WHEN NORMAN HARRIS watches one of his coaches leave on

Page 70

Page 71

Page 72

Page 73

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

tour he doesn't expect to see it again for six months. What's more when he next hears of it, it may be carrying a full load of Buddhist monks on a tour of the monasteries in Nepal.

For when your business is running camping tours from London to Katmandu the unexpected becomes the usual.

Talking to Mr Harris gave me the impression that going to Nepal presented only a few more problems than his fellow operators in Windsor would find running to Clacton. It's not that breakdowns, delays and accidents don't happen —its just that he regards a seized engine inAfghanistan in much the same way as one of his neighbours might think of a puncture in Acton.

Asian Greyhound is the oldest established camping tour operator running to Asia and during this period of time have seen many other firms enter the field only to die away after a few years.

Norman Harris started out in life as a photographer in Australia but wanderlust brought him to Britain and in 1956 he ran his first camping tour to Morocco and Algeria using a Bedford OB coach. But these were very troubled times in North Africa and after several shooting incidents he abandoned this route to go overland to India.

One successful trip was made in the OB but as this was literally falling to bits on returning to England he tried other makes including Guy Vixens and Guy Arabs. These introduced him to Gardner engines which the firm has stuck with ever since. He now owns eight Bristol LS coaches, two Bristol MW's and one Bristol RE. "The Bristols are the closest to the perfect overland vehicle that we can find", Mr Harris told me. "The outward opening door is a bit of a headache, but that's really all".

Mr Harris is a great enthusiast of the Eastern Coach Works bodies fitted to all his vehicles. These have stood up well to the battering of dirt roads. Even after 15 years operating with the National Bus Company in England they can still sur vive three years running to Katmandu before additional strengthening is needed to the roof. Accident damage is very easily repaired on route as it is always very localised. Before the coaches are used on an overland run they are all completely stripped and rebuilt. The body is raised by about five inches to give improved ground clearance, the air intake is repositioned inside the coach to reduce the chance of damage to the engine by dust and sand entering the air intake. Four seats are removed and tables and a public address system put in. Even with this increase in room coaches are as a

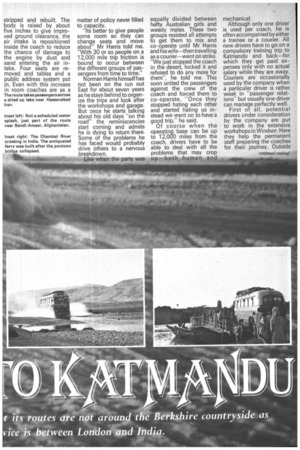

The route takes passengers across a dried up lake near Hassanabad Iran.

matter of policy never filled to capacity. "Its better to give people some room so they can change seats and move about" Mr Harris told me. -With 30 or so people on a 12,000 mile trip friction is bound to occur between the different groups of passengers from time to time." Norman Harris himself has not been on the run out East for about seven years as he stays behind to organize the trips and look after the workshops and garage. But once he starts talking about his old days "on the road" the reminiscencies start coming and admits he is dying to return there. Some of the problems he has faced would probably drive others to a nervous breakdown.

Like when the party was equally divided between hefty Australian girls and weedy males. These two groups resisted all attempts to get them to mix and co-operate until Mr Harris and his wife—then travelling as a courier went on strike. "We just stopped the coach in the desert, locked it and refused to do any more for them", he told me. This soon united the passengers against the crew of the coach and forced them to co-operate. "Once they stopped hating each other and started hating us instead we went on to have a good trip," he said. Of course when the operating base can be up to 12,000 miles from the coach, drivers have to be able to deal with all the problems that may crop up—both human and mechanical.

Although only one driver is used per coach, he is often accompanied by either a trainee or a courier. All new drivers have to go on a compulsory training trip to Katmandu and back—for which they get paid expenses only with no actual salary while they are away. Couriers are occasionally used by the company when a particular driver is rather weak in -passenger relations" but usually one driver can manage perfectly well. First of all, potential drivers under consideration by the company are put to work in the extensive workshops in Windsor. Here they help the permanent staff preparing the coaches for their journey. Outside work is also taken in and Asian Greyhound is prepared to tackle mechanical or body repairs on any sort of vehicle.

The staff trial period enables Mr Harris to have a look at the trainee and see if he is really suitable for the arduous trip ahead of him.

Once out on the road to the Far East it is inevitable that some mechanical problems will crop up. Before it leaves England, the coach will have been completely stripped mechanically—the engine re-ringed—and everything put into top class condition. It will have seven new tyres and a big stack of spares. But despite this, few trips pass without some form of damage either mechanically or bodily. "There's two types of breakdown—the good and the bad," Norman Harris told me. "It does not matter so much what's gone wrong as where its gone wrong." In a pleasant campsite somewhere near civilisation even the most major disaster can be tackled easily. But a breakdown miles from anywhere in the middle of the desert can be murder. Not only is it very difficult to get the parts needed but also there is nothing for the passengers to do until the repair is completed.

