditions, and drivers develop a flair for this arduous work. I was interested to learn from Norman Kevan that new recruits learn their rounds (and their vitally important documentary procedures) at the hands of experienced drivers; the time spent under training is, I have no doubt, very well worth while.

Macclesfield Road's imperturbable manager, Bert Harvey, expressed himself to be well satisfied with the London Traffic Scheme. "My drivers are far more happy than they used to be", he told me. "They study their customers' needs individually, the new arrangements have speeded up operations, and a better service is being provided."

When I visited Macclesfield Road one morning recently, many trunk vehicles were well on the way to being loaded. The parcels had been collected before 11 a.m.—after the drivers had delivered their loads, and a high proportion would be delivered within 24 hours of collection. Apart from the convenience of the early collection to customers, the steady flow of inwards parcels throughout the day greatly helps to maintain the productivity of the platform staff. The outer suburban depots, of course, cover a much wider area —though here, again, the postal area is mainly used as the basis of the driver's round. At Tottenham, a typical medium sized suburban depot. manager Bill Hewitt told me what a great operational.convenience this has proved. Some of his drivers cover two postal districts, and any queries concerning traffic to or from those areas can be quickly referred to the driver concerned.

Not all Tottenham drivers serve such relatively compact areas, for the depot's collection and delivery radius extends north through Potters Bar to Hertford—an area with a substantial "green fields" element.

Tottenham's average throughput is rather more than 10,000 packages a day, excluding a good deal of specialized traffic, and this compares with the smallest of the outer suburban depots, High Wycombe, which handles some 2,000 packages daily.

Altogether the London depots of BRS Parcels Ltd. collect or deliver 150,000 parcels a day and, in all the circumstances, it is commendable that the vast majority are delivered within the scheduled delivery time. The company is in no way complacent about any traffic that is delayed in transit, whatever the reason. Collecting as they do some 100 million parcels annually and with a fluctuating demand according to seasonal and other circumstances, the correct routing of packages over the 9,000 routes throughout the country over which the company works is of the utmost importance. Routing test checks are carried on continuously but many delays and non-deliveries occur because of inadequate addressing and the use of insecure labels. The company issues a leaflet "Package Protection" giving advice on procedure to minimize the risk of loss and damage in transit,

Local joint committees

I referred earlier to the co-operation of the trade unions in launching this ambitious scheme. The larger central London depots all have their own local joint committees and these have fully discussed and will continue to discuss the detailed working of the scheme and any necessary adjustments that may be called for. The outer suburban depots liaise staff-wise via a special LJC which meets monthly at Shoreditch Town Hall.

The new London parcels manager. Mr. S. C.-G. White, takes over his exacting task at an appropriate moment and all concerned with the smooth functioning of the national parcels service will wish him well. The troublesome -peaks" must still be coped with, but the machine is now in better shape to deal with them.