• They planned for the seventies in 1883

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

by J. P. B. Sherriff, MITA

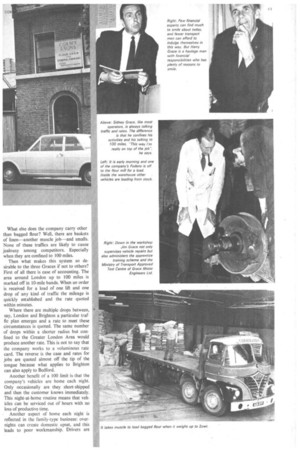

PICTURES BY DICK ROSS OPERATIONS confined to a 100-mile radius may appear to some to be a new transport concept but to one firm at least it is as old as the company. G. Grace and Sons of Deptford, London, SE8, has been in business for years and has still to operate beyond 100 miles in excess of 16 tons gross.

The idea of confining activities to 100 miles has evoked sounds of deep lamentation from many established long-distance men but for the three Graces, Harry, Sid and Jim, it is of no concern. But then they are the grandsons of George who found he could make a living in transport by travelling only a few miles away.

It was an act of good judgment which directed the previous directors, the boys' fathers, to limit their scope because today they are established 100-mile men.

Harry told me that he understood how the established long-distance men felt. "After all, we were lucky that the distance was set at 100 miles." He recalled that I had guessed that the Government limit would be 80 miles. "Where would we have been then?" he quizzed. Well, they might have lost a few customers in the over 16-ton class but only a few; G. Grace and Sons would still be a very worthwhile business because much of its operating is done in less than 80 miles.

As it is, the promised new law won't alter the business and so this long-established company will continue to act as efficiently as it always has done.

It is uncanny how close the company comes to what appears to be a model transport company for the future in terms of

current legislation. The work is functionalized: Harry is the finance man, Sid the operator and Jim the engineer. And while each is an autonomous working unit there is daily consultation to produce the end pro

duct profit.

In a tidy upstairs office Harry and Sid get on with their separate tasks, always aware that the success of the company depends on their efforts to maximize usage of vehicles and minimize cost. Down in the workshop Jim controls the labour time and valuable stocks, conscious that he could sabotage the efforts of the others if he were to permit waste of either. Three directors all capable of holding a transport manager's licence—and all probably will—are each aiming at continued efficiency and moderate expansion within 100 miles.

Just as the three cousins inherited their share of the business from their fathers so will their sons inherit from them. Each boy is following in father's footsteps ready to take over and develop the business to meet the demands of their day. Let there be no mistake, G. Grace and Sons is not available for take-over bids! It's successful and it's family and I understand it intends to remain so.

Sitting on a very sound financial base the company is complying with the first requirement of the Transport Act. It is working well within its capital resources and could well be licensed to operate in excess of the 50 vehicles it employs at the moment.

Nor are there likely to be any objections about the premises the company occupies. There is ample covered and open space for many more vehicles. The repair and maintenance unit has a well-appointed workshop perfectly capable of catering for the needs of today and for many years to come. The stock is worth £12,000.

There is in the Transport Act scope for objection to an operator's licence from prescribed trade unions. Again this company has nothing to fear. Just as the directors are sons of former directors so are drivers sons of former drivers. In the Welsh coalfields it used to be unthinkable that a lad would not follow his dad to the coalface. In Deptford today if your dad drives for Grace then it's likely that you will too; this attitude breeds loyalty. There's a waiting list of drivers' sons who want to go to Croft Street. That is the framework of the company which 85 years ago unconsciously began planning for the 70s.

How does it operate? The basic thinking is this: "If it is within our licence conditions well carry it." This is a trite phrase used too often by some to generate business without the intent. But this firm says it and means it.

For an example we must look at what comprises the bulk of its traffic—bagged flour. This is the day of cartoned goods or bulk delivery, the mechanized era in which machines have replaced muscle. But there are still calls, and many of them, for bagged delivery. These calls cannot be made using mechanical aids—broad shoulders and big biceps are needed: Such physical attributes are not in plentiful supply but down Deptford way there appears to be plenty; certainly G. Grace and Sons has no difficulty in recruiting the right men. What else does the company carry other than bagged flour? Well, there are baskets of linen—another muscle job—and smalls. None of these traffics are likely to cause jealousy among competitors. Especially when they are confined to 100 miles.

