iillY TT ER

Page 32

Page 34

Page 36

Page 37

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

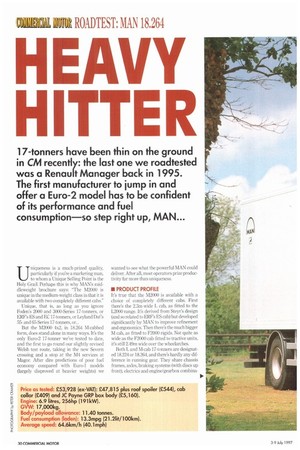

17-tonners have been thin on the ground in CM recently: the last one we roadtested was a Renault Manager back in 1995. The first manufacturer to jump in and offer a Euro-2 model has to be confident of its performance and fuel consumption so step right up, MAN...

Uniqueness is a much-prized quality, particularly if you're a marketing man, to whom a Unique Selling Point is the Holy Grail. Perhaps this is why MAN's middleweight brochure says: "The M2000 is unique in the medium-weight class in that it is available with two completely different cabs."

Unique, that is, as long as you ignore Foden's 2000 and 3000-Series 17-tonners, or ERF's ES and EC 17-tormers, or Leyland Daf 's 55and 65-Series 17-tonners, or...

But the M2000 4x2, in 18.264 M-cabbed form, does stand alone in many ways. It's the only Euro-2 17-tonner we've tested to date, and the first to go round our slightly revised Welsh test route, taking in the new Severn crossing and a stop at the M4 services at Magor. After dire predictions of poor fuel economy compared with Euro-1 models (largely disproved at heavier weights) we wanted to see what the powerful MAN could deliver. After all, most operators prize productivity far more than uniqueness.

• PRODUCT PROFILE

It's true that the M2000 is available with a choice of completely different cabs. First there's the 2.3m-wide L cab, as fitted to the L2000 range. It's derived from Steyr's design (and so related to ERF's FS cab) but developed significantly by MAN to improve refinement and ergonomics. Then there's the niuch bigger M cab, as fitted to F2000 rigids. Not quite as wide as the F2000 cab fitted to tractive units, it's still 2.49m wide over the wheelarches.

Both L and M-cab 17-tonners are designated 18224 or 18.264, and there's hardly any difference in running gear. They share chassis frames, axles, braking systems (with discs up front), electrics and engine/gearbox combina • tions. The range of available wheelbases is slightly different (see table, right).

Compare like with like, and you find that the L-cab version weighs 125kg less than its M cab equivalent---less of a difference than you might expect, but explained by the more modern basic design of the M cab. In either case, the 18.224 is 50kg lighter than its more powerful brother.

Spec-spotters will notice that the distance from the centreline of the front axle to the foremost body position is 545mm for the L day cab, and just 375mm for the M cab, which has a much greater front overhang. This situation is reversed for L and M sleeper cabs, where the dimensions are 775mm and 811mm. The much bigger M sleeper weighs 95kg more than the day cab, whereas the L sleeper is only 60kg heavier than its day cab counterpart.

The "224" engine is actually rated at 217hp, and has mechanically controlled fuel injection, while the 256hp "264" is fitted with EDC electronic control.

It puts out 18% more peak power than the 224 at marginally lower revs, and 21% more torque across the same range.

The power-to-weight ratio is pretty impressive at around 15hp/tonne, which equates to a 7.5-tonner rated at 113hp. But in an era of 600hp 40-tanners the 18.264 hardly looks extravagant, and a host of recent test vehicles has proved that high power need not mean high fuel consumption. This has a lot to do with the fat torque curves typical of elec tmnic engine control—and using the appropriate driving technique. For a Euro-2 engine this generally means letting the torque do the work, without resorting to high revs except on punishing hills.

As with many model ranges, the M2000 matches high-power engines with multi-speed gearboxes: the 18.224 gets a six-speed Eaton 5206, while the 18.264 tested here gets its eight-speed (plus crawler) 8209 counterpart. Why? Surely the less powerful, less torquey engine would benefit more from the extra ratios and the range could be rationalised? Answers on a postcard, please...

The eight-speed box has a direct-drive top gear, and is matched to a 3.70:1 drive axle: the six-speeder (with an overdrive-top ratio of 0.79:1) comes with a 5.29:1 axle. This gives the 18.224 a maximum geared speed of 68mph,

while the 18.264 is geared for 75mph making it a more relaxed drive, while keeping its torque advantage.

MANs generally conform to a cliche about German trucks: they're no lightweights. But there's a good reason for this, quite apart from the family-size cab. On M2000 17-tanners with wheelbases of 5.50m or more the bolted-and I. cab M cab Wheelbase options I. cab M cab riveted frame is a 70x210mm channel in 8mmthick steel—dimensions which wouldn't shame a 6x4 tipper chassis—so it's not surprising if the body/payload allowance is unimpressive. Shorter chassis make do with a 7mm-thick frame.

