A FREE HAND With th FREELINE

Page 50

Page 51

Page 52

Page 55

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

The Latest Daimler Freeline Passenger Chassis fir Export Puts Up a Fine Performance at of tons Gross Weight : Powered COntrols Reduce Fatigue and Speed Up

Running Schedules John F. Moon,

A.M.I.R.T.E., Gets WHEN the latest Daimler Freeline export passenger chassis was shown at the Commercial Motor Show last yeac it was offered with a 20-ft. 4-in, wheelbase and an almost infinitely variable specification to suit it for hard service in all parts of the world. The chassis also incorporated several modifications to increase longevity, and after two days of arduous testing with one of these chassis I am able to testify to the high standard of its performance under difficult conditions.

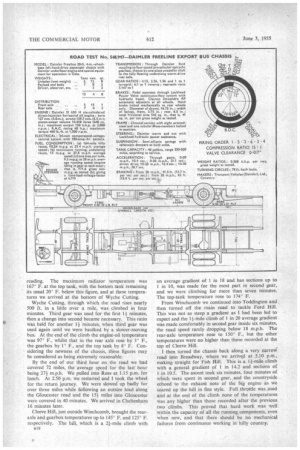

The highlight of the test was a 164-mile run through the Malvern and Cotswold Hills, during which the chassis, running at nearly 131 tons gross weight, returned a fuel-consumption rate of 10.24 m.p.g. at an average speed of 23-4 m.p.h. Taking a 36-ft.-Iong, 8-ft.-wide chassis through this part of the country at such an average speed speaks well for its manceuvrability, acceleration and climbing power.

The left-hand-drive test chassis was one of 16 ordered by Schoyens Bilcentraler A.S., of Oslo, to be supplied through the Daimler distributors, Rutebileiernes Standardiserings A.S. Schoyens Bilcentraler already operate 15 Freeline and six CD.650 chassis, and the present batch of Freelines incorporates several modifications specified after experience with such vehicles in a climate which ranges from temperate to arctic.

Daimler Oil Engine

A Daimler D 650 H horizontal oil engine, rated at 150 b.h.p., a four-speed pre-selector gearbox and -5.167 to 1 rear axle were in the standard specification. Extras included snow shields round the exhaust pipe, the radiator and the fan drive; specially strengthened and lengthened drop frame extension for the rear entrance. which has to accommodate 16 standing passengers, and a dropped section at the front of the right-hand side member to allow" for the front-entrance steps.

Spare fan and dynamo belts were attached to their respective drive covers to enable belts to be changed without disconnecting. the drive shafts; a puller-type radiator fan and home-market radiator had been specified because air is to be drawn through the radiator stack for body heating, and the mechanical gear change had a hydraulic servo to reduce the pedal pressure.

a16 Sine the Freeline was last tested by The Commercial Motor, various modifications have been made to the standard specification. The Lockheed seven-cylindered radial hydraulic pump is now positively driven from the engine timing train, instead of being driven in tandem with the radiator fan, and the fan drive has three V-belts

to reduce the risk of breakages.

A modified sump breather, incorporating a gauze filter element, has been adopted to improve the engine breathing, and bellows-type face seals are used at the fluid coupling and the front of the rear-axle wormshaft. These seals are claimed not to need replacement between overhauls of the major units.

A gear-type lubricating pump is incorporated in all current Daimler pre-selector gearboxes to provide a positive feed to the gear trains at all speeds. This feed increases with the engine speed and the circuit includes a pressure-relief valve, set to blow off at 30 p.s.i.

Other modifications concern the rear suspension, the front hanger brackets of which have been increased in depth to allow less-cambered springs to be used, with a subsequent improvement in spring life and in travelling

for the gross weight of 13 tons 4.cwt. The chassis was new, having come off the assembly line only a few days previously, and was stiff mechanically.

Within half an hour of starting from the works we had made a brisk run into Kenilworth, with Alan Watts, of the design department, driving. At this point the radiator topand bottom-tank temperatures had reached 155' F. and 135' F. respectively. These proved to be their normal operating temperatures throughout the day, the average ambient temperature being 53° F.