On one occasion in the early days of the operation, a coach broke down in the Iranian desert and Norman Harris had to hitch-hike to Tehran to send a cable to Bristol Commercial Vehicles ordering the necessary parts. All would have been well if the Iranian who took the cable had not translated it in Parsi before he sent it. Instead all that happened was that an indecipherable cable arrived at Bristol and Norman Harris was left stranded in the middle of Iran.

He returned to the airport after a week expecting to find the parts but found

nothing. Only after a BOAC captain offered to phone Bristol on his return to England did the parts eventually arrive.

Sometimes breakdowns are due to inferior quality items supplied in the East. Bad oil was the likely cause of two recent engine seizures.

Apart from breakdowns and accidents caused by lunatic eastern drivers the natural hazards of the route would be enough to deter all but the most enthusiastic. Washouts are commonplace on dirt roads, as are drifting sands in the deserts of Pakistan.

Sandstorms are an additional hazard with some so bad as to make any progress at all impossible. On one occasion two coaches stuck in a desert sandstorm were completely stripped of paint — and the glass all became "frosted" by the bombardment of tiny particles.

It's company policy of Asian Greyhound never to give bribes to speed up customs formalities in the East. "The first time you give somebody a bottle of whisky it works a treat," Mr Harris told me, "You can get through the customs posts in hours instead of days. But when you next go through they want a crate of whisky off you instead of just a bottle. Once they know that you don't ever give backhanders then you go through without too much trouble."

Bureaucracy is always making the route out East more difficult. The Asian Greyhound licence takes them from London to Dover and then "on to Katmandu" but strict enforce ment of drivers hours regulations in Germany forced them to miss out this part of the journey to go through France instead. Tachographs cannot stand up to the battering of dirt roads in the East.

The "carnets de passage" demanded by Iran and India would also tie up an enormous amount of cash on deposit in banks if Asian Greyhound did not carry an insurance policy against the cash ever being demanded.

Even in England there are difficulties — especially in getting Certificates of Fitness ssued for the much modified coaches. But Norman Harris is Full of praise for the local staff )f the Department of Transport.

'They have been incredibly lelpful in persuading their leadquarters to give us a iispensation on step-height," le said. "We eventually got this )ecause the vehicles are used

exclusively for overland work,The only unmodified coach is the Bristol RE which is mainly used in this country or for the easier European routes

Although the main roads in Turkey, Iran, India and Pakistan are improving all the time, Norman Harris has no problems in still finding the "out of the way" places to take his passengers.

"Some tour operators stick to the main roads and for all you see you might as well still be on the M2he told me. But Asian Greyhound try to give its customers something special.

Two tours are run, the "Swagman Grand Tourand the "Greyhound Special", which is three weeks shorter. Both tours camp most of the time but the routes do differ. The Grand Tour goes down the Dalmation Coast of Yugoslavia and to Athens while the Special Tour takes the direct route through the centre of Yugoslavia and the northern coast of Greece to Istanbul.

In Iran, the Grand Tour goes south and through the deserts to Pakistan before heading north to Afghanistan and Kabul while the special goes north from Tehran to the Caspian Sea and then through Herat, Kandahar and then Kabul. After Kabul the two tours are identical, both going to Shrinagar, the Tai Mahal, Delhi, Benares and then up to Katmandu in Nepal.

Most of the passengers on Asian Greyhound are en route to Australia and the company can arrange onward travel either direct or via Thailand, Sumatra, and Java. For the 80-day Swagman Grand Tour the cost is £250 while the 59-day Greyhound Special costs £225. This includes the transport cost and the use of tents and cooking equipment. But food, campsite fees etc are not included and Greyhound reckons that these items will cost an additional £30.

When the coaches leave England they have about one ton of food on board and additional supplies are picked up en route.

Selling seats on the Eastbound trips is easier than those of the Westbound, Mr Harris told me. But the shortage of money in England made last year rather a lean one_ The tours are sold through agents such as "Trailfinders" in Kensington and also through advertisements in papers such as "The Times" and "Guardian". The tours seem to attract a very large proportion of doctors and nurses probably as they can find work easily in any part of the world. "It's fine having doctors aboard", Mr Harris told me, "But when one of the other passengers gets ill they can never agree on the treatment."

Seats on trips westbound from Katmandu back to England are harder to sell largely as the cost of travel from Australia is very expensive as there are no cheap flights or discount fares.

Because of the present economic situation, Norman Harris doesn't see much room for expansion in the overland field. Instead he is turning his attention to running camping tours of England — for the English. "It's been tried before without much success" he told me, "but other operators have concentrated on taking incoming tourists around Britain. With the fall in value ef the pound, I think there will be a lot more people staying in England who would be very keen on a family camping tour "