Then what makes this system so desirable to the three Graces if not to others? First of all there is ease of accounting. The area around London up to 100 miles is marked off in 10-mile bands. When an order is received for a load of one lift and one drop of any kind of traffic the mileage is quickly established and the rate quoted within minutes.

Where there are multiple drops between, say, London and Brighton a particular traf fic plan emerges and a rate to meet these circumstances is quoted. The same number of drops within a shorter radius but confined to the Greater London Area would produce another rate. This is not to say that the company works to a voluminous rate card. The reverse is the case and rates for jobs are quoted almost off the tip of the tongue because what applies to Brighton can also apply to Bedford.

Another benefit of a 100 limit is that the company's vehicles are home each night. Only occasionally are they short-shipped and then the customer knows immediately, This night-at-home routine means that vehicles can be serviced out of hours with no loss of productive time.

• Another aspect of home each night is reflected in the family-type business: overnights can create domestic upset, and this leads to poor workmanship. Drivers are

used to being at home and there are no complications of overnight expenses being built into the rate. It all makes for ease of Operation.

When a Grace vehicle breaks down on the road, which is seldom, it is not so far away from home that its load cannot be speedily transhipped and delivered the same day and still within the legal limits of hours. This is of course another advantage of the 100-mile radius: a man can still complete journeys inside the reduced working day.

Grace drivers are not unduly concerned about tachographs; they know what the boss expects of them and they think it is fair. Normally a driver will put on two loads on, say, Monday, Wednesday and Friday and on these days he will deliver one. This late loading means that he is last into the garage and all set for a "flyer" in the morning. On Tuesday and Thursday he 'makes two deliveries and loads one. This means that a man should average 16 loads in 10 days. With some spare time built into each schedule drivers can on the odd occasion manage two loads on the one-load day. When this happens the driver is paid a bonus of 5s a ton.

watched two young drivers wash their vehicles and help each other to load from the company's own warehouse in the last hour of the day. Sacks of flour were moved to the lorry by band conveyor and then carried on shoulders along the platform, loaded, and finally sheeted and roped. This was an art which I thought was dying, but I learned it was one on which the Graces were developing their business. An outstanding feature of the company is the esprit de corps which exists. They all acknowledge that there are other good companies; what they refuse to accept is that there are better companies. One man, Alex Nelson, has just completed 47 years' service and he is still driving.

Still moving with the times the company is accepting traffic for areas beyond the magic 100 miles. The goods. are containerized and then delivered to rail sidings for delivery. In this way Grace meets requests from existing customers without breaking its own house rules. In the same way it will allow a driver under pressure from the customer to spend one night away from home if he has multiple drops beyond 45 miles. In these cases the vehicle must be back loaded.

One essential in this type of operation, according to Harry Grace is to have your own warehouse. When vehicles are operating to such a tight schedule delays at collection points can be fatal. Flour represents 50 per cent of Grace's traffic and consequently the firm holds stocks. This means that any delays at the mills need not cause undue worry; loading is performed at Grace's yard. (I am told that delays at the mills do not occur very often.) Not only did George Grace plan his traffic operations for the 70s back in 1883 but it appears he anticipated the Industrial Training Act. Drivers graduate to the wheel through the mate's seat. This develops customer /company relations before the man gets his own vehicle. It also teaches him what the company expects for a day's work, and it produces those biceps 1 mentioned before.

In the workshop Sid has his apprentice training scheme in operation and taking advantage of legislation he is operating an authorized Ministry of Transport Testing Station for private cars and light vans.

The quiet demeanour which sets the Grace cousins apart from many of their contemporaries can be deceptive. They may appear to be living in the past but they are not allowing traffic developments to slip past unnoticed. While 50 per cent of the traffic carried today is the same type of commodity which left Surrey Docks and Silvertown Mill in 1883, new traffics have been generated to meet today's demand. Lyons' London steak houses and tea shops take 125 deliveries each week from three of Grace's vehicles, which are loaded at Lyons' Greenford depot.

Recently the company put a refrigerated lorry on the road. The lorry is divided into two compartments, one to carry food and the other laundry for hotel services.

The Grace fleet is predominantly BMC with a few Foden and Bedford KMs. The company has confined its sub-hiring to six other operators; the thinking here is that the fewer people involved the less chance there is of complications arising.

When will there be another Transport Act to supersede the 1968 legislation? Possibly 25 years hence. That is only a guess but if past events prove anything, watch G. Grace and Sons. This firm's sure to be planning for it now.