In Kenilworth there were several delays because of the inability of some drivers to realize the size of our vehicle. The Kenilworth-Warwick road, being narrow and busy, also caused a reduction in speed. After crawling through Warwick we made good time to Stratford-on-Avon, and entered the town at 11.10 a.m., an hour after starting, having covered 20 miles.

Worcester was reached at noon. We managed to put 244-miles into the second hour of running, and by then the gearboxthermometer was registering 91' F., the other temperatures remaining unchanged. The engineoil temperature was still below 90° F., because of the exposed position of the unit. We then began the long climb up 300 ft. through Malvern Link into Great Malvern.

At 12.30 p.m., after a 11-mile, five-minute climb, we entered Great Malvern; the rear-axle temperature had risen to 140° F., with a 9° F. rise in the gearbox a17 reading. The maximum radiator temperature was 167° F. at the top tank, with, the bottom tank remaining its usual 20° F. below this figure, and at these temperatures we arrived at the bottom of Wyche Cutting.

Wyche Cutting, through which the road rises nearly 500 ft. in a little over a mile, was climbed in four minutes. Third gear was used for the first If minutes, then a change into second became necessary. This ratio was held for another 11 minutes, when third gear was used again until we were baulked by a slower-moving bus. At the end of the climb the engine-oil temperature was 97° F., whilst that in the rear axle rose by 3° F., the gearbox by 1° F., and the top tank by 8° F. Considering the newness of the chassis, these figures may be considered as being extremely reasonable.

By the end of our third hour on the road we had covered 72 miles, the average speed for the last' hour being 27f m.p.h. We pulled into Ross at 1.15 p.m. for lunch. At 2_50 p.m. we restarted and I took the wheel for the return journey. We were slowed up badly for over three miles while following an outsize load along the Gloucester road and the 151 miles into Gloucester were covered in 40 minutes. We arrived in Cheltenham 16 minutes later.

Cleeve Hill, just outside Winchcomb, brought the rearaxle and gearbox temperatures up to 145° F. and 125° F. respectively. The hill, which is a 21-mi1e climb with B18 an average gradient of 1 in 18 and has sections up to 1 in 10, was made for the most part in second gear, and we were climbing for more than seven minutes. The top-tank temperature rose to 174° F.

From Winchcomb we continued into Toddington and then turned off the main road to tackle Ford Hill. This was not as steep a gradient as I had been Ted to expect and the II-mile climb of 1 in 20 average gradient was made comfortably in second gear inside six minutes, the road speed rarely dropping below 18 m.p.h. The rear-axle temperature rose to 150° F., but the other temperatures were no higher than those recorded at the top of Cleeve Hill.

I then turned the chassis back along a very narrowi road into Broadway, where we arrived at 5.10 p.m., making straight for Fish Hill. This is a 11-mile climb with a general gradient of 1 in 14.2 and sections of 1 in 10.5. The ascent took six minutes, four minutes of which were spent in second gear, and the countryside . echoed to the exhaust note of the big engine is we soared up the hill in fine style. Full throttle was used and at the end of the climb none of the temperatures was any higher than those recorded after the previous two climbs. This proved that hard work was well within the capacity of all the running. components, even when new, and that there should be no mechanical failures from continuous working in hilly country. Three hours after leaving Ross we reached Stratford again, having covered the 69 miles from Ross at an average speed-of 23 m.p.h. The final 22 miles back to the Daimler works were covered without incident in 55 minutes and topping-up the fuel tank at the end of the run required 16 gallons.

After four hours at the wheel I was not in any way tired and would willingly have started out again on a similar trip. The power-assisted steering, where much of the credit for the effortless control of the chassis lay, has a high enough r'atio to enable road " feel " to be retained without transference of shocks to the wheel, and yet the ratio is not so high as to make low-speed manceuvring hard work.

Suspension of the chassis was excellent and in our position ahead of the front axle no liounee, pitch or sway were discernible when travelling over anything like reasonable road surfaces.

