( From the Drawing Boer

Page 50

Page 51

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

by Graham Montgomer e The Engineering Editor describes Fiat's Idromeccanico transmission system as fitted to a conventional single-countershaf gearbox and analyses its advantages for everyday use

IN THE WORLD of engineering, compromise is king, as I have said many times before in "From the Drawing Board." This applies to every form of engineering, be it Cammell Lairds, the Atomic Energy Authority or Leyland Vehicles.

In the transmission field there is no exception to the rule. The higher engine torques being developed by current power units produce higher stress levels in the driveline; the trend towards lower maximum engine speeds while still providing good gradeability and over-theroad speed requires a certain number of steps in the gearbox; the driver now demands a day at the wheel which is less fatiguing. Fair enough.

But at the end of the line, someone has to pay for all this and so the operator has a different list of requirements. He wants — not necessarily in this order — low weight, low cost,. simple construction and a high level of durability and reliability.

So far the driveline which is all things to all men has yet to be invented. In recent years, the advocates of fully and/or semiautomatic transmissions have become more vociferous and to a certain extent they have a point. Yet the fact remains that automatic = complication =cost, Most heavy lorries still employ the classic mechanical method of power transmission which has been used since Roils met Royce, but the limitations ot such a system are well known. The clutch must be of sufficient size to take the torque, sufficient steps must be provided in the gearbox and so on.

Fully automatic gearboxes have been available for some time even for the relatively stringent requirements of the commercial vehicle industry but many of the designs put forward bring their own attendant problems — increased cost and complexity and the lack of the required number of ratios.

The compromise solution put forward by Fiat is that somewhere between the conventional mechanical and the fully automatic transmission there is a hydromechanical transmission — otherwise known to those fluent in Italian as the "Idromeccanico". It consists of a hydraulic unit between the engine and the clutch which can act as a torque converter; as a direct mechanical connection: and as a hydraulic retarder.

A hydraulic coupling, like a torque converter, has advantages such as torque multiplication, cushioning the load on the rest of the drive line and so on. But nothing is ever all advantage and against this must be set the fact that the hydraulic torque converter is not the most efficient of mechanisms.

For this reason most manufacturers incorporate a lock-up clutch to re-establish the mechanical connection as soon as the torque converter has finished its matching role.

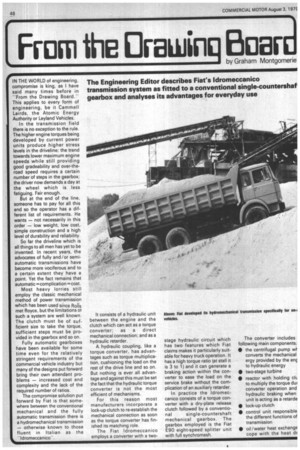

The Fiat ldromeccanico employs a converter with a two

stage hydraulic circuit which has two features which Fiat claims makes it particularly suitable for heavy truck operation. It has a high torque ratio (at stall it is 3 to 1) and it can generate a braking action within the converter to ease the load on the service brake without the complication of an auxiliary retarder.

In practice the Idromeccanico consists of a torque converter with a dry-plate release clutch followed by a conventio nal single-countershaft mechanical gearbox. The gearbox employed is the Fiat E90 eight-speed splitter unit with full synchromesh. The converter includes following main components: • the centrifugal pump wh converts the mechanical orgy provided by the enc to hydraulic energy • two-stage turbine • reactor with holding clu to multiply the torque dui converter operation and hydraulic braking when unit is acting as a retarde • lock-up clutch • control unit responsible the different functions of transmission • oil/water heat exchange cope with the heat d( loped during converter operation and braking.

A servo-operated single dryplate release clutch is fitted to the converter to interrupt the drive — whether hydraulic or mechanical — during gearshifts.

The control unit, or autopilot as it is called by Fiat, consists of a centrifugal regulator, a speed ratio regulator, and a hydraulic valve system. According to the turbine speed and the ratio of turbine to pump speed, the valve system opens or closes the channels to the converter servopistons.

When a gear is engaged (in the high range, as the low is only used for very steep gradients and heavy loads) and the clutch engaged, the vehicle then moves off in hydraulic drive. When a certain speed is reached, the mechanical drive is automatically engaged.

On slowing down, the same procedure happens in reverse. Direct drive is maintained until the speed corresponds to an engine rpm approaching that of maximum torque, at which point the torque converter comes back in.

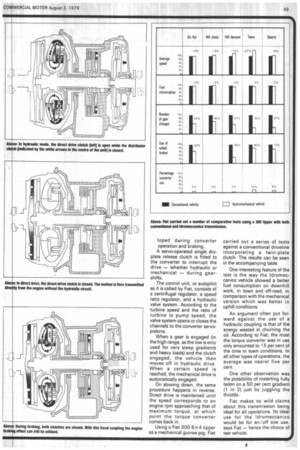

Using a Fiat 300 6x4 tipper as a mechanical guinea pig, Fiat carried out a series of tests against a conventional driveline incorporating a twin-plate clutch. The results can be seen in the accompanying table.

One interesting feature of the test is the way the Idromeccanico vehicle showed a better fuel consumption on downhill work, in town and off-road, in comparison with the mechanical version which was better in uphill conditions.

An argument often put forward against the use of a hydraulic coupling is that of the energy wasted in churning the oil. According to Fiat, the most the torque converter was in use only amounted to 15 per cent of the time in town conditions. In all other types of operations, the average was nearer five per cent..

One other observation was the possibility of restarting fully laden on a 50 per cent gradient (1 in 2) just by juggling the throttle.

Fiat makes no wild claims about this transmission being ideal for all operations. Its ideal use for the ldromeccanico would be for an/off site use, says Fiat — hence the choice of test vehicle.