Our test vehicle wore MAN's own roof spoiler and cab collar, and a neatly finished JC Payne body in GRP with aluminium posts and rails. It looked good, but it lacked side skirts: the record-holder for fuel consumption round our Welsh route was Iveco's 170E23S SuperCargo in Euro-1 form, fitted with a full Ecotek body kit, followed by a similarly equipped Leyland Daf 60210. Could the MAN hold its own?

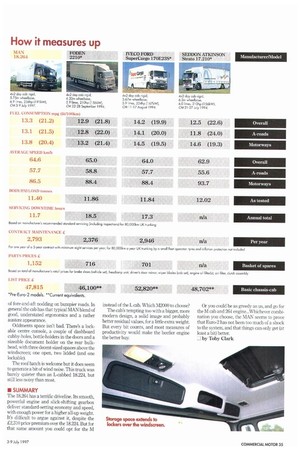

• PRODUCTIVITY Take a note of this figure: 13.3mpg. It's a benchmark against which future 17-tonners will be measured, for a couple of reasons. Primarily, of course, because it's the first Euro-2 model to go round the Welsh route, but I • also because it's a very good figure in any

case. The only other 17-tonners to beat this overall figure have been the super-slippery models from Iveco and Leyland Daf but the Iveco was just 2.36m wide and the Daf was 2.39m wide, while the MAN is also 180mm taller than the Iveco. The Daf (no longer current, of course) wasn't even a Euro-1 model.

The 18.264 returned a good average speed, too: not surprising, given its blistering 080km/h time at MIRA, where it was more than six seconds faster than the nearest contender. Its 48-80km/h time was also the best yet.

The MAN is frugal and fast; its overall productivity is really only harmed by its unladen weight (it gives away 600kg to rivals such as the Cummins-powered Seddon Atkinson Strato). But a vehicle of this size, with this cab, might be best suited to drawbar operation. The engine is offered on 6x2 models at up to 23 tonnes, and should be happy at up to 26 tonnes GTW.

• ON THE ROAD With all that torque on tap it's no surprise that the MAN is a breeze to drive, but the engine is also surprisingly responsive even from low revs, probably because of the wastegateequipped turbocharger. Conversely, the exhaust brake (controlled by a heel-operated button, not set too far back) only has significant effect from 2,000rpm up.

The Eaton gearbox has a very light shift, almost too light at first, when you find yourself fighting the lever or inadvertently switching ranges. It's very much a push-across (rather than slap-across) range-change and a relaxed approach is rewarded by swift shifting. It seems churlish to complain about an eight-speed box, but it could do with a split between 7th and overdrive top on A-roads: 40mph corresponds to 1,175rpm in top (well below the green band, but tempting on a level road) or 1,575rpm in seventh, which is a little too harsh on the ears.

One odd feature of the transmission is the ultra-low 13.21:1 reverse ratio which is even lower than crawl: the six-speed box makes do with a 5.43:1 reverse.

We were a little disappointed by the feel from the brakes. The front disc setup had a rather wooden response, though plenty of stopping power was there if you needed it. Unfortunately, a wet track meant we couldn't measure this subjectively.

The best feature? Probably the straightforward cruise control setup, situated on the right-hand stalk. All too rare on middleweight trucks, this is a boon on the motorway and probably helped fuel consumption on the easier stretches of road.

• CAB COMFORT

In reality the M cab doesn't offer a great deal more useful space than the L version. The massive engine hump robs it of a lot of volume, and makes this strictly a two-seater. But there's headroom aplenty and it feels like a "proper" truck; the three steps up into the cab reinforce this feeling.

The air-suspended seat is OK, but the footwell is surprisingly tight. The cab didn't suffer badly from roll, though there was a bit

of fore-and-aft nodding on bumpier roads. In general the cab has that typical MAN blend of good, understated ergonomics and a rather austere appearance.

Oddments space isn't bad. There's a lockable centre console, a couple of dashboard cubby-holes, bottle-holders in the doors and a sizeable document holder on the rear bulkhead, with three decent-sized spaces above the windscreen; one open, two lidded (and one lockable), The roof hatch is welcome but it does seem to generate a bit of wind noise. This truck was barely quieter than an L-cabbed 18.224, but still less noisy than most.

• SUMMARY The 18.264 has a terrific driveline. Its smooth, powerful engine and slick-shifting gearbox deliver standard-setting economy and speed, with enough power for a higher all-up weight. It's difficult to argue against it, despite the £2,310 price premium over the 18224. But for that same amount you could opt for the M instead of the L cab. Which M2000 to choose?

The cab's tempting too with a bigger, more modern design, a solid image and probably better residual values, for a little extra weight. But every bit counts, and most measures of productivity would make the beefier engine the better buy. Or you could be as greedy as us, and go for the M cab and 264 engine Whichever combination you choose, the MAN seems to prove that Euro-2 has not been too much of a shock to the system, and that things can only get (at least a bit) better.

_1 by Toby Clark