The brakes were smooth, progressive and powerful.

and, although they were not fully bedded-in, no serious fade was experienced during the whole run, despite the fact that all descents were made in top gear with the brakes applied.

Acceleration and braking tests were made along a quiet road near Baginton, on the outskirts of Coventry, and served to verify impressions obtained during the previous day. The engine has a good. torque curve which is almost flat between 800 r.p.m. and 1,200 r.p.m.

Three braking tests were made from each speed and the relative distances were within a foot of each other on each occasion. A good pull on the hand brake at 20 m.p.h. produced a Tapley meter reading of 20 per cent: At all times neutral was engaged before applying the brakes. As an alternative to the Lockheed equipment, the chassis can now be supplied with BendixWestinghouse air brakes, made in this country by the Clayton Dewandre Co., Ltd.

Extensive fuel-consumption tests were carried, out along the Coventry by-pass, a two-gallon test tank having been rigged up for this purpose. A 4.05-mile return route between two roundabouts was chosen and this undulating section was used twice for each test.

The first test was a non-stop run, during which the speed was not allowed to exceed 35 m.p.h. The circuit was covered in 17f minutes and five pints of fuel were used, giving a consumption rate of 13 m.p.g. at an average speed of 27.5 m.p.h. The resulting time-loadmileage factor of 4,719 shows good economy in view of the high loading and average speed.

I made no attempt to conserve fuel during the stopsper-mile tests and used. maximum acceleration and braking at each stop. Contrary to good practice, but

still a trick of many drivers, I engaged low gear as soon as the chassis had come to rest, and let the engine idle against the flywheel drag during every 15-sec. hall, which has the effect of increasing the fuel-:consumption rate.

As the chassis is intended for use around the suburbs of Oslo, the one-stop-per-mile figure of 9.5 m.p.g. should approximate to the average consumption rate to be expected in service. The average speed of 28 m.p.h. shows, however, that I completed the course in less time than during the non-stop test by using full throttle when accelerating and taking the speed up to 45 m.p.h. between stops. It is possible, therefore, that at least 10 m.p.g. will be returned under similar service conditions, provided that the drivers are conscientious.

At the end of the one-stop-per-mile test, an emergency halt was made from 30 m.p.h. and this produced a Tapley meter deceleration reading of 52 per cent., which, in view of the heavy braking at each stop, compares favourably with the " cold-drums " figure of 70 per cent.

recorded earlier in the day.

The Freeline has been designed to give a high mileage between overhauls ,and to make maintenance, when necessary, an easy task. Brake adjustment, for instance, is unnecessary, because of the Clayton Dewandre R.P. automatic adjusters.

and the Clayton Dewandre 24-point automatic lubricator reduces the number of manual greasing points to 28. These are mainly round the steering, control linkages and propeller shafts and took 9k minutes to charge with a pump grease gun. Topping-up the engine sump took 11 minutes, and to check the gearbox and rear-axle oil levels through the combined level and filter plugs took 1k minutes and 3 minutes respectively. All these and the following tasks were done from underneath or alongside the chassis to simulate as far as possible maintenance conditions with a body in place.

I changed one injector and experienced a little trouble in freeing the dribble return pipe. ' Removal took 4f minutes and replacement occupied 31 minutes. A special box spanner is provided for the injector clamp units to avoid overtightening the nuts and thus damaging the copper sealing washer.

The two, tappet covers took 11 minutes to remove, a tray being placed under the engine to catch the oil, which had not drained back from the heads. A Daimler fitter and his mate adjusted the tappets for me in 12 minutes, each tappet being checked with the cam 180' past the fully open position. I spent 31 minutes replacing the covers and checking the seals for oil-tightness.

AF.other engine task was to change the large full-flow filter element. Six self-locking nuts secure the filter end plate, and when the plate was removed about 1-gal. of oil gushed from the body of the filter. Removal of the element took 4f minutes and a further 4 minutes were spent in replacement, topping up the sump and checking for leaks. Oiling the sump breather took one minute.