SILENT SPEEDY, SAFE

Page 64

Page 65

Page 66

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

HAVING travelled some 3,400 miles in a Thames-Duple coach during the record breaking London-Moscow run last year, I can claim to be reasonably well acquainted with the potentialities of this design, particularly for fast long-distance touring.

It was refreshing, nevertheless, to have an almost identical example to myself for two days, so that I could carry out a normal road test along the lines more usually adopted by The Commercial Motor. The results

obtained backed up my original impressions of this vehicle, in that, for a medium-priced 41-seat coach, it oilers the ability to cover the ground with surprising rapidity, but without exorbitant fuel costs and with a general degree of comfort and silence which is totally unexpected.

The coach employed for the Russian journey had a basically similar chassis to that offered to me for test. The standard rear springs had, however, been replaced by heavy-duty exporttype units, and the long-distance vehicle had four of the standard 28gal, fuel tanks. The engine was similar—the Ford 6D 100 b.h.p. (net) off engine—and my test vehicle had— like the outfit that went to Russia— an Eaton two-speed axle affording ratios of 4.5 and 6.25 to 1.

The chassis specification is generally straightforward and many 'names Trader goods-chassis components are used. Only one wheelbase is offered —17 ft. 8 in.—and the gross weight rating is 8+ tons. The frame has fiat topped side members and six riveted cross members. The semi elliptic springs, which are 45 in. long aL the front and 5 ft. long at the rear, are controlled by lever-type dampers.

Driving control layout differs slightly from that of the Trader models, in that the pedals and steering column are set farther forward in relation to the engine and gearbox. This allows flush-fronted body styling to be adopted without the driver being too far back from the windscreen, but it has the slight disadvantage that the gear lever is a little too far behind the driver for comfort.

As an optional extra, hydraulic steering-servo equipment can befitted. but as the steering never becomes heavy, it is unlikely that operators will think it is necessary.

Where the Thames passenger model differs most from the Trader is in respect of the braking. The heavier goods vehicles tend to be under braked, because of the use of rather small areas, but the passenger chassis has really adequate braking, with 16-in. by 3-in, front brakes and 15.25-in. by 5-in, rear units.

These give a total frictional area of 480 sq. in., corn oared with an area of 436 sq. in. for the Trader 7-tortner, which can operate at up to 2 tons higher gross weight. One cannot but help hoping that the passenger-vehicle brakes will eventually be adopted for the goods models.

The Duple body of the test coach carried the type name Yeoman, and differed only slightly from the. 1959

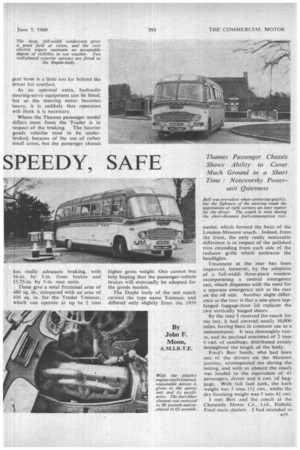

Roll was prevalent when cornering quickly, but the lightness of the steering made the negotiation of tight corners an easy matter for the driver. The coach is seen during the short-distance fuel-consumption test.

model, which formed the basis of the London-Moscow coach. Indeed, from the front, the only really noticeable • difference is in respect of the polished trim extending from each side of the radiator grille which embraces the headlights.

Treatment at the rear has been improved, however, by the adoption of a full-width three-piece window incorporating a central emergency exit, which dispenses with the need for a separate emergency exit at the rear

on the off side. Another slight difference at the rear is that a one-piece top

hinged luggage-boot lid replaces the two vertically hinged doors.

By the time 1 received the coach for my test, it had covered. nearly 10,400 miles, having been in Constant use as a

demonstrator. It was thoroughly runin., and its payload consisted of 2 tons 6 cwt. of sandbags, distributed evenly

throughout the length of the body.

" Ford's Bert Smith, who had been one of the drivers on the Moscow, journey, accompanied me 'during the testing, and with us aboard the coach was loaded to the equivalent of 41 passengers, driver and 6 cwt. of baggage. With full fueltank, the kerb weight was 5 tons 111 cwt., whilst the

dry licensing weight was 5 tons 41 cwt. I met Bert andthe coach at the

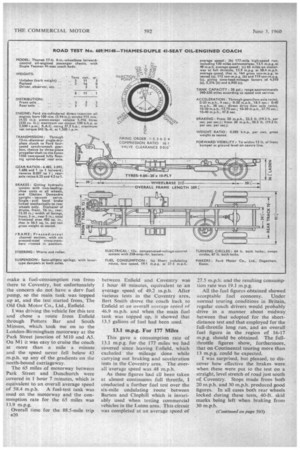

Chaseside Motor Co., Ltd., Enfield, Ford main dealers. I had intended to make a fuel-consumption run from there to Coventry, but unfortunately the concern do not have a dery fuel pump, so the main tank was topped up at, and the test started from, The Old Oak Motor Co., Ltd., Enfield.

I was driving the vehicle for this test and chose a route from Enfield through Potters Bar and South Mimms, which took me on to the London-Birmingham motorway at the Park Street junction of M10 and A.5. On M1 it was easy to cruise the coach at more than a mile a minute and the speed never fell below 43 m.p.h. up any of the gradients on the north-bound carriageway.

The 65 miles of motorway between Park Street and Dunchurch were covered in 1 hour 7 minutes, which is equivalent to an overall average speed of 58.4 m.p.h. A fuel-test tank was used on the motorway and the consumption rate for the 65 miles was 13.9 m.p.g.

Overall time for the 88.5-mile trip 810 between Enfield and Coventry was 1 hour 48 minutes, equivalent to an average speed of 49.2 m.p.h. After various tests in the Coventry area, Bert Smith drove the coach back to Enfield at an overall average speed 01 46.9 m.p.h. and when the main fuel tank was topped up, it showed that 13.5 gallons of fuel had been used.

13.1 m.p.g. For 177 Miles

This gave a consumption rate of 13.1 m.p.g. for the 177 miles we had covered since leaving Enfield, which excluded the mileage done while carrying out braking and acceleration tests in the Coventry area. The overall average speed was 48 m.p.h.

As these figures had all been taken at almost continuous full throttle, I conducted a further fuel test over the six-mile undulating route between Barton and Clophill which is invariably used when testing commercial vehicles in the Luton area. This circuit was completed at an average speed of 27.5 m.p.h. and the resulting consumption rate was 19.1 m.p.g.

All the fuel figures obtained showed acceptable fuel economy. Under normal touring conditions in Britain, regular coach drivers would probably drive in a manner about midway between that adopted for the shortdistance test and that employed for the full-throttle long run, and an overall fuel figure in the region of 16-17 m.p.g. should be obtained. The fullthrottle figures show, furthermore, that on Continental touring more than 13 m.p.g. could be expected.

I was surprised, but pleased, to discover how effective the brakes were when these were put to the test on a straight, level stretch of road just south of Coventry. Stops made from both 20 m.p.h. and 30 m.p.h. produced good figures. In all cases both rear wheels locked during these tests, 40-ft. skid marks being left when braking from 30 m.p.h.